The major geopolitical development in 1621 CE was the end of the Twelve Years Truce that Spain and the United Provinces of the Netherlands concluded at Antwerp in April 1609. The Dutch were ready to take advantage of the new freedom of action this afforded them on the world scene and launched a Dutch West India Company (GWC) to do so.

In Spain, King Philip III died. Spanish America saw the founding of a Mint in Bogotá and the planting of numerous other settler-colonial projects. The Spanish East Indies (Philippines) saw the establishment of a large new church in Manila.

Things continued to happen in the two English colonies in North America, Jamestown and Plymouth, but I wrote about those in 1619 and 1620 respectively. And of course in continental Europe the Thirty Years War continued to ravage large areas. But of the four big colonial powers only Spain was really involved in that (because of its continuing Habsburg affiliations.)

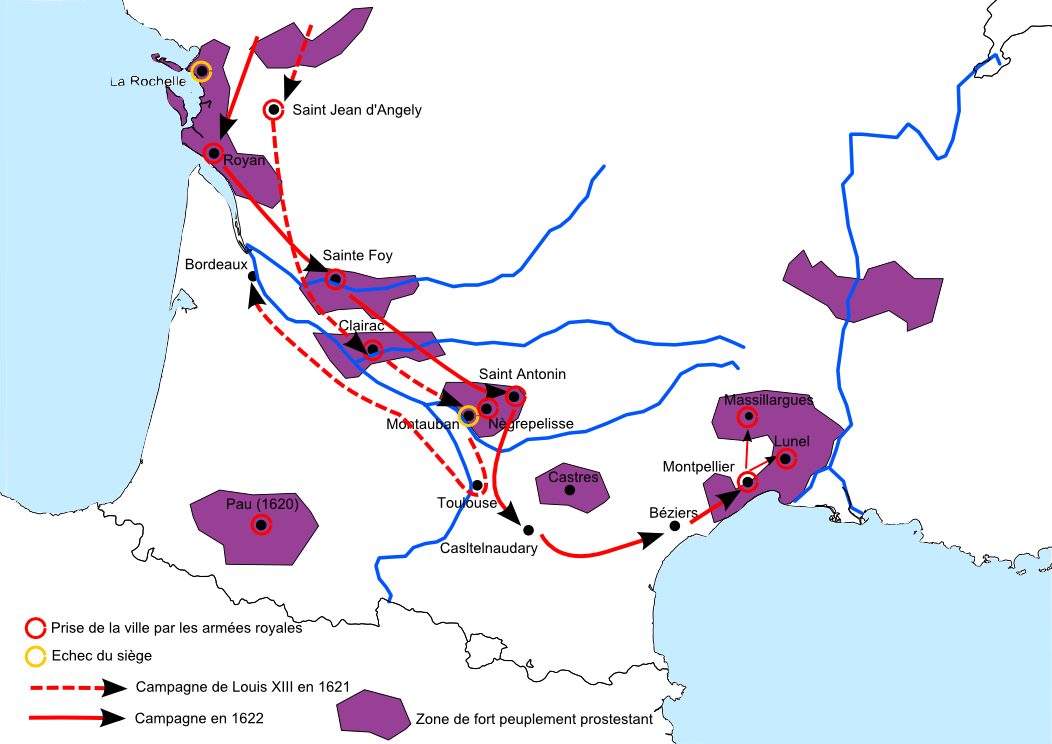

In 1621, the area of the southwest of today’s France saw fairly serious fighting between (Catholic) royal forces and the Huguenot Protestants who controlled several large towns and areas. But since France is not yet a colonial power I shan’t dwell on its internal politics.

So today’s bulletin will be all Netherlands and Spain. First, the end of the Twelve Year Truce and the founding of the GWC. Then, the Dutch VOC’s cruel 1621 campaign in Banda. Finally, a quick assessment of Philip III’s reign.

Spanish-Dutch truce ends

Back in 1609, Spain’s King Philip III and the very Protestant United Provinces of the Netherlands concluded a 12-year truce that affected both the lengthy, very destructive conflict within the European Netherlands between the Habsburg-controlled south Netherlands and the Protestant north Netherlands (the UP’s) and the various imperial projects that both those parties were pursuing on a world scale. Just to recap on the terms of that truce:

All hostilities would cease for twelve years. The two parties would exercise their sovereignty in the territories that they controlled on the date on the agreement. Their armies would no longer levy contributions in enemy territory, all hostages would be set free. Privateering would be stopped, with both parties repressing acts of piracy against the other. Trade would resume between the former belligerents. Dutch tradesmen or mariners would be given the same protection in Spain and the Archducal Netherlands as enjoyed by Englishmen under the Treaty of London…

The agreement was silent on the trade with the Indies. It did not endorse the Spanish claim to exclusive rights of navigation, nor did it back the Dutch thesis that it could trade or settle wherever there was no previous occupation by either the Spanish or the Portuguese.

