Some interesting events, eddies, and side-eddies in world history in 1599 CE. I think we have to start in Ireland:

Elizabeth’s protege the Earl of Essex fails badly in Ireland

Robert Devereux, the 2nd Earl of Essex, born in 1565, had at one stage been quite a favorite of the queen, who was a distant cousin. He came to court in 1584, soon replaced his stepfather as Master of the Horse, was appointed to her close circle of advisors (the Privy Council), and was awarded by her with a monopoly on sweet wines which was quite lucrative. He took part in the “English Armada” of 1589 and then distinguished himself in the Capture of Cadiz in 1596. In 1597, he had led the “Island Voyage” against Spanish positions in Jamaica.

Now, in 1599, she appointed him “Lord Lieutenant of Ireland” and gave him the largest English expeditionary force ever sent there– 16,000 troops– with orders to put down the still-continuing Irish rebellion, which had spread from Ulster to all of Ireland. They arrived in April but instead of following advice from previous English commanders in Ireland to try to defeat the rebels in Ulster, Essex and his prime military commander Conyers Clifford decided to go south from there, leaving men in garrisons along the way.

The prime leaders of the rebellion were Hugh O’Neill (whom we’ve met before) and Hugh Roe O’Donnell (Irish: Aodh Ruadh Ó Domhnaill), also known as Red Hugh O’Donnell.

This page on English-WP tells us that as the ever-diminishing English force approached the town of Boyle in early August:

The Irish then carefully prepared an ambush site in the Curlew Mountains, along the English line of march. O’Donnell had trees felled and placed along the road to impede their progress. When he got word of the English passing through Boyle, O’Donnell positioned his men. Musketeers, archers, and javelin men were placed in the woods alongside the road to harass the English soldiers. The main body of Irish infantry, armed with pikes and axes, were placed out of sight behind the ridge of the mountain.

By the time Clifford and his men, who by that point numbered around 1,700, reached Curlew Pass, the ambush force of around 2,500 Irish were ready; and though the English showed some fight the Irish were able decisively to beat them:

The commander of the vanguard, Alexander Radcliffe, could no longer control his troops. They wheeled about in a panic and collided with the main column, which broke and fled. The commander led a charge with his remaining pikemen but was shot dead in that action. With the English ranks in disarray, the main body of Irish infantry, which had concealed itself on the reverse slope of the hill, closed in and fought hand-to-hand. Clifford tried to regain control over his men, but appeared overcome by his circumstances. He managed to rally himself and was killed by a gun-shot through the chest as he rushed the enemy. Despite his death, the rearguard managed to maintain some semblance of formation and continued to fight on as others fled the field…

Brian Óg O’Rourke, who had led the Irish soldiers on the ground, “ordered Clifford’s head to be cut off and delivered to O’Donnell – who had remained nearby, but without taking part in the fight.”

Some time then or soon thereafter, the Earl of Essex decided to, essentially, cut and run. He concluded a hasty truce with the rebels and returned back to London in late September.

Back to Essex’s page on WP:

The Queen had expressly forbidden his return and was surprised when he presented himself in her bedchamber one morning at Nonsuch Palace, before she was properly wigged or gowned. On that day, the Privy Council met three times, and it seemed his disobedience might go unpunished, although the Queen did confine him to his rooms with the comment that “an unruly beast must be stopped of his provender.”

On September 29, he was forced to “stand before the Council during a five-hour interrogation. The Council—his uncle William Knollys, 1st Earl of Banbury included—took a quarter of an hour to compile a report, which declared that his truce with O’Neill was indefensible and his flight from Ireland tantamount to a desertion of duty.”

During his earlier time as the queen’s favorite, Essex had aroused the considerable ire of the queen’s private secretary, Robert Cecil; and there were evidently many more at court, too, who opposed him.

In June 1600 he was tried,

before a commission of 18 men. He had to hear the charges and evidence on his knees. Essex was convicted, was deprived of public office, and was returned to virtual confinement. In August, his freedom was granted, but the source of his basic income—the sweet wines monopoly—was not renewed. His situation had become desperate, and he shifted “from sorrow and repentance to rage and rebellion.” In early 1601, he began to fortify Essex House, his town mansion on the Strand, and gathered his followers.

