Amb. Robert E. Hunter had a compelling piece on the Lobelog site recently in which he warned that the House Democratic leaders’ choice of the Ukraine issue on which to hang their impeachment hearings for Pres. Trump means that the discussion of both Ukraine and Russia in the U.S. political system has now become seriously polarized.

Hunter understands well what is at stake. From 1993 through 1998, he was the U.S. ambassador to NATO, where one of his major tasks was to help Washington and its NATO allies build the post-Soviet order in Europe.

I think, though, that Hunter understates the degree to which a kind of mindless Russophobia (or what we might call “Maddow-brain”) has taken grip of much of the Democratic Party machine. But in the gloom that pervades his piece, he also underestimates the ability of most grassroots Democrats to think sensibly and with some nuance about these things.

After all, can’t a reasonable person believe both that the President should face trial because of his use of governmental resources for personal political gain and that the United States needs to pursue policy toward Russia in a calm, informed way based on an appreciation that escalating tensions with Moscow (over Ukraine, over Syria, or anything else) is in nobody’s interest at all?

So just how deeply has knee-jerk Russophobia sunk its roots into the Democratic Party machine and allied portions of the big corporate media?

Hunter is right to note that it goes back earlier than the launching of the current impeachment hearings. He writes that back in 2016,

many Democrats could not accept that a large part of the reason for Hillary Clinton’s loss derived from a poorly run campaign, as well as reaction against the bicoastal elites… The charge by many Clinton supporters was that Russian interference in the U.S. election was a prominent, perhaps decisive, factor in Trump’s election. It thus became a major issue in U.S. domestic politics, overshadowing other causes for Clinton’s defeat.

But it is possible to argue that an uninformed hostility to Russia goes back much further than 2016, too… Back, indeed, to many of the actions of the Bill Clinton administration (in which Hunter himself had served.) After all, soon after Clinton came into office in 1992 he reneged on the serious promise Secretary of State James Baker gave the Russians in February 1990 that if Russian Pres. Gorbachev agreed that a newly reunited Germany could join NATO– as he did– then NATO would not expand one inch further east than the borders of Germany.

The Clintonites’ “betrayal” of the Baker undertaking was very consequential. During the 1990, as NATO marched ever further eastward, that told a whole generation of Russians that their country counted for nothing to a Washington that seemed determined to encircle them with a hostile, Washington-led military alliance. Those Russian fears and resentments provided fertile ground for the emergence of a “strong” leader like Pres. Putin, who was determined to end and reverse the implosion of Russian power that had occurred under Boris Yeltsin…

The Clintonites’ expansion of NATO also led almost directly to the twin crises over Georgia and Ukraine that we’ve seen in the present decade. In both countries, the desire of some of the citizens to join not just the European Union but also NATO (which was strongly encouraged– or even incited– by Washington) provoked angry pushback from Moscow and from those of their own compatriots who wanted to retain good ties to Russia.

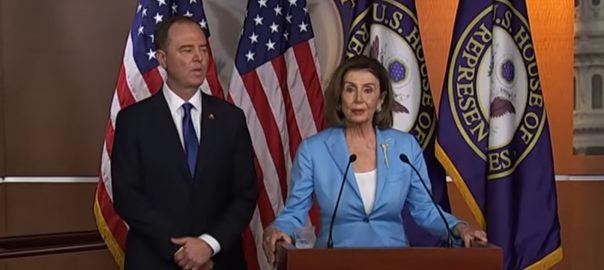

Good accounts of the past few years’ events in Ukraine can be found in two recent articles by veteran CIA Russia analysts Melvin Goodman and Ray McGovern. Both accounts provide a strong challenge to the simplistic way Intelligence Committee Chair Adam Schiff framed these events when he opened the first public impeachment hearings November 13.

Schiff’s words were,

In 2014, Russia invaded a United States ally, Ukraine, to reverse that nation’s embrace of the West, and to fulfill Vladimir Putin’s desire to rebuild a Russian empire…

Well, actually, no. Ukraine has no formal alliance with the United States. A general friendship is very different from an alliance. Also, as Goodman and McGovern both noted, the sequence of events in Ukraine in 2014 had started not with a Russian invasion but earlier, with a massive U.S. intervention in the country’s presidential election that was classified by many at the time as a coup.

