The biggest developments of 1649 CE in the continuing development of Western hegemony of the world all centered on Oliver Cromwell. In last year’s bulletin we took his story up to the beheading of King Charles I in January 1649 and Cromwell’s announcement of an anti-monarchical Commonwealth. Throughout the rest of the year he consolidated his rule at home, including by clamping down on the more “extremist” religio-political groups like the Ranters, Levellers, and Diggers. He also clamped down extremely harshly on the remnants of the Confederacy in Ireland, who had proclaimed Charles’s son Charles II as their king. (As did the Scots.)

Cromwell went to Ireland himself to direct the anti-Catholic campaign there, which involved many massacres; and also, over the years ahead, the transportation/expulsion of thousands of Irish from their lands and a large-scale implantation of Protestant English settlers into their lands. Those campaigns in Ireland required control of the Irish Sea and all sea-lanes connecting with it; and as an adjunct to Cromwell’s campaigns on land he backed a serious revamping of the English navy which would have serious repercussions at the global level over the decades ahead (even after he was dead and the Commonwealth overthrown.)

There is once again a lot to cover in today’s bulletin. I’ll look first at two events of 1649 incidental to my main story, then at two more important stories, and finally end up with All Things Cromwell-related.

Small news

- In February 1649, the Safavid Shah Abbas II captured Kandahar from the Mughal Empire, which had held it since 1638. The Mughals tried to regain it but failed. I realize these wars among the big land empires of Eurasia– primarily these two, the Ottomans, the Chinese, and the Russians– were often massive, shape-shifting encounters. But the focus of my project is the development of Western hegemony, which was exerted primarily through maritime means. So the fates of these big land empires concern me mainly inasmuch as they interact (on their shores) with the Europe-based sea empires. But they do have nice art.

- In April 1649, the assembly of settlers of the “Maryland” colony in North America passed the “Maryland Toleration Act”. English-WP tells us that it “allowed freedom of worship for all Trinitarian Christians in Maryland, but sentenced to death anyone who denied the divinity of Jesus.” Maryland had been founded as a Catholic-English bulwark that could help protect the older, Anglican-English colony of Virginia from the encroachment of the (mainly Calvinist) Dutch “New Netherland” colony to the northwest. All the English colonies in North America and the Caribbean would soon feel the effects of Cromwellism at home.

News from Colonies

1. Iroquois attack French-Jesuit ‘strategic hamlets’ in Ontario

In March 1649, 1,000 warriors from the Iroquois or Haudenosaunee (“People of the Longhouse”) confederacy in northeast North America attacked two “mission villages” established by French Jesuits in present-day Simcoe County, Ontario. In South America, the Jesuits had established extensive networks of “mission villages”, there called “Reductions”, that in the context of the ongoing project of European-Catholic settler colonialism functioned like the strategic hamlets the US military would much later establish in Vietnam– as a way of preventing the local populations under their control from any contact with anti-colonial forces in the surrounding countryside.

The WP page on the people who were in the Jesuit-controlled villages in Ontario, who were members of the Wyandot or Huron people, tells us this:

The introduction of European weapons and the fur trade increased competition and the severity of inter-tribal warfare. While the Haudenosaunee could easily obtain guns in exchange for furs from Dutch traders in New York, the Wendat were required to profess Christianity to obtain a gun from French traders in Canada. Therefore, they were unprepared, on March 16, 1649, when a Haudenosaunee war party of about 1000 entered Wendake and burned the Huron mission villages of St. Ignace and St. Louis in present-day Simcoe County, Ontario, killing about 300 people. The Iroquois also killed many of the Jesuit missionaries, who have since been honored as North American Martyrs. The surviving Jesuits burned the mission after abandoning it to prevent its capture. The extensive Iroquois attack shocked and frightened the surviving Huron…

By May 1, 1649, the Huron burned 15 of their villages to prevent their stores from being taken and fled as refugees to surrounding tribes. About 10,000 fled to Gahoendoe (now also called Christian Island). Most who fled to the island starved over the winter, as it was an unproductive settlement and could not provide for them. After spending the bitter winter of 1649–50 on the island, surviving Huron relocated near Quebec City, where they settled at Wendake…