On February 8, 1601, he “marched out of Essex House with a party of nobles and gentlemen… and entered the city of London in an attempt to force an audience with the Queen. Cecil immediately had him proclaimed a traitor.” There were a couple of skirmishes in the street but then Essex surrendered.

There was a speedy trial, in which he was convicted on charges of, “conspiring and imagining at London, . . . to depose and slay the Queen, and to subvert the Government.”

On February 25, 1601 he was the last person to be beheaded in the Tower of London.

As for the fate of the Irish rebellion– we shall see.

Safavid Shah’s chaotic diplomatic mission to Europe

After the Safavid Shah Abbas succeeded to the throne in 1588, one of his earliest initiatives was to negotiate a peace with the Ottomans. Now, in 1599, he decided to try to build alliances with as many European powers as possible, which might be useful ion the event of any renewed hostility with the Ottomans (which, actually, he was already preparing for.)

The diplomatic mission that he sent out from his capital, Qazvin, in July 1599, was composed of one ambassador, Hossein Ali Beg, and four secretaries. And pretty surprisingly it was led by an English adventurer called Anthony Shirley, who had sailed in from Venice just two months earlier, with 25 other Englishmen. (Shirley had previously participated in many of the English overseas expeditions that we’ve described here previously, including the Essex-led raid on Spanish Jamaica. He had reached Qazvin from Venice via Constantinople and Aleppo; and Shah Abbas had made him a “mirza“, or prince.)

So, back to the diplomatic mission: The embassy left in July 1599 for Astrakhan. They reached Moscow in November 1599. But almost immediately, relations between Hossein Ali Beg and “Sir” Anthony Shirley soured– and their “embassy” suffered from other challenges too.

This, from the WP page on Hossein Ali Beg:

[In Moscow] Hossein Ali Beg and Sir Anthony quarreled over who should have precedence, but Tsar Boris Godunov chose Hossein Ali Beg’s side and even imprisoned Sir Anthony for some time after the Portuguese friar, Nicoloa de Melo made certain accusations against him. In the spring of 1600, Hossein Ali Beg and his retinue left Moscow, and after several stops at various German courts, they eventually arrived in the capital of the Holy Roman Empire, Prague in the autumn of 1600. There, where they were lavishly received, emperor Rudolph II who was already at war with the Ottomans, vowed to pursue the war against them with “great vigour”. After a long stay in Prague, they left for Bavaria, Mantua, and Florence where they were received by the Medicis.

Relations between Hossein Ali Beg and Anthony Shirley at this time drastically worsened. In Siena, there was a heavy altercation between the two over the missing presents (for the kings and nobles), with Hossein Ali Beg calling Sir Anthony a thief. On 5 April 1601 the two entered Rome and were greeted with salutes from the Castel Sant’ Angelo, but the two were constantly engaged in a heavy argue over once again precedence, which became so heated that they started lashing out at each other. Due to the conflict, their audience with Pope Clement VIII was delayed. At the end of May of the same year, the two parted. Anthony Shirley left initially for Venice, and later ended his days in Madrid as a pensioner of the king of Spain. Hossein Ali Beg had a different fate, for three members of his group were converted to Catholicism and left the mission as well.

After this happening, which greatly upset him, he continued the journey with the remainder of the group, and was well received by the Spanish court in Valladolid. At the court, he raised an issue which caused some friction, namely regarding the alleged ill treatment of Iranian merchants by the Portuguese authorities on the island of Hormuz. Now that Portugal and Spain were united under one crown, this was also a Spanish matter. King Philip III promised to address the issue and assured that he would continue to fight against the Ottomans with all the means at his disposal. Hossein Ali Beg encountered further issues regarding his group, as the three principal members of his suite, which included his nephew Ali Qoli Beg, were converted by the Jesuits and also become Catholics. His nephew Ali Qoli Beg and Uruch Beg were baptised as Don Philip and Don Juan in the Chapel Royal, with the Spanish King and Queen as sponsors. Hossein Ali Beg, deeply chagrined and unable to do anything, sailed back for Iran from Lisbon in 1602. Hossein Ali Beg and his entourage had also initially made plans to meet with the courts of France, England, Scotland and Poland, but they were abandoned on the way.

