Without a doubt, the major development of geo-historical impact in 1652 CE was the outbreak of armed conflict between the navies of the two powerful Protestant-European global empires that had emerged over the preceding eight decades, when they displaced to a considerable degree (though not wholly) the two older Catholic-European empires that had preceded them.

Remember how, back in 1581, a clump of little Protestant provinces in West Europe’s low-lying “Netherlands” had joined together to secede from the uber-Catholic Spanish Habsburg empire that sought to retain control over them– and how England’s Protestant queen had given them extensive support in their independence battle?

How times had changed. And in the inter-imperial war that started in 1652 as at every important juncture in the emergence of West European domination over non-European nations since the Portuguese had first worked their way down West Africa in the 15th century, the deciding factor was naval gunnery.

I have already covered numerous strands in the story of the build-up to the Anglo-Dutch War that started in 1652. Today, I will first of all pull these together with the help of the excellent page that English-WP has on this war (the first of four that England and Netherlands would fight between 1652 and 1784.) Then I will look at some related news items from 1652 from the Dutch empire, in today’s South Africa and Taiwan; and from the English empire, in Barbados, Rhode Island, and India.

War between the English and Dutch

Here are the helpful excerpts from the WP page on the Anglo-Dutch war of 1652-54:

The weakening of Spanish power at the end of the Thirty Years’ War in 1648… meant that many colonial possessions of the Portuguese and some of the Spanish empire and their mineral resources were effectively open to conquest by a stronger power. The ensuing rush for empire brought the former allies into conflict, and the Dutch, having made peace with Spain, quickly replaced the English as dominant traders with the Iberian peninsula, adding to an English resentment about Dutch trade that had steadily grown since 1590. Although the Dutch wished to renew the 1625 treaty [with England], their attempt to do so in 1639 was not responded to, so the treaty lapsed.

By the middle of the 17th century the Dutch had built by far the largest mercantile fleet in Europe, with more ships than all the other states combined, and their economy, based substantially on maritime commerce, gave them a dominant position in European trade, especially in the North Sea and Baltic. Furthermore, they had conquered most of Portugal’s territories and trading posts in the East Indies and much of Brazil [though that had recently eroded a lot], giving them control over the enormously profitable trade in spices. They were even gaining significant influence over England’s trade with her as yet small North American colonies.

The WP page notes that, “The trading and shipping disparity between England and the Dutch United Provinces was growing”, giving three reasons for this:

- “the English shipping and trading system was based on duties and tariffs; while the Dutch trading system was based on free trade without tariffs and duties. Thus Dutch products would be less expensive and more competitive on the world market than English products.”

- “the end of the Eighty Years’ War (1568-1648) for Dutch independence from Spain… meant a lifting of the Spanish embargoes of the Dutch coast and Dutch shipping. This translated into cheaper prices for Dutch products due to a steep and sustained drop in Dutch freight charges and Dutch marine insurance rates.”

- “the English Civil War (1642–1651), [during which, in 1643] the English parliament began to embargo Dutch ships from trading with any ports in Great Britain in Royalist hands, which was matched later in the year by a corresponding Royalist embargo.”

The page notes that though the Dutch merchant marine was much bigger than its English counterpart, the English fighting navy was stronger, having been built up through the proceeds of a tax on merchant shipping that Parliament had imposed in 1650:

Between 1649 and 1651 the English fleet included 18 ships that were each superior in firepower to Dutch Admiral [Maarten] Tromp’s new flagship Brederode, the largest Dutch ship. All the English ships intended to fight in the battle line were more heavily armed than their equivalents in other European navies… English ships could fire and hit the enemy at a greater range.

The page gives us lots of relevant political background, too:

During the English Civil War, the Dutch Stadtholder Frederick Henry had given significant financial support to Charles I of England, to whom he had close family ties. The States General [Dutch Parliament] had been generally neutral and refused to become involved with representatives of either king or parliament; it also attempted to mediate between the two sides, an attitude that offended both English Royalists and its parliament….

After the death of Frederick Henry in March 1647, his son, the Stadtholder William II of Orange, attempted to extend the power of the stadtholderate… Following the end of the Eighty Years’ War and the execution of his father-in-law, Charles I, William attempted to support the English Royalist cause to an extent that gave concern to even his own followers, and which involved him in disputes with the more committed republicans, particularly those in Holland…

However, as we know, William II died in November 1650 just before his only son and heir was born, and Holland then entered into its First Stadtholderless Period. Any expectation that the non-monarchical nature of rule in the two countries might lead to a good relationship– or even, as some in England at the time hoped, to a “Confederation of the Two Commonwealths” was quickly disabused when diplomatic talks between the two sides in The Hague broke down in July 1651. A few months later, the English Parliament passed its (heavily protectionist) Navigation Act and the stage was set for war. At the time, influential British General George Monck explained that the major motive in passing the Act was simply that, “The Dutch have too much trade, and the English are resolved to take it from them.”