Since 1580, Spain and Portugal had been united under a single monarch, though in practice the division of the world between the two Catholic powers that the Pope had negotiated back in the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas still held sway. That is, after 1580 Portuguese traders and investors continued to pursue their various commercial projects around Africa, right around and across the Indian Ocean, and in Brazil; while Spain continued its projects in the Americas and across the Pacific Ocean to the Philippines.

Though the 1609 truce had been silent on all such matters of trade with (or, more accurately, colonial exploitation of) non-European partners, in practice after 1609 the Dutch did not make any sustained push at all to challenge Spain’s or Portugal’s colonial interests in the Americas . But with their aggressive and hyper-competent VOC trading company they did make a big push to elbow aside (or blast through) the extensive Portuguese trading/exploitation networks in, especially, the Spice Islands of the East Indies, as we have seen.

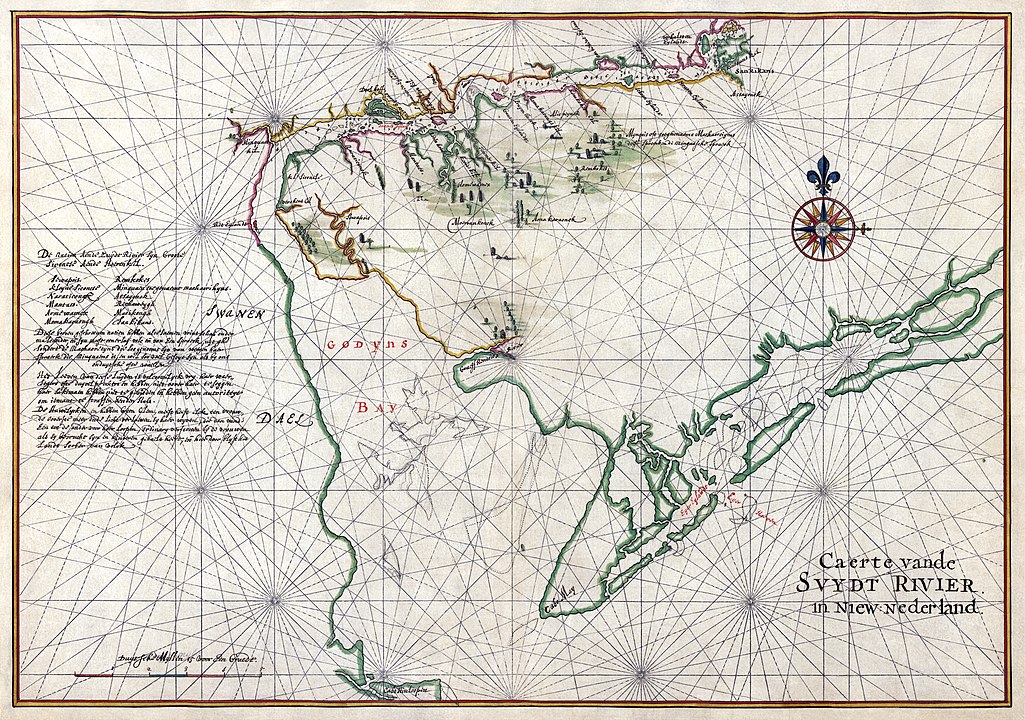

The Dutch merchants, investors, and militarists who had made such great profits already from the VOC were ready in 1621 to found a counterpart of the “West Indies.” And thus was born in June 1621 the Geoctrooieerde Westindische Compagnie (literally, the Patented West India Company), or GWC.

English-WP tells us:

The Dutch West India Company was organized similarly to the Dutch East India Company (VOC). Like the VOC, the GWC company had five offices, called chambers (kamers), in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Hoorn, Middelburg and Groningen, of which the chambers in Amsterdam and Middelburg contributed most to the company. The board consisted of 19 members, known as the Heeren XIX (the Nineteen Gentlemen)…

Investors did not rush to put their money in the company in 1621, but the States-General [parliament] urged municipalities and other institutions to invest… The VOC directors invested money in the GWC, without consulting their shareholders, causing dissent among a number of shareholders. In order to attract foreign shareholders, the GWC offered equal standing to foreign investors with Dutch, resulting in shareholders from France, Switzerland, and Venice. A translation of the original 1621 charter appeared in English… By 1623, the capital for the GWC at 2.8 million florins was not as great the VOC’s original capitalization of 6.5 million, but it was still a substantial sum. The GWC had 15 ships to carry trade and plied the west African coast and Brazil.

Unlike the VOC, the GWC had no right to deploy military troops. When the Twelve Years’ Truce in 1621 was over, the Republic had a free hand to re-wage war with Spain. A Groot Desseyn (“grand design”) was devised to seize the Portuguese colonies in Africa and the Americas, so as to dominate the sugar and slave trade. When this plan failed, privateering became one of the major goals within the GWC. The arming of merchant ships with guns and soldiers to defend themselves against Spanish ships was of great importance. On almost all ships in 1623, 40 to 50 soldiers were stationed, possibly to assist in the hijacking of enemy ships.

Long story short, in its early years the GWC was pretty unsuccessful, though its did pursue projects to establish a colony at the mouth of the Delaware River, and another on the coast of Brazil… Let’s keep watching.

A few last notes about the truce of 1609 and its lapsing:

- The person on the Dutch side who had been most insistent about agreeing only to a truce that had a restricted term had been Johan Van Oldenbarnevelt, the legal-genius grandfather of both the Dutch independence project and the VOC. But as we saw, a couple years ago, JVO had been executed in The Hague because religious differences between him and Stadtholder (president-ish) Mauritz of Nassau had threatened to escalate to a civil war. Still, from the Dutch mercantilists’ point of view, JVO had done well in his truce negotiations.

- The main thing the Dutch had gotten out of the truce was a growing recognition from other political leaders in Europe of their political independence from the Habsburg Empire. They kept that even after the truce lapsed.

- The main thing the Spanish side had gotten out of the truce was some relief from the costs of continuing the big land and sea battles they’d been waging against the UPs until then. By the time the truce lapsed, Madrid was deeply engaged in the Thirty Years War in much of the rest of continental Europe. Would it also seek to restart the war against the UPs? (Scroll on down to find out.)

Dutch VOC violently seizes Banda Islands

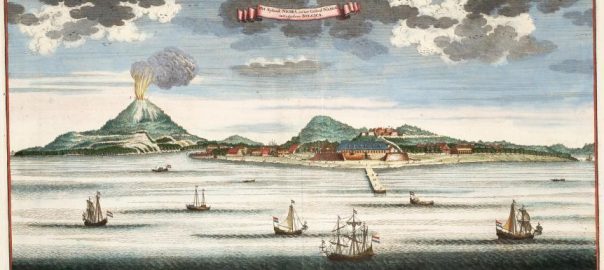

The 13 Banda Islands are tiny specks of land in the Banda Sea, midway between Timor and New Guinea. Their big attraction to European colonial plunderers was that they formed the hub of cultivation of the extremely profitable spice, nutmeg. In 1621, the VOC’s arrogant governor-general (who had had a previous, pretty humiliating run-in with the fierecely nationalistic Bandanese) arrived in Banda and set about very violently bending them to his will.

Of the Europeans who came to the Bandas, the Portuguese had been the first to arrive: an armed Portuguese trading delegation arrived there in 1511. That expedition, “remained in Banda for about one month, purchasing and filling their ships with Banda’s nutmeg and mace, and with cloves in which Banda had a thriving entrepôt trade.” The Portuguese did not return till 1529, when another Portuguese trader

realised that a fort on the main island Neira would give him full control of the group. The Bandanese were, however, hostile to such a plan, and their warlike antics were both costly and tiresome to Garcia whose men were attacked when they attempted to build a fort. From then on, the Portuguese were infrequent visitors to the islands preferring to buy their nutmeg from traders in Malacca.

Unlike other eastern Indonesian islands… the Bandanese displayed no enthusiasm for Christianity or the Europeans who brought it in the sixteenth century, and no serious attempt was made to Christianise the Bandanese. Maintaining their independence, the Bandanese never allowed the Portuguese to build a fort or a permanent post in the islands

Let’s fast-forward through several other inter-imperial battles for control of the region and access to its extremely profitable resources. In 1621, this happened:

