There were a number of significant-ish developments in world history in 1635 CE, of which I’ll spend some time looking at four:

- The Dutch campaign to “pacify” the area around their fort on Taiwan by genociding the neighbors

- The expulsion by the Massachusetts Bay Colony of Roger Williams, a settler who’d argued the colonists should have paid for the land they stole

- The project launched by an intimate of England’s Charles I to implant colonial settlements in additional parts of occupied Ireland

- French PM Cardinal Richelieu’s attempt to revitalize French colony-building in the Caribbean.

Those stories all deal with the world’s rapidly expanding network of West-Europe-based maritime empires and I’ll dive deeper into them all below. In the “world” of land-based empires, it was notable that in 1635 the Zaydi (heterdox Shi-ite) imamate of Yemen was able to expel occupying forces of the strictly-Sunni Ottoman empire. Yemeni history as you may know is extremely complex. In 1632 the Zaydi imam Al-Mu’ayyad Muhammad had been able to conquer Mecca! Bad news for the Ottomans who sent a force from Egypt to get it back. Widespread fighting ensued, but by 1635 Imam Al-Mu’ayyad Muhammad had expelled the last of the Ottomans from Yemen.

Just because of its long-continuing relevance I wanted to include this short passage I found on that same English-WP page, about an earlier Egyptian (Sunni) campaign against Yemen:

Out of 80,000 soldiers sent to Yemen from Egypt between 1539 – 1547, only 7,000 survived. The Ottoman accountant-general in Egypt remarks: “We have seen no foundry like Yemen for our soldiers. Each time we have sent an expeditionary force there, it has melted away like salt dissolved in water.“

So, on to the sea-based empires…

Dutch on Taiwan genocide their neighbors

Two years ago, the Dutch VOC fought two battles against the Ming Navy and ended up winning the right to trade with the Ming empire– from, apparently, the fortified trading base, Fort Zeelandia, they had established on the southwest tip of Taiwan.

Although initially the intention was to run the colony solely as an entrepôt (a trading port), the Dutch later decided that they needed control over the hinterland to provide some security. Additionally, a large percentage of supplies for the Dutch colonists had to be shipped from Batavia at great expense and irregular intervals, and the government of the fledgling colony was keen to source foodstuffs and other supplies locally…

(I note that this is pretty similar to what happened to a lot of the Western empires that had started out engaged in “just” raiding and trading, but ended up deciding they needed to control actual land around their entrepôts, as well. That is certainly true of the English colonial positions in much of the West Indies and the North American mainland: a high proportion of them– including Roanoake Island in today’s North Carolina– had started out as “pirates’ nests” in which their ships could lurk while waiting for passing Spanish treasure fleets to capture… but then, the pirates decided they needed to sustainably resupply themselves, which meant controlling the land around their initial pirates’ nests and subduing the inhabitants thereof.)

Anyway, Taiwan.

Fort Zeelandia had never had good relations with most of the native villages around it, of which Mattau and Soulang were seen as particularly hostile. But the garrison at Zeelandia was too small to consider sending out a “pacification” expedition until 1635, when the VOC’s regional HQ at Batavia sent a force of 475 soldiers to reinforce the 210 soldiers already in the fort. At one point as they planned their campaign, this happened: “the Dutch were further encouraged by the news that Mattau and Soulang, their principal enemies, were being ravaged by smallpox, whereas Sinkan, now back under Dutch control, was spared the disease – this being viewed as a divine sign that the Dutch were righteous.”

Note the talk about “righteousness” there. It’s worth remarking that though the very Catholic Portuguese and Spanish empires had integrated priests and members of the Catholic religious orders into the operations of their colonies since the very beginning, and many of the English colonies in North America had clearly theocratic origins and operations, this was the first time in which I’d seen any reference to the diehard mercantilists of the VOC having any truck with missionaries at all. Indeed, the Dutch missionary mentioned most prominently on this page, Robert Junius, was not there just to succor the colonists and “convert” the natives– he was also one of the leaders of the military campaign the VOC’s soldiers undertook against the recalcitrant villages in 1635.

Then this:

On 22 November 1635, the newly arrived forces set out for Bakloan, headed by Governor Putmans. Junius joined him with a group of native warriors from Sinkan, who had been persuaded to take part by the clergyman in order to further good relations between themselves and the VOC. The plan was initially to rest there for the night, before attacking Mattau the next morning, but the Dutch forces received word that the Mattau villagers had learned of their approach and planned to flee. They therefore decided to press on and attack that evening, succeeding in surprising the Mattau warriors and subduing the village without a fight. The Dutch summarily executed 26 men of the village, before setting fire to the houses and returning to Bakloan…

After the victory over Mattau the governor decided to make use of the soldiers to cow other recalcitrant villages, starting with Taccariang, who had previously killed both VOC employees and Sinkan villagers. The villagers first fought with the Sinkanders who were acting as a vanguard, but on receiving a volley from the Dutch musketeers the Taccariang warriors turned and fled. The VOC forces entered the village unopposed, and burnt it to the ground. From Taccariang they moved on to Soulang, where they arrested warriors who had participated in the 1629 massacre of sixty Dutch soldiers and torched their houses. The last stop on the campaign trail was Tevorang, which had previously sheltered wanted men from other villages. This time the governor decided to use diplomacy, offering gifts and assurances of friendship, with the consequences of resistance left implicit. The Tevorangans took the hint, and offered no opposition to Dutch rule.

Having imposed their will through massive use of superior firepower, the Dutch then presided over what their historians called a “Pax Hollandica” in the area around Fort Zeelandia.

The WP page gives this scanty account of a second uprising by the indigenes 30 years later:

Multiple Aboriginal villages rebelled against the Dutch in the 1650s due to oppression like when the Dutch ordered aboriginal women for sex [and that] deer pelts, and rice be given to them from aborigines in the Taipei basin in Wu-lao-wan village which sparked a rebellion in December 1652 at the same time as the Chinese rebellion. Two Dutch translators were beheaded by the Wu-lao-wan aborigines and in a subsequent fight 30 aboriginals and another two Dutch people died, after an embargo of salt and iron on Wu-lao-wan the aboriginals were forced to sue for peace in February 1653.

Massachusetts Bay Colony expels Roger Williams

The Massachusetts Bay Colony, you will remember, was established largely congregations of people from England who were varying degrees of “extreme” Protestants– that is, not members of the Crown-established Church of England. And guess what, they had lots of religious differences among themselves, too. One settler there was Roger Williams, a Puritan minister, theologian, and author who was a follower of the “Separatist” branch of the Puritans– that is, they believed their congregations should separate from the Church of England completely.

This WP page on Williams tells us he arrived near Boston in February 1631. The “Church of Boston” offered him a job but he declined, claiming it was still “unseparated.” And this: “As a Separatist, Williams considered the Church of England irredeemably corrupt and believed that one must completely separate from it to establish a new church for the true and pure worship of God.” Another church, the one at Salem, then offered him a position– but the Boston church authorities persuaded them to rescind the offer. He then went and assisted the minister in the church at Plymouth Colony, but soon he decided that church too was insufficiently “separated” from the C of E.

And this:

Furthermore, his contact with the Narragansett Indians had caused him to question the validity of colonial charters that did not include legitimate purchase of Indian land. [Massachusetts Gov. William] Bradford later wrote that Williams fell “into some strange opinions which caused some controversy between the church and him.”

In December 1632, Williams wrote a lengthy tract that openly condemned the King’s charters and questioned the right of Plymouth to the land without first buying it from the Native Americans… Williams moved back to Salem by the fall of 1633 and was welcomed by Rev. Samuel Skelton as an unofficial assistant.

The Massachusetts Bay authorities were not pleased at Williams’ return. In December 1633, they summoned him to appear before the General Court in Boston to defend his tract attacking the King and the charter. The issue was smoothed out, and the tract disappeared forever, probably burned. In August 1634, Williams became acting pastor of the Salem church, the Rev. Skelton having died. In March 1635, he was again ordered to appear before the General Court, and he was summoned yet again for the Court’s July term to answer for “erroneous” and “dangerous opinions.” The Court finally ordered that he be removed from his church position…

Finally, in October 1635, the General Court tried Williams and convicted him of sedition and heresy. They declared that he was spreading “diverse, new, and dangerous opinions” and ordered that he be banished. The execution of the order was delayed because Williams was ill and winter was approaching, so he was allowed to stay temporarily, provided that he ceased publicly teaching his opinions. He failed to do so, and the sheriff came in January 1636, only to discover that he had slipped away three days earlier during a blizzard. He traveled 55 miles through the deep snow, from Salem to Raynham, Massachusetts where the local Wampanoags offered him shelter at their winter camp. Sachem Massasoit hosted Williams there for the three months until spring.

He later founded a new colony, the Providence Plantations” that one of the Naragansett sachems gave him the right to use (but not ownership of), and in 1647 it was chartered as the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.

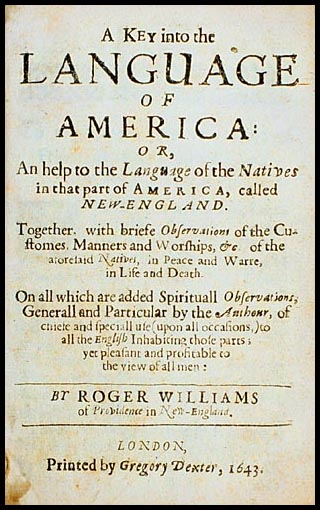

Along the way, he traveled to London in 1643 to secure that charter–arriving there in the middle of the civil war. While he was there he published a seminal work building on the tome he had spent with the Naragansetts: A Key into the Language of America. It seems to have been a fascinating volume. I found a very informative 1970 article about it by Jack L. Davis, which is on JSTOR, here. (Even better news: because of the pandemic JSTOR is letting independent scholars get access to their riches without having to have an institutional affiliation.) I hope I can share some of Davis’s information soon.

The banner image at the top here is a 19th-century image of Williams meeting the Naragansetts.

Sadly, Newport, Rhode Island pretty speedily became a key North American hub of the transatlantic trade in enslaved persons. Sigh.

Buddy of England’s King Charles expands English colonial project in Ireland

Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, had been a made a Privy Counsellor to Charles I in 1629 and in 1632 he was appointed Lord Deputy of Ireland. Soon enough while in that position he ignored Charles’ promise that no English colonists would be awarded land to the detriment of Catholic landholders, in the western province of Connaught.

English-WP tells us what Wentworth did in 1635:

he raked up an obsolete title—the grant in the 14th century of Connaught to Lionel of Antwerp, whose heir Charles was—and insisted upon the grand juries finding verdicts for the King. One county only, County Galway, resisted, and the confiscation of Galway was effected by the Court of Exchequer, while Wentworth fined the sheriff £1,000 for summoning such a jury, and cited the jurymen to the Castle Chamber to answer for their offence. In Ulster the arbitrary confiscation of the property of the city companies aroused dangerous animosity against the government…

Wentworth made many enemies in Ireland…

Some of these enemies were fellow members of the English plantocracy. And then, there were the native Irish…

Toward the native Irish, Wentworth had no notion of developing their qualities by a process of natural growth; his only hope for them lay in converting them into Englishmen as soon as possible. They must be made English in their habits, in their laws and in their religion. “I see plainly … that, so long as this kingdom continues popish, they are not a people for the Crown of England to be confident of”, he wrote.

Spoiler alert: he will not fare well in the fast-approaching English civil war.

France’s Richelieu tries to pump up colonization in Caribbean

You will recall that when the English established a colony on the island of St. Kitts, they had to share it with some French colonists (and jointly the two groups of colonists planned and executed a fearsome genocide against the indigenes.)

In 1635, Cardinal Richelieu, who was effectively the prime minister to King Louis XIII decided to transform the Compagnie de Saint-Christophe (in which the Cardinal was a shareholder) into something a little more dynamic. This venture had a broader horizon: it was called the Compagnie des Îles de l’Amérique (Company of the American Islands.)

WP tells us what happened next:

The company was charged with developing the islands of the Antilles, including converting their inhabitants to Catholicism… On 15 September 1635, Pierre Belain d’Esnambuc, French governor of the island of St. Kitts, landed in the harbour of St. Pierre [in Martinique] with 150 French settlers after being driven off St. Kitts by the English. D’Esnambuc claimed Martinique for the French King Louis XIII and the [Company of the American Islands], and established the first European settlement at Fort Saint-Pierre (now St. Pierre) under governor Jean Dupont.

It seems that d’Esnambuc had sole control of the Company, though presumably Richelieu and the king had been investors? Anyway, d’Esnambuc died prematurely in 1636, leaving the company and Martinique in the hands of his nephew, Jacques Dyel du Parquet… Du Parquet proceeded to colonize Martinique, established the first settlement in Saint Lucia in 1643, and headed an expedition that established a French settlement in Grenada in 1649.

WP tells us that, “In 1642 the company received a twenty-year extension of its charter. The King would name the Governor General of the company, and the company the Governors of the various islands.” But Richelieu died in 1642 and his successor as PM, Cardinal Mazarin, “had little interest in colonial affairs.”

In 1651, the Company “dissolved itself, selling its exploitation rights to various parties. The du Paquet family bought Martinique, Grenada, and Saint Lucia for 60,000 livres. The sieur d’Houël bought Guadeloupe, Marie-Galante, La Desirade, and the Saintes.” An interesting new model of European colonization.