Colonialism loves to set the Indigenous peoples against each other, inflicting suffering on all of them…

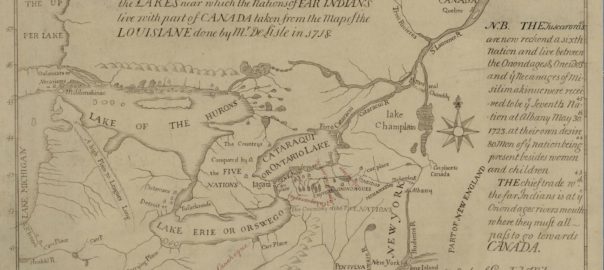

The banner image above is a 1718 map French map of these areas.

2. Indigenous Waray launch Sumuroy Revolt in Philippines

In June 1649, a leader of the Waray people in North Samar, Philippines launched an uprising against the Spanish colonial government based in Manila. WP tells us this about it:

In the town of Palapag, today in Northern Samar, Agustin Sumuroy, a Waray, and some of his followers rose in arms on June 1, 1649 over the polo y servicio or forced labor system being undertaken in Samar. This is known as the Sumuroy Revolt, named after Agustin Sumuroy.

The government in Manila directed that all natives subject to the polo are not to be sent to places distant from their hometowns to do their forced labor. However, under orders of the various town alcaldes, or mayors, the Waray were being sent to the shipyards of Cavite to do their polo y servicio, which sparked the revolt. The local parish priest of Palapag was murdered and the revolt eventually spread to Mindanao, Bicol, and the rest of the Visayas… and parts of northern Mindanao, such as Surigao. A rebel government was successfully established in the mountains of Samar.

The defeat, capture, and execution of Sumuroy in June 1650 delivered a big setback to the revolt. His trusted co-conspirator David Dula sustained the quest for freedom with greater vigor but in a fierce battle several years later, he was wounded, captured, and later executed in Palapag, Northern Samar by the Spaniards together with his seven key lieutenants.

That WP page also provides outlines of 28 other anti-colonial uprisings undertaken by Indigenous people in the Philippines against the Spanish from 1565 through 1872. Those are the ones that are known about. I shall not report them all here, but it is a truly tragic record.

3. Portuguese oust Dutch from São Tomé

To be honest, I didn’t even know that the Dutch had taken São Tomé, the island in the crook of West Africa where Portugal had been running slave-worked sugarcane plantations since 1522. But I guess the Dutch came and captured it in 1641. WP tells us this about what had been happening in São Tomé and its smaller sister-island Príncipe in the late 1630s:

[S]uperior sugar colonies in the western hemisphere began to hurt the islands. The large [population of the enslaved] also proved difficult to control with Portugal unable to invest many resources in the effort. As well, the Dutch captured and occupied São Tomé for seven years in 1641, razing over 70 sugar mills. Sugar cultivation thus declined over the next 100 years, and by the mid-17th century, the economy of São Tomé had changed. It was now primarily a transit point for ships engaged in the slave trade between the West and continental Africa.

So I guess that seven years (or so) after 1641, the Portuguese came back. Just as was happening in Brazil, the Portuguese administration and merchant community, freed since 1640 of their decades-long control by Spain, were now able to start clawing back some of the colonial prizes they had earlier lost to the Dutch.