Notably, neither Goodman nor McGovern were able to publish their pieces of very well informed analysis in any part of the big corporate media. For the most part, big newspapers like The New York Times and The Washington Post have simply gone along with Schiff’s misleading and Russophobic description of Ukrainian events and the role Russia has played there.

In the 27 years since 1992, much of the Democratic Party has become dangerously suffused with the kind of unthinking Russophobia that throughout earlier decades had characterized the GOP.

One current example: In Kentucky, the Democrat who will challenge Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell in next year’s election has for some months now been ridiculing him as “Moscow Mitch”. Presumably, this has proven a productive fundraising strategy, since the Dems have intensified it since they first launched the name back in July. Right now they are even selling “Moscow Mitch” wrapping paper, that their supporters can buy in time for the upcoming holidays…

Don’t get me wrong. As a woman and as someone with daughters and grand-daughters (and just as a citizen!), I can see hundreds of excellent reasons to oppose Sen. McConnell. So why do the Kentucky Dems, and whatever national party organizations are helping them out, pick on this dangerous and silly trope as a centerpiece of their attack on him?

There’s a broader problem here, too. Throughout the Cold War, there was a potent saying– and a generally respected practice– here in the United States that “Politics should stop at the water’s edge.” In other words, Americans should not allow party-political considerations to impinge on their consideration of relations with other countries. (It is this very principle that Pres. Trump today stands accused of infringing.)

But in the years since 2016, many in and friendly to the Democratic Party machine have been guilty of almost exactly the same thing! Any move that Trump has made in his foreign policy, these Dems have opposed simply because he made it. Withdraw from Syria? Seek a peace settlement with the Taliban in Afghanistan or a deal with North Korea? Most of the Democratic Party machine looks at those proposals not on their merits, but simply on the basis that Trump has made them… and instantly comes out against them.

(And the Raytheons, Boeings, Lockheed Martins, Northrup Grummans, and all the other grim reapers of the military-industrial complex? They just love the prospects of the profits that Washington’s forever wars can keep on bringing…)

Again, a caveat: There are plenty of areas of Trump foreign policy in which his policies should certainly be opposed. These include his exits from the JCPOA with Iran, from the Paris Climate Treaty, and the last remaining arms control agreements with the (former) Soviet Union.

But people of any political party who are concerned about those arrogant, Trumpian displays of American unilateralism need to be able to discuss the whole gamut of foreign policy issues in a calm, reasonable, and fact-based way– not simply to say that “If Trump pursues any foreign policy initiative then it must for that reason alone be wrong.”

Amb. Hunter seems to think this situation is impossible to change. “U.S. domestic politics has become the sole focus for thinking about Ukraine, as well as about Russia,” he writes, gloomily.

Call me an idealist if you want, but I beg to disagree. I think there are still enough thinkers and activists left at the Democratic grass roots who are not still smarting from Hillary’s 2016 defeat and who are prepared to be smarter than Schiff and Co. in how they think about foreign-policy issues. They can walk and chew gum at the same time; and they can judge foreign-policy questions on a much broader and smarter basis than by simply concluding that everything Trump does is ipso facto wrong. May they (we) grow in power!

Finally, one last important note here on Ukraine and Russia.

Much of the narrative in U.S. corporate media has fallen into the simplistic binary of assuming that everything Russia does is bad, and everything Ukraine does is good (especially if they want to fight against Russia!)

But Ukraine’s 42 million people are far from united in wanting to “embrace” the West or to confront Russia. Indeed, the country’s popular young president, Volodymyr Zelensky (a native Russian speaker), was elected just this past May on a platform that stressed both the need to combat corruption and the need to resolve Kyiv’s conflict with Russia. Then in July, just days before his controversial phone call with Trump, Zelensky’s “Servant of the People” party won 254 of the 424 seats in the Ukrainian parliament.

Now, Zelensky and Putin are both scheduled to take part in a meeting French President Emmanuel Macron is planning for December 9, in Paris. The topic will be steps they both can take to de-escalate the armed conflicts currently roiling Eastern Ukraine. Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel is expected to attend. Trump is not.

How many members of the U.S. Democratic leadership or the corporate media’s punditocracy will be rooting for the success of these meetings– or even, paying any heed to them? I shall be doing both.

3 thoughts on “U.S. Dems’ dangerous demagoguing on Russia”

Comments are closed.