In the seven months after the Navigation Act passed, English naval and shore authorities captured and impounded more than a hundred Dutch ships trading with English ports. Among these captured were 27 Dutch ships seized in Barbados in early 1652 by Admiral George Ayscue, who was Governor of Barbados at the time.

In late May, there was an unfortunate encounter in the English Channel, near Dover, between Dutch Admiral Maarten Tromp and England’s “general at sea” Robert Blake:

An ordinance of Cromwell required all foreign fleets in the North Sea or the Channel to dip their flag in salute, reviving an ancient right the English had long insisted on. Tromp himself was fully aware of the need to give this mark of courtesy, but partly through a misunderstanding and partly out of resentment among the seamen, it was not given promptly, and Blake opened fire, starting the brief Battle of Dover. Tromp lost two ships but escorted his convoy to safety.

On July 10, the English Parliament declared war. Lots of naval battles ensued. (You can read the details on the WP page.) By March 1653, this was the situation:

The Dutch had effective control of the Channel, the North Sea, and the Mediterranean, with English ships blockaded in port. As a result, Cromwell convinced Parliament to begin secret peace negotiations with the Dutch. In February 1653, Adriaan Pauw [The Dutch “Grand Pensionary”] responded favourably, sending a letter from the States of Holland indicating their sincere desire to reach a peace agreement. However, these discussions, which were only supported by a bare majority of members of the Rump [English] parliament, dragged on without much progress for almost a year.

Despite its successes, the Dutch Republic was unable to sustain a prolonged naval war as English privateers inflicted serious damage on Dutch shipping. It is estimated that the Dutch lost between 1,000 and 1,700 vessels of all sizes to privateers in this war, up to four times as many as the English lost, and more than the total Dutch losses for the other two Anglo-Dutch war. In addition, as press-ganging was forbidden, enormous sums had to be paid to attract enough sailors to man the fleet. The Dutch were unable to defend all of their colonies and it had too few colonists or troops in Dutch Brazil to prevent the more numerous Portuguese, dissatisfied by Dutch rule, from reconquest.

Though the politicians were close to ending the conflict, the naval war continued and, over the winter of 1652–53, the English fleet repaired its ships and considered its tactics…

So I think, for 1652, I’ll leave the story there.

(The banner image above is the 1653 Battle of Scheveningen, by J.A. Beerstraaten.)

Dutch empire news

1. South Africa

In April 1652, veteran VOC official Jan van Riebeeck landed at the site of the future Cape Town with 82 men and eight women, in three ships. English-WP tells us he then:

commenced to fortify it as a way station for the VOC trade route between the Netherlands and the East Indies. The primary purpose of this way station was to provide fresh provisions for the VOC fleets sailing between the Dutch Republic and Batavia [Jakarta], as deaths en route were very high…

Van Riebeeck was Commander of the Cape from 1652 to 1662; he was charged with building a fort, with improving the natural anchorage at Table Bay, planting cereals, fruit, and vegetables, and obtaining livestock from the indigenous Khoi people… The initial fort, named Fort de Goede Hoop (‘Fort of Good Hope’) was made of mud, clay, and timber, and had four corners or bastions. This fort was replaced by the Castle of Good Hope, built between 1666 and 1679 after van Riebeeck had left the Cape…

Van Riebeeck established a vineyard in the Colony to produce red wine in order to combat scurvy…

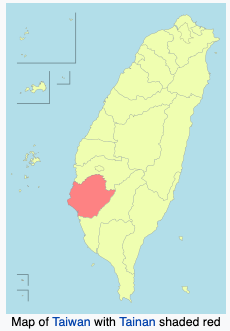

2. Taiwan

In September 1652, Guo Huaiyi (Chinese: 郭懷一; 1603–1652), a sugarcane farmer originally from Quanzhou (Fujian) led many hundreds of his supporters in attacking the Dutch stronghold of Fort Provintia with bamboo spears. The Dutch had earlier transported some 40,000 farmers from mainland China to labor in plantations on Taiwan, and those were Guo’s supporters. As for the Indigenous residents of Taiwan, at that time, after numerous previous pacification campaigns they were supporting– or not actively opposing– the Dutch.

WP explains a bit of the background to Guo’s uprising:

The burden of Dutch taxes on the Chinese inhabitants of Taiwan was a source of much resentment. The falling price of venison, a chief export of the island at the time, hit licensed hunters hard, as the cost of the licenses was based on meat prices before the depreciation. The head tax (which only applied to Chinese, not aborigines) was also deeply unpopular, and thirdly, petty corruption amongst Dutch soldiers further angered the Chinese residents.