Oliver Cromwell in England and Ireland

In late January 1649, after the court convened by the Rump Parliament had found King Charles I guilty and sentenced him to death, the leader of the New Model Army (and also parliament, I think) Thomas Fairfax, refused to sign the order for the actual beheading, but Cromwell and another officer, Colonel Hacker, did so. Charles was beheaded on January 30. This page on WP tells us what happened next:

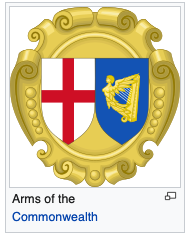

After the execution of the King, a republic was declared, known as the “Commonwealth of England”. The “Rump Parliament” exercised both executive and legislative powers, with a smaller Council of State also having some executive functions. Cromwell remained a member of the “Rump” and was appointed a member of the council. In the early months after the execution of Charles I, Cromwell tried but failed to unite the original “Royal Independents”…, which had fractured during 1648. Cromwell had been connected to this group since before the outbreak of civil war in 1642 and had been closely associated with them during the 1640s. However, only [one member of this faction] was persuaded to retain his seat in Parliament. The Royalists, meanwhile, had regrouped in Ireland, having signed a treaty with the Irish known as “Confederate Catholics”. In March, Cromwell was chosen by the Rump to command a campaign against them…

Cromwell faced opposition on many other fronts, too. Inside the New Model Army itself, the demands of the religio-political movements called Levellers, Diggers, and Ranters were becoming more intense. In April, there was a serious mutiny in the Bishopsgate area of London:

The Bishopsgate mutiny occurred… when soldiers of Colonel Edward Whalley’s regiment of the New Model Army refused to obey orders and leave London…

300 infantrymen of Colonel John Hewson’s regiment, who declared that they would not serve in Ireland until the Leveller programme had been realised, were cashiered without arrears of pay, which was the threat that had been used to quell the Corkbush Field mutiny.

When Soldiers of the regiment of Colonel Edward Whalley stationed in Bishopsgate London made similar demands they were ordered out of London. They refused to go fearing that once outside the City of London they too would be given the choice of obey or be cashiered without arrears of pay. The mutineers surrendered after a personal appeal by Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell. Fifteen soldiers were arrested and court martialed, of whom six were sentenced to death. Five were pardoned but Robert Lockier, a former Agitator within the regiment, was executed by firing squad in front of St Paul’s Cathedral on April 27, 1649.

Like the funeral of Colonel Thomas Rainsborough the previous year, Lockier’s funeral was a massive Leveller-led demonstration in London, with thousands of mourners wearing the Levellers’ ribbons of sea-green and bunches of rosemary for remembrance in their hats.

Back to Cromwell’s page on WP:

… The next month, the Banbury mutiny occurred with similar results. Cromwell led the charge in quelling these rebellions. After quelling Leveller mutinies within the English army at Andover and Burford in May, Cromwell departed for Ireland from Bristol at the end of July.

Along the way there, Parliament adopted the Act Declaring and Constituting the People of England to be a Commonwealth and Free-State, the full text of which reads:

Be it Declared and Enacted by this present Parliament and by the Authority of the same, That the People of England, and of all the Dominions and Territories thereunto belonging, are and shall be, and are hereby Constituted, Made, Established, and Confirmed to be a Commonwealth and Free-State: And shall from henceforth be Governed as a Commonwealth and Free-State, by the Supreme Authority of this Nation, The Representatives of the People in Parliament, and by such as they shall appoint and constitute as Officers and Ministers under them for the good of the People, and that without any King or House of Lords.

So then, in August, he took 30,000 NMA troops to (re-)conquer Ireland. This page on his campaigns there tells us he had four reasons for doing so:

- The first and most pressing reason was an alliance signed in 1649 between the Irish Confederate Catholics, [who proclaimed Charles II King of Ireland in January 1649, and the English Royalists… Their aim was to invade England and restore the monarchy there. This was a threat which the new English Commonwealth could not afford to ignore.

- Parliament also had a longstanding commitment to re-conquer Ireland dating back to the Irish Rebellion of 1641. Even if the Irish Confederates had not allied themselves with the Royalists, it is likely that the English Parliament would have eventually tried to invade the country to crush Catholic power there… They viewed Ireland as part of the territory governed by right by the Kingdom of England and only temporarily out of its control since the Rebellion of 1641. Many Parliamentarians wished to punish the Irish for atrocities against the mainly Scottish Protestant settlers during the 1641 Uprising. Furthermore, some Irish towns (notably Wexford and Waterford) had acted as bases from which privateers had attacked English shipping throughout the 1640s.

