Yesterday, 1612, I quoted English historian William Wilson Hunter as pinpointing the firman that Mughal Emperor Jahangir gave to English sea-captain Thomas Best in January 1613– after Best’s naval victory over a much larger Portuguese at Surat– as being England’s first “legal settlement on the Indian continent.” That sounds as good a starting point as any for what would, over the centuries that followed, become the massive and massively rapacious English/British presence in India. In his 1907 work of history, WWH explained some of the specifics of how the English, once installed in Surat, were able to disrupt the lines of communications that Portugal had long relied on in the Arabian Sea– chiefly between the key port cities of Dui and Goa– and then to dislodge them.

While the English EIC was making some small advances in dislodging the Portuguese from India’s west coast, the Dutch VOC had been making even greater strides in displacing the Portuguese from the East Indies. So now, for 1613 CE, I will take a quick look at what the well-armed, well-organized merchant-plunderers of the infant polity of Protestant Netherlands were up to there– and in the Caribbean. Then I’ll race through the other stories of the year.

The Dutch in the East Indies and Suriname

We will recall that when the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was founded in 1602, it had a starting capital that was considerably larger than that of the English EIC, founded two years earlier. It also had a longer term, in the charter it was granted by the Dutch “States-General”– 21 years, as opposed to the EIC’s terms, which had to be granted anew every four years.

English-WP notes these facts about the early years of the VOC:

- “The new company’s charter empowered it to build forts, maintain armies, and conclude treaties with Asian rulers. It provided for a venture that would continue for 21 years, with a financial accounting only at the end of each decade.”

- “For a time in the seventeenth century, it was able to monopolise the trade in nutmeg, mace, and cloves and to sell these spices across European kingdoms and [the] Mughal Empire at 14-17 times the price it paid in Indonesia; while Dutch profits soared, the local economy of the Spice Islands was destroyed.”

- “In February 1603, the company seized the Santa Catarina, a 1500-ton Portuguese merchant carrack, off the coast of Singapore. She was such a rich prize that her sale proceeds increased the capital of the VOC by more than 50%.”

- “In 1603, the first permanent Dutch trading post in Indonesia was established in Banten, West Java, and in 1611, another was established at Jayakarta (later “Batavia” and then “Jakarta”).”

In 1613, the VOC’s headquarters appointed a man called Jan Pieterszoon Coen to be accountant-general of all VOC offices in the East Indies, and president of the head offices in Bantam and Jakarta. Coen, a strict Calvinist, had earlier studied book-keeping with a Flemish company in Rome.

Later, Coen would rise to become the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies and we’ll hear more about him. But for now it is instructive to note that while the English EIC’s victory in Surat the year before had relied only on a single, slightly prolonged, demonstration of naval prowess at sea– following which the victorious Captain Best and his fleet had very speedily sailed away to his next ports of call, in Sri Lanka and Sumatra, over in the East Indies the VOC not only had two “permanent” (and presumably well-fortified) trading posts, but also a growing cadre of semi-permanent administrators to run them.

I guess that is what having adequate capitalization and not having to present your accounts to your investors every years allows you to do.

Suriname

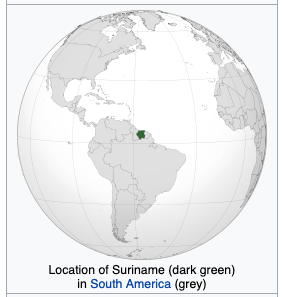

And the East Indies was not the only location in which the ever profit-seeking armed traders of the infant Dutch Republic were eager to tweak the imperial interests of their long-time Spanish/Portuguese tormentors. Over on the north coast of South America, in 1613 a couple of Dutch guys called Nicolaes Baliestel and Dirck Claeszoon van Sanen established a trading post that they called Paramaribo.

I’m not sure how long that one lasted. English-WP tells us that it and all other European settlements in the vicinity were abandoned when English settlers arrived in 1650 to found another settlement in that place, which they called Surinam. Then this: “In 1667, during the Second Anglo-Dutch War, Paramaribo was conquered by a squadron of [Dutch] ships under Abraham Crijnssen. The Treaty of Breda in 1667 confirmed Paramaribo as the leading town of the now Dutch colony of Suriname.”

Suriname would remain under Dutch control until it became an independent state in 1975. But the Dutch founding of Paramaribo in 1613 signaled not just that infant Netherlands was speedily flexing long-distance imperial/colonial muscles but also that one of the coming locations of inter-imperial contest would be the Caribbean.

Moscow greets the Romanov era

I’ve been intermittently tracking some of the political upheavals in Moscow, there the previous Rurikid dynasty of Ivan the Terrible had, after his death in 1575, disintegrated into warring factions involving False Dimitri I, False Dimitri II, and various other characters, some of them backed by Poland… In 1613, the feudal-style boyars who were the main ones jockeying for power in Moscow/Russia finally found a compromise candidate for the tsardom on whom they could agree, and I suppose they all heaved a large collective sigh of relief. I mean, how many False Dimitris can a country put up with?