The morning after Guo launched his uprising, this happened:

a company of 120 Dutch musketeers came to the rescue of their trapped countrymen, firing steadily into the besieging rebel forces and breaking them. On 11 September the Dutch learned that the rebels had massed just north of the principal Dutch settlement of Tayouan. Sending a large force of Dutch soldiers and aboriginal warriors, they met the rebels that day in battle and emerged victorious, mainly due to the superior weaponry of the Europeans…

Over the following days, the remnants of Guo’s army were either slaughtered by aboriginal warriors or melted back into the villages they came from, with Guo Huaiyi himself being shot, then decapitated, with his head displayed on a spike as a warning. In total some 4,000 Chinese were killed during the five-day uprising, approximately 1 in 10 Chinese living in Taiwan at that time. The Dutch responded by reinforcing Fort Provintia (building brick walls instead of the previous bamboo fence) and by monitoring Chinese settlers more closely. However, they did not address the roots of the concerns which had caused the Chinese to rebel in the first place.

A few years later it would be the Indigenes on Taiwan who rebelled against the Dutch.

English empire news

1. Rhode Island abolishes slavery

Remember Roger Williams– the English settler who expressed qualms about the fact that the settlers in North America had simply stolen the land from the Native peoples and had therefore set out to found his new colony, Rhode Island, on the basis of something like a long-term lease from the Naragansetts of the region? Under his influence, in May 1652, Rhode Island became the first European colony in North America (or perhaps anywhere in the non-European world?) to institute a ban on permanent enslavement. The PDF of the text is here.

This legislation specified a fine of “forty pounds” for non-compliance. But the slavery ban was not rigorously upheld at all; and indeed, over the decades that followed Newport RI became the North American hub of all trans-Atlantic slave-trading undertaken by the English (later British.)

2. Religious news from Barbados

In 1651, the English admiral George Ayscue (mentioned above) had been sent to Barbados by the Parliamentary authorities in London to enforce pro-Commonwealth conformity on the population of (nearly all slave-owning) English settlers there. In January 1652, he ordered that the Church of England be disestablished on the island, and passed legislation offering freedom of conscience to the settlers. In her study Christian Slavery: Conversion and Race in the Protestant Atlantic World, Katharine Gerbner notes the following (pp.39-40):

While the Commonwealth government hoped to exert more control over the colonies, it faced a massive shortage of ministers… As a result, there was no way to meet the colonial demand for ministers. It was in this environment that Quakers and other religious sectarians landed on Barbados and successfully “convinced” a number of resident. The island became a “nursery of truth” for the young Society of Friends.

What would this mean for the very widely held practice of slave-working on the island? Wait and see. (Quite likely, not what you think… )

3. Cromwell and the East India Company

Now seems as good a time as any to return to the account that English historian William Wilson Hunter’s gave in his sympathetic 1907 study of the EIC, of the relationship between Cromwell and the Company. He wrote (pp.258-60):

Cromwell viewed the India trade from a national standpoint, and regarded the Company as one of several alternative methods for conducting it. When a protracted inquiry convinced him that it was the method best suited to the times, he strongly supported it. But throughout he had the interest not of the Company, but of the nation, in mind. As he set himself, while still a cavalry colonel, to form an army of victory at home, so he resolved, as head of the Commonwealth, to create a marine which should give England predominance abroad. The Navigation Act of 1651 served as his New Model for winning the supremacy of the seas. The East India Company, its charters, and its rivals, were merely instruments for carrying out this great design.

Yet if Cromwell long stood aloof from the Company in its domestic distresses, he lost no time in dealing with its foreign enemies. In 1650 it petitioned “the Supreme Authority of this Nation, the High Court of the Parliament of England,” for help against Holland. After a list of Dutch injuries, involving an alleged loss of two millions sterling during the past twenty years, it declared that it had repeatedly laid its wrongs before the king and Council, and had prayed in vain “that satisfaction should be demanded from the States-General.” Parliament received the petition with favour, and on the same day voted that it be referred for consideration by the Council of State. But Cromwell had Scotland on his hands, and he intended, if a Dutch war must come, to wage it on wider issues. So next year, 1651, the Company twice brought its Dutch grievances before the Council of State, and again in January, 1652. Cromwell was now ready, and the wrongs of the East India Company furnished one of the causes of the war with Holland declared in the following summer. Next year the Company supplied saltpetre for [the guns of] the navy, and offered to equip a fleet of its own, which, with the aid of a few ships to be lent by the government, would turn the Dutch flank by carrying the war into the Indian seas. The proposal was not accepted, but compensation to the East India Company figured largely among the final spoils of victory.