- The English Parliament had a financial imperative to invade Ireland to confiscate land there in order to repay its creditors. The Parliament had raised loans of £10 million under the Adventurers Act to subdue Ireland since 1642, on the basis that its creditors would be repaid with land confiscated from Irish Catholic rebels. To repay these loans, it would be necessary to conquer Ireland and confiscate such land.

- Finally, for some Parliamentarians, the war in Ireland was a religious war. Cromwell and much of his army were Puritans who considered all Roman Catholics to be heretics… The Irish Confederates had been supplied with arms and money by the Papacy and had welcomed the papal legate Pierfrancesco Scarampi and later the Papal Nuncio Giovanni Battista Rinuccini in 1643–49.

By early 1649, the (anti-Parliament) Irish Confederacy controlled all of Ireland except Ulster and the area immediately around Dublin. The pro-Parliament outpost in Dublin was commanded by a Col. Jones. This happened:

A combined Royalist and Confederate force under the Marquess of Ormonde gathered at Rathmines, south of Dublin, to take the city and deprive the Parliamentarians of a port in which they could land. Jones, however, launched a surprise attack on the Royalists while they were deploying on 2 August, putting them to flight. Jones claimed to have killed around 4,000 Royalist or Confederate soldiers and taken 2,517 prisoners.

Oliver Cromwell called the battle “an astonishing mercy” … as it meant that he had a secure port at which he could land his army in Ireland, and that he retained the capital city. With Admiral Robert Blake blockading the remaining Royalist fleet under Prince Rupert of the Rhine in Kinsale, Cromwell landed on 15 August with thirty-five ships filled with troops and equipment. Henry Ireton landed two days later with a further seventy-seven ships.

Ormonde’s troops retreated from around Dublin in disarray. They were badly demoralised by their unexpected defeat at Rathmines and were incapable of fighting another pitched battle in the short term. As a result, Ormonde hoped to hold the walled towns on Ireland’s east coast to hold up the Cromwellian advance until the winter, when he hoped that “Colonel Hunger and Major Sickness” (i.e. hunger and disease) would deplete their ranks.

From Rathmines, the army went to Drogheda, about 30 miles north of Dublin.

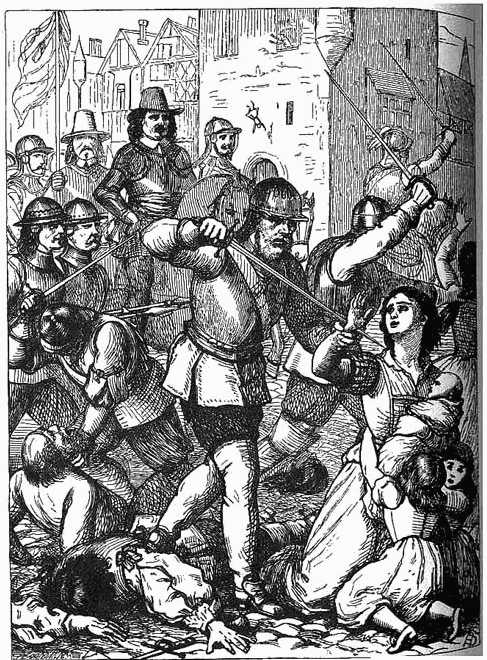

Drogheda was garrisoned by a regiment of 3,000 English Royalist and Irish Confederate soldiers, commanded by Arthur Aston. After a week-long siege, Cromwell’s forces breached the walls protecting the town. Aston refused Cromwell’s request that he surrender. In the ensuing battle for the town, Cromwell ordered that no quarter be given, and the majority of the garrison and Catholic priests were killed. Many civilians also died in the sack. Aston was beaten to death by the Roundheads with his own wooden leg.

The massacre of the garrison in Drogheda, including some after they had surrendered and some who had sheltered in a church, was received with horror in Ireland and is used today as an example of Cromwell’s extreme cruelty…

Having taken Drogheda, Cromwell took most of his army south to secure the south western ports. He sent a detachment of 5,000 men north under Robert Venables to take eastern Ulster from the remnants of a Scottish Covenanter army that had landed there in 1642…

The New Model Army then marched south to secure the ports of Wexford, Waterford and Duncannon. Wexford was the scene of another infamous atrocity: the Sack of Wexford, when Parliamentarian troops broke into the town while negotiations for its surrender were ongoing, and sacked it, killing about 2,000 soldiers and 1,500 townspeople and burning much of the town…

Arguably, the sack of Wexford was somewhat counter-productive for the Parliamentarians. The destruction of the town meant that the Parliamentarians could not use its port as a base for supplying their forces in Ireland. Secondly, the effects of the severe measures adopted at Drogheda and at Wexford were mixed. To some degree they may have been intended to discourage further resistance. The Gaelic Irish majority saw such towns as culturally English; seeing the Anglo-Irish being punished so harshly, the rural Gaelic Irish might expect even worse unless they complied with the invaders.

The Royalist commander Ormonde thought that the terror of Cromwell’s army had a paralysing effect on his forces. Towns like New Ross and Carlow subsequently surrendered on terms when besieged by Cromwell’s forces. On the other hand, the massacres of the defenders of Drogheda and Wexford prolonged resistance elsewhere, as they convinced many Irish Catholics that they would be killed even if they surrendered.

In the above accounts, I note three things:

- Of course, they were violently aggressive, colonialist, bloody, and left long and painful vestiges.

- It was appalling that one of the motivations was so that Parliament could steal the land from its owners in order to pay back its creditors.

- The key role that naval commander Robert Blake made in 1649 in keeping the lines of communication and resupply open between England and Ireland.

About Cromwell’s admiral, Robert Blake

Robert Blake was born in 1598 to a well-off family in Somerset and started off as a merchant, perhaps in Netherlands. In 1640 he was elected to Parliament, though he lost his seat soon thereafter. However he was a big supporter of the Parliamentary cause and joined the New Model Army as a Captain,distinguishing himself in fighting in many of its battles. In 1649, Cromwell appointed him “general at sea”. The title “admiral” was not used in the Commonwealth’s navy. Later, somewhat paradoxically, he became known as “the father of the Royal Navy.” This page on English-WP tells us:

As well as being largely responsible for building the largest navy the country had then ever known, from a few tens of ships to well over a hundred, he was first to keep a fleet at sea over the winter. Blake also produced the navy’s first ever set of rules and regulations, The Laws of War and Ordinances of the Sea, the first version of which, containing 20 provisions, was passed by the House of Commons on 5 March 1649, with a printed version published in 1652 as The Laws of War and Ordinances of the Sea (Ordained and Established by the Parliament of the Commonwealth of England), listing 39 offences and their punishments – mostly death. The Instructions of the Admirals and generals of the Fleet for Councils of War, issued in 1653 by Blake, George Monck, John Disbrowe and William Penn yes, that William Penn], also instituted the first naval courts-martial in the English navy.

Blake developed new techniques to conduct blockades and landings; his Sailing instructions and Fighting Instructions, which were major overhauls of naval tactics written while recovering from injury in 1653, were the foundation of English naval tactics in the Age of Sail. Blake’s Fighting Instructions, issued by the generals at sea on 29 March 1653, are the first known instructions to be written in any language to adopt the use of the single line ahead battle formation. Blake was also the first to repeatedly successfully attack despite fire from shore forts.

Back in 1649, Blake’s infant navy was able to protect Cromwell’s crossing to Ireland from the Royalist Navy brought there by Charles II’s cousin Prince Rupert. Over the five years that followed, Blake would lead the ever-growing English navy to significant victories in the First Anglo-Dutch War, an action against the Dey of Tunis, and a naval war against Spain. In a letter sent to a colleague in 1797, England’s much more famous naval leader Admiral Nelson wrote, “I do not reckon myself equal to Blake.” But all that would lie ahead…