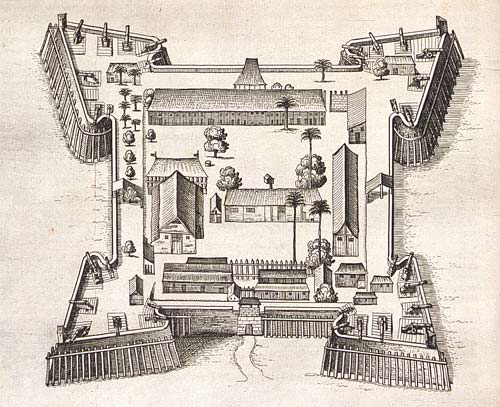

Newly appointed VOC governor-general Jan Pieterszoon Coen set about enforcing Dutch monopoly over the Banda’s spice trade. In 1621 well-armed soldiers were landed on Bandaneira Island and within a few days they had also occupied neighbouring and larger Lontar. The orang kaya [that is, the leaders of the indigenous community] were forced at gunpoint to sign an unfeasibly arduous treaty, one that was in fact impossible to keep, thus providing Coen an excuse to use superior Dutch force against the Bandanese. The Dutch quickly noted a number of alleged violations of the new treaty, in response to which Coen launched a punitive massacre. Japanese mercenaries were hired to deal with the orang kaya, forty of whom were beheaded with their heads impaled and displayed on bamboo spears…

The islanders were tortured and their villages destroyed by the Dutch…

The population of the Banda Islands prior to Dutch conquest is generally estimated to have been around 13,000–15,000 people, some of whom were Malay and Javanese traders, as well as Chinese and Arabs. The actual numbers of Bandanese who were killed, forcibly expelled or fled the islands in 1621 remain uncertain. But readings of historical sources suggest around one thousand Bandanese likely survived in the islands, and were spread throughout the nutmeg groves as forced labourers. The Dutch subsequently re-settled the islands with imported slaves, convicts and indentured labourers (to work the nutmeg plantations), as well as immigrants from elsewhere in Indonesia. Most survivors fled as refugees to the islands of their trading partners, in particular Keffing and Guli Guli in the Seram Laut chain and Kei Besar.Shipments of surviving Bandanese were also sent to Batavia (Jakarta) to work as slaves in developing the city and its fortress. Some 530 of these individuals were later returned to the islands because of their much-needed expertise in nutmeg cultivation (something sorely lacking among newly arrived Dutch settlers).

The conquest of the Bandas marked a turning point for the Dutch in the East Indies. English-WP tells us that: “Whereas up until this point the Dutch presence had been simply as traders, that was sometimes treaty-based, the Banda conquest marked the start of the first overt colonial rule in Indonesia, albeit under the auspices of the VOC.”

(The banner image above is a 1724 view of Bandaneira.)

Spain’s King Philip III dies

After 23 years on the throne, King Philip III of Spain (also Philip II of Portugal) died in March 1621. The early years of his reign were marked by his conclusion of a peace treaty with England’s ageing Queen Elizabeth and of the Twelve-Year Truce with the Netherland UP’s.Like his predecessors on the Spanish throne he placed great “foreign policy” focus on strengthening the Habsburg position in Europe (though he probably didn’t consider this to be foreign policy.) He and his predecessor, Philip II, were perennially short of cash because of the costs of Spain’s European wars. That cash-shortage probably helped push this Philip into the truce with the UPs. The peace with England was probably motivated by a combination of cash-shortage, plus the inability of Spain’s armed forces to effect a successful invasion of England, plus the continuing desire of European monarchs like Philip to keep the way open for doing clever “diplomatic” deals through strategic marriages.

That focus on Europe meant he did not pay much discernible attention to the continuing growth and development of Spain’s transoceanic empire. His main requirement from the empire was that it continue sending him silver and gold to fund his wars in Europe. I suppose that he, like the heads of all empires, got some non-trivial emotional jollies from hearing good news about “his” empire; but he seemed to leave most of the details of administering it to the many seasoned military leaders who led its various portions and the various Catholic religious orders who were an essential part of the Spanish plan plan to subdue all the natives by Christianizing them– by force if necessary.

He was succeeded by his 15-year-old, Philip IV (III). The new Philip’s main advisor at that time was Gaspar de Guzmán, the Count-Duke of Olivares. During Philip’s early years on the throne, Olivares would wake him first thing in the morning with a report then have two or three other meetings with him each day.

English-WP tells us that,

For twenty-two years Olivares directed Spain’s foreign policy. It was a period of constant war, and finally of disaster abroad and of rebellion at home. Olivares’ foreign policy was based around his assessment that Philip IV was surrounded by jealous rivals across Europe, who wished to attack his position as a champion of the Catholic Church; in particular, Olivares saw the rebellious Dutch as a key enemy.

Well, the Twelve Year Truce has just ended. That could therefore mean a bad flare-up is ahead between Spain and the UPs…