This new guy was 17-year-old Michael Romanov, who had two tangled claims to links with the Rurikids– one, through his great-aunt Anastasia and one through somebody’s marriage.

That was good enough for the zemsky sobor (national assembly) that convened in Moscow in February 1613 to elect young Michael unanimously to be Tsar. But it took them a further month to find the young man, whose mother (a nun) was hiding out with him at a monastery some distance away.

English-WP tells us:

In so dilapidated a condition was the capital at this time that Michael had to wait for several weeks at the Troitsa monastery, 75 miles (121 km) off, before decent accommodation could be provided for him at Moscow. He was crowned on 22 July 1613, on his seventeenth birthday. The first task of the new tsar was to clear the land of the countries occupying it. Sweden and Poland were then dealt with respectively by the peace of Stolbovo (17 February 1617) and the Truce of Deulino (1 December 1618). The most important result of the Truce of Deulino was the return from exile of the tsar’s father, who henceforth took over the government till his death in October 1633, Michael occupying quite a subordinate position.

Michael’s reign saw the greatest territorial expansion in Russian history. During his reign, the conquest of Siberia continued, largely accomplished by the Cossacks and financed by the Stroganov merchant family.

Spanish-Sicilian adventurer defeats Ottoman fleet near Izmir

In 1610, the Habsburgs had installed as Viceroy in Sicily the Duke of Osuna, whose goals were described as being to eliminate banditry on the island and restore its naval strength. By July 1612, he had built eight galleys and several sailing vessel; and he entrusted command of the navy to a guy called Ottavio d’Aragona. Over the months that followed, d’Aragona made several successful raids against Ottoman positions along the Mediterranean’s south coast. In 1613, he headed east to the Aegean, where he was informed of an Ottoman fleet lying at anchor off Cape Corvo, not far from Izmir on the Turkish mainland.

After a three-hour battle, d’Aragona emerged victorious. Of the 10 Ottoman galleys in the bay, he captured seven. He killed an estimated 400 Ottomans, took 600 prisoners, and freed 1,200 Ottoman galley-slaves. English-WP tells us that, “Among the most prominent prisoners were [Ottoman fleet commander] Sinari Pasha, who died of sorrow shortly after, and Mahamet, Bey of Alexandria and son of Müezzinzade Ali Pasha, who had commanded the Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Lepanto.”

The Sicilian/Spanish losses in the battle were very low.

English and French colonizing projects in N. America

In 1613, in the area of North-eastern America to the north of where the Spanish were colonizing Florida, the main inter-imperial contest was between the English and French (though the Dutch would be coming soon.)

In October 1613, the tiny fortified French settlement of Port Royal that Samuel Champlain and his colleagues had founded on the northwest coast of today’s Nova Scotia was attacked and destroyed by a force led by the “Admiral of Virginia”, Samuel Argall.

WP tells us that “Argall surprised the settlers at Port-Royal and sacked every building. The battle destroyed the Habitation but it did not wipe out the colony. Biencourt and his men remained in the area of Port-Royal (present day Port Royal, Nova Scotia). A mill upstream at present day Lequille, Nova Scotia remained, along with settlers who went into hiding during the battle.”

English control did not last long. In 1631, England and France signed a treaty under which the English ceded Port-Royal back to the French. See where the various countries’ colonists had gotten to by 1664, at right.

But meantime back in Virginia, in 1613, some of the English colonists captured the young Powhatan princess Pocahontas and held her for ransom:

During her captivity, she was encouraged to convert to Christianity and was baptized under the name Rebecca. She married tobacco planter John Rolfe in April 1614 aged about 17 or 18, and she bore their son Thomas Rolfe in January 1615.

(The banner image at the top of this page is a wholly fanciful, 19th-century painting of “The Baptism of Pocohontas.”)

By the way, Rolfe was the first English settler in Virginia who was able to grow and start exporting tobacco that was “sweet” enough for English tastes. He was one of the survivors of George Somers’s earlier shipwreck on Bermuda, where his first wife and child had died.

Pocahontas’s whole page on WP is pretty interesting. It tells is this:

In 1616, the Rolfes travelled to London where Pocahontas was presented to English society as an example of the “civilized savage” in hopes of stimulating investment in the Jamestown settlement… She became something of a celebrity, was elegantly fêted, and attended a masque at Whitehall Palace. In 1617, the Rolfes set sail for Virginia, but Pocahontas died at Gravesend of unknown causes, aged 20 or 21. She was buried in St George’s Church, Gravesend, in England, but her grave’s exact location is unknown because the church was rebuilt after a fire destroyed it.

Apparently one of the reasons Rolfe and his Virginia Company colleagues were so eager to show off Pocohontas to London society was because every so often they remembered that part of their stated mission in America was to spread (the Church of England version of) Christianity. She was one of the notably small number of their converts to date…