Quite the diplomatic mission! By the way, we shall shortly be hearing something about Anthony Shirley’s younger brother Robert, who had stayed in Qazvin to help with training the Persian army.

(The banner image at the head of this post is a Venetian painting of a 1603 Persian diplomatic mission to Venice.)

Catholics subvert, split indigenous Christians of Southern India

There had been Christians in the southern India area of Kerala since the first century CE, as a result of evangelical activity by St. Thomas the Apostle.

This, from English-WP:

The Saint Thomas Christians, also called Syrian Christians of India, Nasrani or Malabar Nasrani… are an ethno-religious community of Indian Christians from the state of Kerala, [some of whom] employ the East Syriac Rite and [some the] West Syriac liturgical rites of Syriac Christianity… Nasrani is an Arabic term for “Christian”. The Saint Thomas Christians had been historically a part of the hierarchy of the Church of the East… They are Malayali people and speak the Malayalam language.

Historically, this community was organised as the Province of India of the Church of the East of Persia by Patriarch Timothy I (780–823 AD) in the eighth century, served by bishops and a local dynastic archdeacon. In the 16th century, as the Church of the East declined.. the overtures of the colonial Portuguese Padroado [archbishopric] to bring St Thomas Christians into the Latin Catholic Church, administered by the Portuguese Padroado Archdiocese of Goa, led to the first of several rifts in the community. The majority joined in full communion with the Holy See in Rome through the Synod of Diamper in 1599, as the Syro-Malabar Church, which is distinct from the Latin Church but is one of the Eastern Catholic churches… The remaining group resisted the Portuguese through the Coonan Cross Oath in 1653, under the leadership of archdeacon Mar Thoma I, and entered into a new communion with the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch..

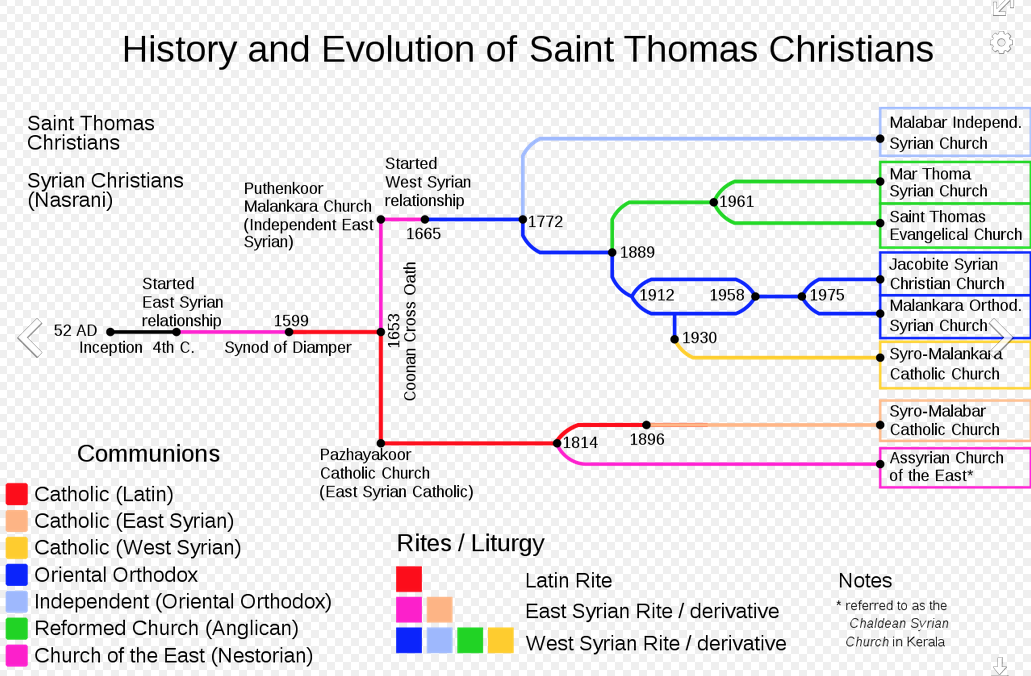

Portuguese-Catholic meddling in the affairs of the Kerala Christians led to centuries of further splits as this diagram shows: