1492? How about 1415 CE?

If we’re trying to identify the start-date of the era of Western domination of world affairs that is now lurching toward a close, then the very serious moves that Portugal made, long before 1492, to build a colonial empire in West Africa and the mid-Atlantic should surely trump the voyage that Spain’s contract explorer Mr. Columbus made in 1492, in which he landed on islands in the Caribbean that he mistakenly thought were “the Indies”.

In most of the popular historiography in the West, Columbus’s “discoveries” of 1492 occupy pride of place, supplemented more recently with 1619, the year in which the first recorded shipload of enslaved Africans disembarked into English-settled Jamestown. But the presence of those enslaved Africans itself bore witness to the role of the long-existing Portuguese trading networks in West Africa that had purchased them there and then shipped them as property over the Atlantic. If we want to understand how “the West” ever emerged as a powerful bloc that came to dominate the affairs of the whole planet, and the nature of the “Western values” that motivated its rise, then the best place to start is the record of Portugal in building a globe-girdling empire in the decades from 1415 on. When Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella sent Columbus off in 1492, they were latecomers to this endeavor, desperate to play catch-up.

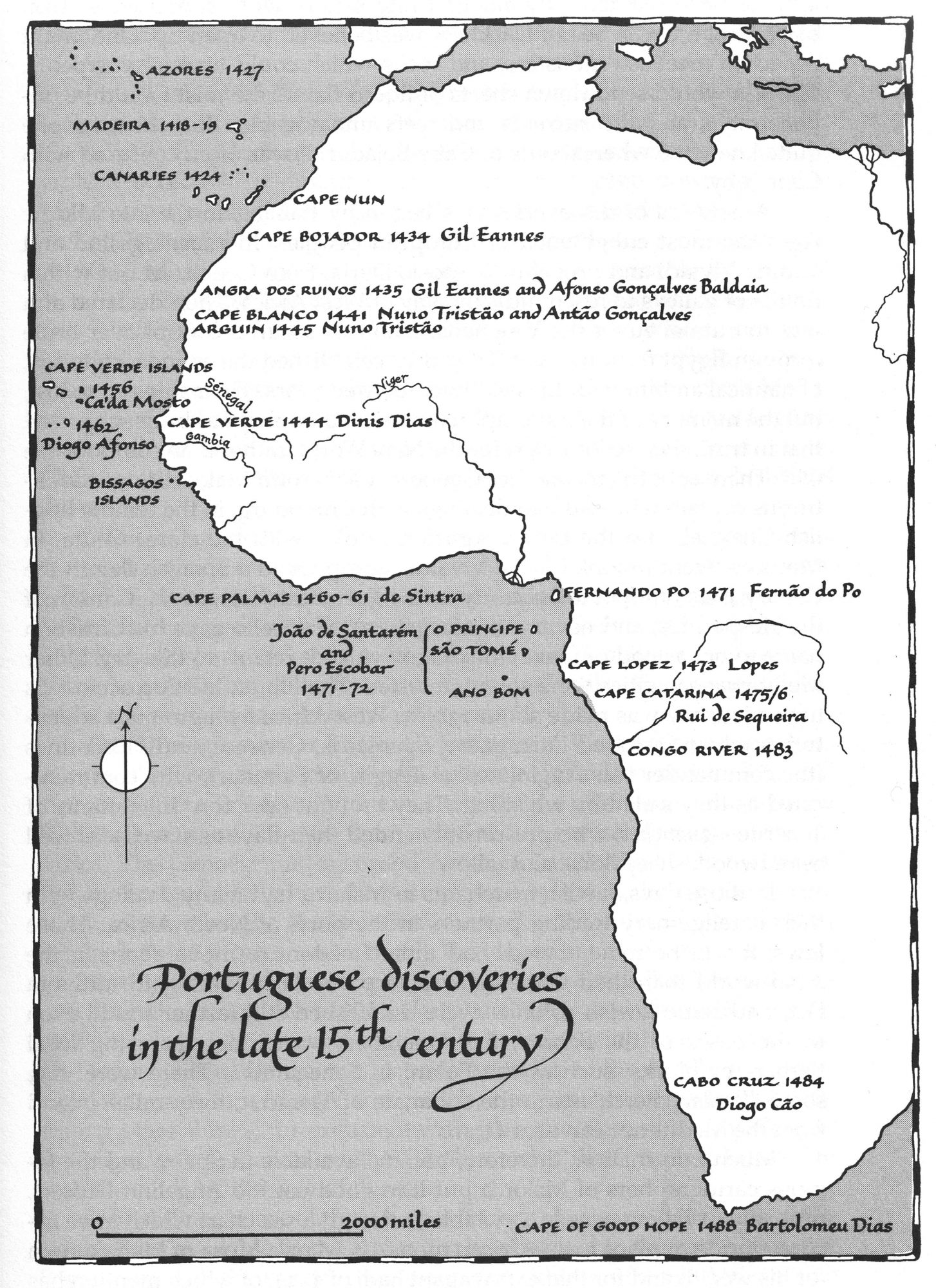

In 1415, Portugal’s king, John I, and his three sons personally led Portugal’s first foray into Africa: the capture of the North African port city of Ceuta. But they didn’t stop there. Over the decades that followed, John and his successors undertook the significant project of every year sending out an (always well armed) naval expedition to “explore” ever further around the Western coast of Africa and to plunder from, or trade on very preferential terms with, the communities they discovered there. Such plunder or enforced trading, from very early on, included the capture, purchase, and exporting of enslaved persons. The Portuguese exploration/plunder raids also poked deep into the Atlantic Ocean, encountering (and seizing control of) a number of archipelagos, including Madeira (1419-20) and the mid-Atlantic Azores (1427).

By 1488, these Portuguese raiding/trading flotillas had reached along the entire, curvy coast of West Africa and had crept around the continent’s southernmost tip at the Cape of Good Hope (Cabo de Bona Speranza.)

They had done this four years before Columbus’s fateful voyage to the Caribbean.

By then, King John II was on the throne in Lisbon. He planned to push the maritime expeditions even further around southern Africa to connect with (and hopefully overpower) the tantalizingly rich civilizations and trading networks that existed beyond it, in and around the whole Indian Ocean. His well-organized networks of spies reported that this might be possible…

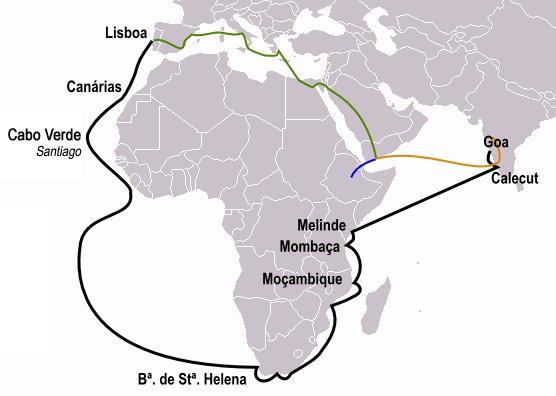

It took time for Portugal’s royal planners to pull together the complex expedition that John II’s dream required. He died in 1495; but his successor, King Manuel, was even more dedicated to the plan, and in 1497 sent out Portugal’s most ambitious expedition yet. The head of this one, Vasco da Gama, was instructed not to hug the whole coast of West Africa but rather, after crossing the equator, to swing to the southwest and use the broadly counter-clockwise wind patterns that previous Portuguese expeditions had identified in the southern Atlantic to blow his flotilla in a broad arc to, and then around, the Cape of Good Hope.

(The banner image above this essay is a painting of King Manuel sending Da Gama’s expedition off from the shore near Lisbon.)

This audacious sailing plan worked. Da Gama’s flotilla rounded the cape, then poked its way up the coast of East Africa as far as Malindi, in today’s Kenya. And from there, using navigational advice given by two Muslim pilots they hired locally, they made their way across the Indian Ocean to Calicut, on the southwestern coast of India.

Over the years that followed, Da Gama and the expedition heads who succeeded him—still always taking the lengthy route around the South Atlantic and the Cape of Good Hope—established well-armed trading posts along much of India’s western coast. Then, the Portuguese pushed even further east: in 1509, a Portuguese navigator reached Malacca, in today’s Malaysia. The Muslim sultan of that strategically located area was unfriendly. In 1511, a follow-up Portuguese expedition returned, captured his fort, and set up a permanent Portuguese fort there in its place. That fort would soon start functioning as the hub of a Portuguese trading network that stretched around the East Indies and across the South China Sea, including to China and Japan.

(Along the way, in 1500, one of the Portuguese captains, sailing the “broad western arc” route to reach the Cape of Good Hope, encountered–and briefly landed on–the coast of today’s Brazil. But he was under strict orders not to tarry. He named the spot the “Land of the True Cross”, claimed it for Portugal, and continued on his way.)

Wherever they went–except, for now, Brazil–the Portuguese captains of that era battled very violently to crush the local trading systems and to leave behind systems, anchored by a string of massive forts, that would ensure continuing Portuguese domination, control–and profits. In 1443, King Afonso V had established the Casa da Guiné, to centralize the organization and administration of all the expeditions he sent out annually from Lisbon. Adventurers and investors from all over Europe flocked to the city to take part in the orgy of ship-building, cannon-casting and -installation, provisioning of ships, and navigating that were needed for the success of these voyages. It was a risky business for everyone involved. Many ships were lost at sea. But the profits could be huge, and the king had bevies of book-keepers in the port to make sure he always got his 20%.

Along the whole of West Africa’s coastline the Casa da Guiné maintained and slowly expanded an extensive and very profitable network of large, fortified warehouses. Their prime function was as pens in which the Casa’s agents gathered their “crop” of enslaved Africans prior to on-shipment. The Casa also extracted some gold and spices from Africa, but the cargoes of enslaved humans rapidly became the staple of its operations there. In The Slave Trade (p.59), Hugh Thomas tells us that by the end of the fifteenth century, Portuguese vessels were shipping 2,000 enslaved persons each year from the fortified warehouses at Elmina and elsewhere in Africa. From 1430 on, the enslaved were imported to, and brutally exploited in, Portugal itself; and sometimes, they were sold from there to other destinations in Europe. Meantime, in the Portugal-seized archipelagos of Madeira, the Azores, and the Cape Verde Islands, the Casa and its associates established a series of plantations that became increasingly reliant on the labor of the enslaved and trans-shipped Africans.

Once Vasco Da Gama and his colleagues had entered the Indian Ocean, the trading networks they encountered there were much denser and more highly developed than those of the West African coast. Traders in this ocean’s ports were dealing–often over very long distances–in fine porcelain, paper, and metal goods from China; in the hyper-profitable “Five Golden Spices” and exotic hardwoods of the Indies; the finely-woven fabrics of India; and the gold, spices, and carvings of East Africa. Many of the peoples of the Indian Ocean’s rim had deep experience and understanding of long-distance navigation, of the complex financial structures needed to support long-distance trade, and of the use and manufacture of gunpowder and sophisticated armaments.

For centuries, prior to 1500, this basin’s waters had been open to whoever wanted to sail in them, though most of its trade networks were dominated by various Muslim dynasties. Attacking those sources of Muslim power and wealth was (along with profit-making) among the goals of the Portuguese as they entered the Indian Ocean…

Portugal, flagship of “the West”

Over the three centuries that followed 1415, four other countries, all perched like Portugal on the Atlantic coast of Europe, also built their own globe-circling empires. Those countries were, in chronological order: Spain, England/Britain, Netherlands, and France. For some brief moments, Denmark and Sweden aspired to join the empire-building trend; and very much later, starting in the late 19th century, Germany, Belgium, and Italy each tried to grab a part of Europe’s world-imperial spoils. But it was the Big Five who collectively built and set the rules for the Western-dominated world system that we still live in today. Later, much later, they were joined by England’s balky step-child, the United States, whose massive, colonially extracted wealth and power dominated the whole system through the decades after 1945.

In my current research and writing project, I’m exploring the origins and early centuries of the West’s domination of the world. In the current phase, I’m looking at each of the Big Five colonial powers in turn, focusing for each on what was new and significant in the way that it set about building (and justifying the building of) its empire. I’m going to look at the Big Five in the order in which they launched their empires. Portugal, being the first, has proven a particularly instructive subject of inquiry.

Roots of Portugal’s emergence

How and why did the small, geographically marginal, and resource-poor country of Portugal burst onto the world scene when it did?

Prior to 1249 CE, there was no such country as “Portugal.” There was none known as “Spain”, either; indeed, there were no entities anywhere in Europe in those days that were recognizable as nation-states in the way we understand such polities today. (One goal of my current project is understanding the extent to which the building of empires was contemporaneous with, and itself helped to spur, the consolidation of nation-states in the polities that built them.)

What there was in the Iberian Peninsula prior to 1249 were geographic areas called variously “Portugal”, “Castile”, “Aragon”, “Leon”, “Galicia”, and so on, each with its own feudal lord. The whole peninsula in that era was a patchwork of distinct (though sometimes inter-marrying), feudal-ish entities ruled over by often competing kings/lords, some of them Catholic and some Muslim. The Catholic church authorities, headquartered somewhat distantly in Rome, were eager to enlist all of Europe’s Catholic rulers in their broad, continuing “Crusade” project to push back the broad influence various Muslim powers had in the Eastern Mediterranean. In Iberia, the Catholic rulers were generally eager to support those campaigns, but they also had their own pressing business in the peninsula, where for several centuries they had been battling in the lengthy project, dubbed the Reconquista, to oust all the local Muslim rulers. And often, the Catholic-Iberian rulers were as eager to battle against each other as against the Muslims. The testosterone-fueled fighting ethos of “knighthood” seemed endlessly to lure them on.

The Muslim armies had first swept up into Iberia in the early eighth century CE, after a conqueror called Tarek Ibn Ziyad shipped a potent fighting force over the narrow strait that separates it from North Africa and proceeded to take huge swathes of land from the then-ruling Visigoths. The massive flow of Muslims up through Iberia into the rest of Europe was halted only in 732, in Poitiers, in southern France. For the next few centuries, nearly all of Iberia was Muslim. Under a string of Muslim princedoms, the area–known to the Arabs as al-Andalous–witnessed a rich Golden Age of arts and learning. But some Catholic feudal leaders from Northern Iberia early on launched their campaign for a “Reconquista”; one of them was the king/lord of Portugal. Those were tough battles, fought over harsh, hard-scrabble terrain and in stormy coastal seas. It was not until 1249 that Portugal’s King Afonso III completed his Reconquista of the whole area in southwestern Iberia that he claimed as his inheritance.

He still had some big battles left to fight–this time against the king/lord of neighboring Castile. But throughout the 14th century, as Christians further east struggled to maintain their “Crusades” against Muslims in the Mediterranean, the Portuguese ruling elite consolidated its hold on the part of Iberia that it ruled, often using an alliance with English lords to counter-balance the growing power of Castile. For its part, Castile had yet to complete its Reconquista from the Muslims of the territory it claimed in Iberia. That would not happen until 1492.

Portugal has a long coastline, all of it west of the Straits of Gibraltar, facing onto the Atlantic. Many of the battles it fought against the Castilians as well as the Muslims were fought at sea. The Portuguese rulers of that era were always acutely aware of the value of–or for them, the necessity of–maintaining strong naval power. But, as English historian Roger Crowley wrote in Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire (p.xxii), “It was Portugal’s fate and fortune to be locked out of the busy Mediterranean arena of trade and ideas.” Thus, while the various kings/lords/doges of Castile, Aragon, France, Genoa, and Venice were forced to engage deeply in the politics, commerce, and wars of the Mediterranean, Portugal was under no such pressure. Indeed, from its earliest days as an independent polity the country’s leaders judged that gaining alliances, access, and profits from lands in the Atlantic and beyond was essential to the survival of their nation-building project. Hence, the longterm alliance they maintained with England. And hence, the intense focus successive Portuguese kings gave, from 1415 on, to supporting the series of large maritime raiding/trading expeditions whose preparations required a stunningly large proportion of the emerging nation’s available income.

Between 1442 and 1456, as those expeditions started reaching ever further around Africa’s western coast, a series of decisions were taken that gave added impetus to the empire-building project:

- In 1442 in Rome, Pope Eugene IV granted a “plenary indulgence” to the knights and friars of the Order of Christ, a religio-political fighting body headed by Portugal’s charismatic Prince Henry (also known as “the Navigator”), that was very involved in Portugal’s expeditions in the Atlantic. The “plenary indulgence” was basically a free pass from any church sanction on any brutal or larcenous activities that members of the order might commit while “on mission.”

- In 1443, as already noted, King Afonso V established the Casa da Guiné, to centralize the organization and administration of the expeditions sent out annually from Lisbon.

- In a linked move in 1443, the Portuguese Regent gave Prince Henry monopoly rights “to explore, make war, and trade” in all parts of West Africa’s Cape Bojador region.

- In 1452, a new pope, Nicholas V, issued a new “Papal Bull” (decree) called “Dum Diversas” in which he granted to Afonso V “full and free permission to invade, search out, capture, and subjugate the Saracens and pagans and any other unbelievers and enemies of Christ wherever they may be, as well as their kingdoms, duchies, counties, principalities, and other property […] and to reduce their persons into perpetual servitude.” That was the Catholic church’s first authoritative and open articulation of support for a policy of seizing lands from non-Christians all around the world and of imposing perpetual enslavement on the inhabitants of those lands.

- In 1453, a vigorous new Muslim power in the Eastern Mediterranean, the Ottoman Empire, successfully captured the longtime capital of Eastern Christianity, Constantinople (Istanbul.) The strength of this new Muslim power sent shock-waves throughout Christian Europe. It also sent many of the financiers, shipbuilders, merchants, and skilled artisans who had built the power of East-Mediterranean city-states like Venice and Genoa fleeing westward. As Crowley noted in his book, many of those ended up in Lisbon.

- The emergence of Ottoman power–which soon thereafter started sweeping into Europe’s landmass from the east–also provided the context in which yet another new pope, Calixtus III, reaffirmed the powers that Dum Diversas had given to the Portuguese, which he did with new Bulls issued in 1455 and 1456.

Portugal and the dawn of West-European slavery systems

One of the earliest recorded instances of Portuguese captains shipping captive Africans to Lisbon occurred in 1441, when Antão Gonçalves carried twelve Africans whom he seems to have bought from slave traders in Cabo Branco, back to “show” them to Prince Henry (Hugh Thomas, pp. 54-55.) What happened to the Africans after being thus displayed was not recorded. For a few years after that, as Gonçalves and his Portuguese colleagues pushed their expeditions ever further along the African coast, they tried to circumvent the local slave-traders in West Africa and would launch their own hit-and-run raids to capture, enslave, and trans-ship the indigenous Africans. In later decades, as the Portuguese presence around West Africa became more institutionalized through the building and staffing of armed trading stations (feitorias), the Portuguese officials running these feitorias reverted to buying their cargoes of enslaved from the local traders, who were often Muslim holy men.

Prince Henry died in 1460. For a while after that the Portuguese royals were less interested in the African project and left it to private Portuguese traders to push it forward. In 1471 one such trader was the first to reach the coast of today’s Ghana, then the hub of a thriving gold trade. He established a small trading post at a spot there called Elmina. Ten years later, John II, came to the throne in Lisbon. A big supporter of all Portugal’s imperial projects, he decided to invest in building a large, well fortified trading hub at Elmina. In 1482, he sent down a royal fleet that carried all the needed building materials for this fort, many in easy-to-assemble, prefabricated form. The local ruler, Kwamin Ansah, was reportedly open to Portugal continuing to have a regular-style trading station–but not a large, stone-built fort! Portuguese commander Diogo de Azambuja proceeded with his instructions regardless, burning the whole of the local village in the process.

After building the fort, he declared Elmina to be an independent state under Portugal’s over-all sovereignty (A.R. Disney, pp.57-58.) It speedily became the most important embarcation zone for Portugal’s prolific trans-Atlantic slave-shipping operation.

A Portuguese chronicler of the 15th century called Zurara wrote that between 1441 and 1448, a total of 927 enslaved Africans slaves were brought to Portugal; but from then on, the numbers soared, with an estimated 1,000 enslaved Africans arriving in Portugal each year. After 1490–that is, after Azambuja’s fort at Elmina was in full operation– that number doubled.(Quoted at this spot in Wikipedia.)

Through its exploits in West Africa in the 15th century, Portugal was the “pioneer” among West Europe’s still-emerging nation-states in developing the purchase and transoceanic shipment of enslaved Africans. Over the centuries that followed it would retain its role as the world leader. Between 1500 and 1875, Portugal is estimated to have embarked 5.8 million captive Africans on its trans-Atlantic slave ships, out of a Europe-plus-USA-wide total of 12.5 million embarked.

Competition from Spain, and Columbus

One of the people who reportedly sailed down to Elmina on a Portuguese vessel–possibly even on Azambuja’s fateful expedition–was the Genoese adventurer Christopher Columbus. Columbus had been living in Lisbon since 1477, working as a merchant on long-distance sea-routes on behalf of a rich Genoese family. In 1484 and again in 1488, he had an audience with Portugal’s King John II in which he presented his plan to find a workable westward sea-route to East Asia’s long-fabled Spice Islands of the “Indies”. Both times, John turned him down. In 1486, Columbus took his plan to Queen Isabella of Castile. Her experts, like King John’s, judged his geography and his navigational plans incorrect, and she refused to back it. England’s Henry VII also turned him down. Finally, in April 1492, just weeks after Isabella and her spouse King Ferdinand of Aragon had finally completed the Reconquista of their home territory by capturing Granada, Ferdinand persuaded Isabella to give the plan a try. Columbus set off speedily, in early August, and two months later was the first European to sight land in the Caribbean. On that first voyage, he made landfall in the Bahamas and in today’s Cuba and Haiti.

I’ll write more later about Columbus’s voyage and the era it ushered in, in which a whole new globe-spanning empire was built by the “the Catholic Monarchs of Spain”, as Ferdinand and Isabella were known. For now, I’ll just note that on his return voyage to Spain, Columbus took with him a collection of Indigenes whom he had captured from the Caribbean islands; his ship was blown off course and he had to make landfall in Lisbon, where his display of his captives gave incontrovertible proof that he had “discovered” an entirely new set of lands and cultures who were clearly not African (and whom, then and thereafter, he still judged to be “Indios”.)

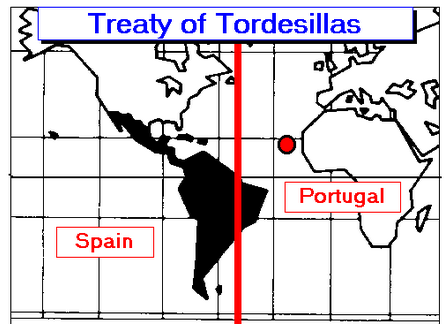

King John was outraged. Thirteen years before, he and his father had concluded a treaty with Ferdinand and Isabella, which ended a lengthy Portuguese-Spanish war on the basis that Spain would retain what it held on land, while Portugal would retain what it held in the Atlantic–that is, everything in the known-to-Europeans Atlantic except the Canary Islands, which Spain had held since 1402. He fired off a furious letter to the Spanish monarchs, accusing them of violating that treaty. There followed several months of accusations and counter-accusations. Finally, in September 1494, the two sides concluded a new treaty, the Treaty of Tordesillas, in which they agreed to split the Atlantic and the lands bordering it to the west and south along a line that ran North-South roughly halfway between the Cape Verde Islands, already held by Portugal, and the new lands encountered by Columbus in the Caribbean. (Columbus, meanwhile, had set off on his even more extensive second voyage to the Caribbean.)

The Treaty of Tordesillas was speedily ratified by the Pope. The earlier papal edict “Dum Diversas” that granted to Portugal the right “to invade, search out, capture, and subjugate the Saracens and pagans and any other unbelievers and enemies of Christ wherever they may be […] and to reduce their persons into perpetual servitude” remained in force; and the Spanish monarchs simply assumed that they, too, could apply the permission to conquer and enslave that it granted in the lands they planned to enter in the Americas, too.

The line agreed at Tordesillas allotted to Portugal the portion of Eastern South America that would become Brazil, as well as the entire coast of West Africa and all lands to the east of that. As we shall shortly see, once Portugal’s royal empire-builders decided to start establishing large plantations for sugar and other commodities in Brazil, they found it very straightforward to ship large numbers of enslaved Africans to those plantations from the slavetrading posts they had already built in West Africa.

But after Tordesillas, as Columbus and the Spanish conquistadors who followed him plundered and ravaged their way through the Caribbean and the non-Brazil portions of the American mainland, they still could not participate directly in the extraction of enslaved persons from Africa. They did engage, however, in widespread enslavement campaigns on their own account, capturing the Native peoples they encountered in the Caribbean and the American mainland and forcing them to work in the plantations and mines they established there. They also trans-shipped large numbers of these enslaved between their various settler-colonial holdings in the New World. And then, when they had worked some of these Indigenous enslaved literally to death, Portuguese merchants were always eager to sell them large shipments of enslaved Africans…

Portugal, the Indian Ocean, and Islamophobia

According to Roger Crowley, the new king crowned in Lisbon in 1495, Manuel, “inherited a strong streak of messianic destiny that ran deep in the Portuguese royal house of Aviz.”(p.30) It was a time, as the year of 1500 CE approached, of much popular messianism in Christian Europe. And Manuel judged that his name itself–“Emmanuel: God with us”–was a special sign.

Crowley wrote (p.31),

The India plan, which had faltered in the later troubled years of [John’s] reign, became the primary outlet for these dreams. Manuel believed he had inherited the mantle of his granduncle Henrique, ‘the Navigator.’ Since the fall of Constantinople, Christian Europe had felt itself increasingly hemmed in. To outflank Islam, link up with Prester John [a Christian king who was rumored to rule somewhere in Africa] and the rumored Christian communities of India, seize control of the spice trade, and destroy the wealth that empowered the Mamluk sultans in Cairo–from the first months of his reign, a geostrategic vision of vast ambition was already in embryo; it would, in time, sweep the Portuguese around the world.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, most of Europe was still a pretty impoverished and technically backward place. Many areas were still reeling from the after-effects of the Black Death. The richest portions of the continent were coastal city-states of today’s Italy such as Venice, Genoa, or Ravenna; and much of the wealth of those polities derived from the long trading and banking relationships they had developed with the great cities and countries of Islam. Those Italian city-states sat, indeed, at the European terminus of the famed “Silk Road”, which was never a single road but rather a network of land and sea routes that brought to Europe and North Africa several notable products and technologies from the distant–and often technologically much more advanced–lands of Asia. Westward along this Silk Road, over the centuries, had come knowledge of gunpowder, paper-making, and moveable type. Along it came fine fabrics and the products of advanced metallurgy. Along it came peppercorns and the other fine spices that could help cooks to preserve meats for much longer and to enhance diets of otherwise tedious monotony.

But the whole Silk Road, both by land and by sea, was under Muslim domination. The longheld desire of Christian rulers in Europe to find a way to travel directly to “the Indies” was not just a desire to make profits from importing those muslins and spices on their own account. It was also a way to break the economic power of the Muslim world.

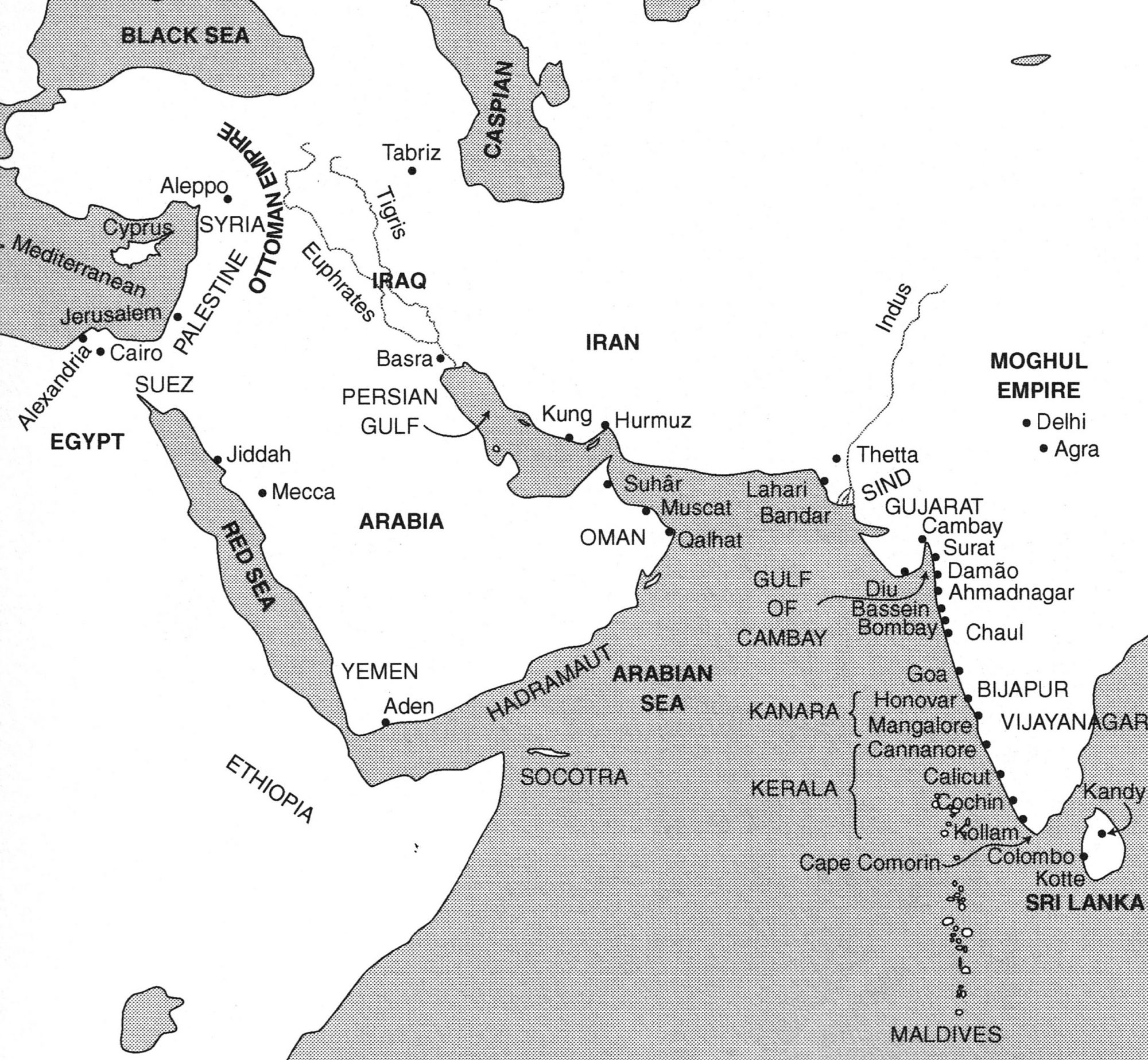

One of the most brutal (and most successful) of the leaders of Portugal’s empire-building venture in the Indian Ocean, Afonso de Albuquerque, was unabashed in describing the anti-Muslim goals of his work. Albuquerque was a seasoned military man, born around 1453, who had earlier served ten years in Portugal’s army in North Africa. He had fought against the Ottomans–and against the forces of Castile–and had headed King John II’s land forces. In 1503, King Manuel appointed Albuquerque co-head of Portugal’s large annual naval expedition to India. After returning to Lisbon, he stayed on a while to help Manuel with his strategic planning for India. In 1506, he was again sent out with the annual sailing to India. This time, the mission of his sub-group was to conquer the island of Socotra, off the south coast of Yemen, and to build a fortress there that could strangle all sailings in and out of the Red Sea, cutting off the direct access that heartland Muslim cities like Cairo, Mecca, and Jeddah had long enjoyed to the Indian Ocean trade routes. He speedily captured Socotra and built a fort there, but instead of staying there he then headed east and undertook a brutal rampage against the port cities of today’s Oman, ending up at Ormuz (Hormuz.) That strategically located island city was under the suzerainty of Persia’s Safavid Empire. Given that the Safavids were in a deep and longheld religio-political struggle against the Sunni Muslim Mamluks who ruled Egypt, Albuquerque’s swing to Ormuz, was not just a diversion but also a big strategic error.

Albquerque did not get back to his Red Sea task until 1513. In the meantime, operating as Governor of Portuguese India, in 1510 he had captured and fortified the West-India city of Goa, which would remain in Portugal’s hands until 1961… And in 1511, he was the one who conquered Malacca.

When he returned to the Red Sea in 1513, his new objective was the well-defended port of Aden. He was unable to capture it, but he then took his flotilla through the Bab al-Mandeb strait and into the body of the Red Sea. Twelve hundred miles to the north lay the port city of Suez. He and his Portuguese colleagues had long feared that Cairo’s “Mamluk” Muslim rulers were preparing a large armada there that might sail down the Red Sea and attack the Portuguese positions in the Indian Ocean. He wanted to rout that feared Muslim fleet. But his ambitions, and those of his monarch, were much greater. Crowley told us (pp. 298-99) that Albuquerque he wrote to Manuel:

Great tranquillity and stability have come over India since Your Highness… ordered us to enter the Red Sea, seek out the Sultan’s fleet and cut the shipping lanes to Jeddah and Mecca… It is no small service that you will perform for Our Lord in destroying the seat of perdition and all their depravity.

This was a clear allusion to a plan to overthrow Muslim rule in its Arabian heartland.

Albuquerque still seemed to have only sparse information about these regions in which he was operating. The Mamluk Sultan had indeed tried, a few years before, to pull together a fleet in Suez to send against the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean, but had been notably unsuccessful in doing so. Also, Albuquerque and the other Portuguese had finally identified the Christian king of Ethiopia, which then bordered the southwest coast of the Red Sea, as the actual “Prester John” they had been searching for for so long, and they had been hopeful that this monarch, endowed with his storied riches and large armies, could significantly help their campaign against Cairo and Mecca. But far from being able to provide decisive military help to the Portuguese, the Ethiopian needed a lot of military help from them in order to hang onto power at home.

Albuquerque was also deeply unprepared for the harsh conditions of the Red Sea. Once he entered the sea, he found it very hard to find enough fresh water to keep his crews alive. After a few months waiting around in the southern end of the sea, he sailed back to Goa.

Albuquerque died near Ormuz in 1515. He had never directly confronted the Mamluks who ruled Egypt; but his entry into the Red Sea in 1513 sent shock-waves through Cairo that helped bring about the collapse of the Mamluk Sultanate four years later. It was not, however, any Christian power that supplanted them in Egypt and Arabia. It was the Ottomans.

Another Spanish surprise

Throughout the decades after the 1511 seizure of Malacca, the Portuguese Crown continued–in its now-customary collaboration with private investors–to extend the trading empire it was building up all around the Indian Ocean. The crucial intellectual property it amassed on those expeditions were the “roteiros“, the logbooks in which the Portuguese captains recorded all the details, both navigational and commercial, of their voyages. These roteiros were closely guarded from all foreign powers, and from the eyes of the many non-Portuguese who sailed on the Portuguese ships.

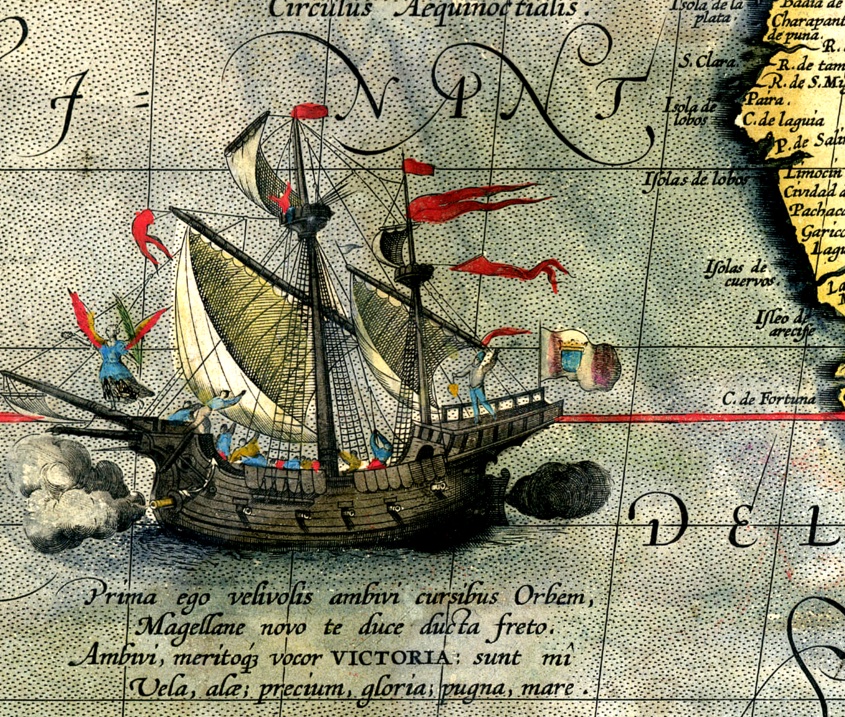

It was, however, a Portuguese navigator/fighter who would undertake the greatest treachery of all against the country’s Asian-imperial trade secrets. That was Fernão de Magalhães (Ferdinand Magellan), who had sailed with Albuquerque to Malacca but later fell out of favor with the nabobs of Portuguese adventuring. In 1517, Magellan traveled to Spain and persuaded a new young king there to back an expedition to sail to the East Indies by taking the previously untested route westward around South America. He set out from Spain in September 1519, sailed around the tip of South America, and in early 1521 made landfall on an island in the east of today’s Philippines, which he claimed for Spain.

Once again, the Portuguese were furious at Spain’s success. And once again, after lengthy arguments, there was a negotiation over how to divide the distant lands the rival Iberian empires claimed. In 1529, they reached the Treaty of Zaragoza, which drew a North-South line of demarcation between what the two empires could rule (or claim) in the East Indies, that complemented the line drawn down the Atlantic at Tordesillas. This time, they did not even bother to seek Papal ratification.

Portugal institutes settler colonialism in Brazil

By the end of the 1520s, it had become clear to the Portuguese that their neighbors/competitors in Spain were able to generate staggeringly high profits from the brutal form of settler colonialism they were instituting in the Americas, which was based both on resource-extraction and on setting up slave-powered plantations to grow and process the sugar then coming into vogue in European markets. So the Portuguese started to look at the possibilities for such activities in the portion of South America that Tordesillas had allotted to them. One of the first significant resources they identified in that land was brazilwood, long known for its strength and as a source of a red dye. There were also rumors (as so often) of rich deposits of silver and gold in the interior. In 1534, King John III started to establish a system of full-blown settler colonialism in that part of South America, which thereafter became known as Brazil (after the wood.) The scheme he instituted had already been well developed by the Portuguese in the Atlantic islands of Madeira, the Azores, Cape Verde, and Saõ Tomé. He divided the land of Brazil into 16 strips running east-west and made land grants for each of them to his favorites among the minor nobility and the retired military.

Of those 16 original “captaincies” in Brazil, only a couple proved profitable. One was Pernambuco, whose founding captain, Duarte Coelho Pereira, had fought in Portuguese campaigns in East Asia and married into the family of Afonso de Albuquerque. The other was São Vicente, in the south, whose founding captain, Martim Afonso de Sousa, was a buddy of the king. (After succeeding in São Vicente, De Souza went on to be governor of Portuguese India in the 1540s. Portugal’s major imperial projects had many such linkages.)

Significantly, both those Brazilian “captains” succeeded because they made large-scale investments in establishing slave-powered sugar plantations. In the early years, they were able to capture and exploit as many thousands of enslaved Indigenes as they needed for those projects, but by the end of the 16th century they were also importing significant numbers of enslaved people shipped in from Africa.

For the Portuguese empire-builders, in Brazil as elsewhere, Christianizing the “natives” was always part of their plan. To some degree this may have been performative, that is, as a way to reassure themselves and other European Catholics of the moral value of their project (though the means they used to do the Christianizing were often horrifically violent.) But in the Americas, the Portuguese had concluded–as the Spanish also had–that some of the structures and practices of the Catholic church could help them win their twin goals of exploiting while controlling the natives. While the Spanish used mainly the well-established monastic orders of the Dominicans, Augustinians, and Franciscans to do this, the Portuguese worked closely with the leaders of the newly formed “Society of Jesus” (Jesuits), instead. In Brazil, the Jesuits established a whole network of strategic hamlets, which they they called “Reductions,” into which the Native communities were forcibly relocated, and where they came under the constant control of the Jesuit Fathers. The Jesuits also helped to “pacify” the Tamoio Indigenes in the south, though t is hard to discover how they did that.

Throughout the 16th century, the Portuguese settlers in Brazil faced continuing resistance from the Native peoples. In 1548, the boss of the Bahia captaincy and all the settlers he had brought in were killed by the Indigenes. In 1556, the first bishop sent to Brazil, Pero Fernandes Sardinha, was killed and eaten by Caeté natives after he landed in their area after a shipwreck. But by the 1570s, a series of ferocious Portuguesee military raids in key regions had reduced the resistance to a manageable level…

Succession crisis in Lisbon

In 1557, King John III died and was succeeded by his 3-year-old grandson, Sebastian. A series of regents ruled until Sebastian was 14 years old, at which he point he took over. (Much of his education was provided by the Jesuits.) In 1576, a sharp succession struggle erupted between rival Muslim dynasties in the interior of Morocco, where Portugal had retained several coastal enclaves after its original capture of Ceuta in 1415. Sebastian saw a big chance to intervene and to realize the long-held Portuguese dream of capturing all of Morocco. In August 1578 he assembled a force of some 23,000 men with 40 cannons and led them over to Morocco. He had the active support of nearly all of Lisbon’s ruling elite, many of whom came on the campaign with him.

They joined battle against the forces of the pro-Ottoman faction in Morocco at a place called al-Qasr al-Kbir. It was a rout. Four hours of fighting left 8,000 Portuguese dead, including Sebastian and almost the whole of the Portuguese nobility. The other 15,000 Portuguese fighters were captured and sold into slavery. Sebastian’s body was never found.

This was the deepest crisis Portugal’s monarchy ever faced. Next in line in Lisbon was Sebastian’s great-uncle Henry, who immediately took over. But Henry was a cardinal, so he couldn’t assure a stable succession. He asked the (as it happened, pro-Spanish) Pope if he could leave the priesthood to get married. The Pope refused. Two years later, Henry died. Numerous distant relatives had some tenuous claim to the Portuguese throne. One stepped forward and proclaimed himself king. But the Spanish contested his claim and assembled a fighting force of 40,000 men to prevent his coronation.

Portugal’s own army was still in tatters. In August, the Spanish force entered Lisbon. Spain’s King Philip II convened a special session of the Portuguese Cortes (parliament) which proclaimed him as King Philip I of Portugal. For the next 80 years, the two countries were ruled by a single (Spanish) monarch.

Throughout those decades, the fact of Spain’s control of Portuguese decisionmaking, as well as the crushing blow Portugal’s political elite had suffered at al-Qasr al-Kbir, left the central organizing bodies of the Portuguese empire rudderless. As we shall see, during the 60-year period of this “Iberian Union” private Portuguese interests and a whole array of actors from other European countries started to impinge on the broad trading, slavetrading, and settler-colonizing empire that the Portuguese Crown had built up since 1415…

Portugal’s empire-building through 1580

1580 is a useful point at which to pause and review the “achievements” of the first 165 years of Portugal’s world empire, the first of the “Big Five” of the global empires built by West-European nations:

- Though Castile/Spain had captured and started settling the Canary Islands off the northwest coast of Africa as early as 1402, in 1415 Portugal was the first European power to capture, garrison, and hold land on the North African mainland.

- Portugal thereafter used its significant maritime and amphibious fighting abilities to despatch armed raiding/trading vessels to increasingly distant points around the West African coast, at some of which it overcame local opposition and pioneered the establishment of armed trading fortresses.

- The Casa de Guiné rapidly found that enslaved Africans would form a profitable and increasingly large part of what they seized or purchased from those African trading forts.

- The enslaved Africans could be sold in Europe or could very profitably be exploited in the plantations the Portuguese developed in the Atlantic archipelagos they had captured and occupied. These plantations formed a prototype for what Spain and other imperial powers would later develop in, first, the Caribbean, and later the North American mainland–and also, for the plantations Portugal itself would develop in Brazil.

- This whole empire-building project required the establishment of a complex series of institutions in the home-port of Lisbon, to ensure the continued financing, building, arming, provisioning, and expert navigation of the annual fleets, and the onward marketing and distribution of all the “fruits” of empire. Lisbon rapidly developed into a wealthy, technologically advanced metropolis.

- Once Vasco da Gama had successfully entered the Indian Ocean, Lisbon became directly plugged into the richest trading zone the world had ever seen.

- Until then, the seas of that whole basin had been “open” to all interested navigators and traders. The Portuguese aimed to make it into a mare clausum (closed sea) in which they would monopolize control of all the significant trading ports. They succeeded, to a remarkable degree. That success depended centrally on their ability to deploy extremely brutal force, and their demonstrated readiness to use it.

- In continental Africa and around the shores of the Indian Ocean they did not, in this period, seek to exercise direct control over large areas of land. Instead, through the size, sturdiness, and intimidating capabilities of the trading forts they established they sought to dominate the local societies and force Lisbon’s trading terms on them.

- In Brazil, Portugal was more a follower (of the example set by Spain in the Americas) than a leader. It established an extensive settler-colonial project that would control large areas of land and all the inhabitants and resources thereof, while also bringing in–and allocating land to–significant numbers of home-country settlers and trying to build an entire, Portuguese-dominated society there.

- In all these phases of its empire-building, the Portuguese were pursuing an explicitly Catholic-Christian agenda alongside their continued pursuit of profit. In Africa and the Indian Ocean, the Christianizing was tightly tied to a harsh anti-Muslim agenda. In Brazil, the Christianizing was pursued as a means of exercizing control over the Indigenous population; and one Portuguese “innovation” in this approach was the use of the Jesuits and their hyper-disciplined strategic-hamlets system.

An earlier explorer in the Indian Ocean

It seems timely to note that the approach the Portuguese adopted to the trading systems, rulers, and peoples they encountered in the Indian Ocean was not the only approach they might have pursued there.

Ninety-three years before Vasco Da Gama entered the scene, China’s Ming Dynasty had looked set to enter the Indian Ocean’s trading system in a big way. Every three years from 1405 on, China sent a massive naval expedition around the coast of the whole ocean, “from Borneo to Zanzibar,” under the command of a Muslim admiral called Zheng He. At the center of each of his fleets were multi-decked treasure ships called “star rafts”, each 440 feet long, with nine masts. Each fleet carried enough food for a year; they navigated straight across the Indian Ocean from Malaysia to Sri Lanka, with the aid of compasses and closely calibrated navigational charts. Roger Crowley has written of these expeditions that, “Although they had ample capacity to quell pirates and depose monarchs and also carried goods to trade, they were primarily neither military nor economic ventures but carefully choreographed displays of soft power. The voyages of the star rafts were nonviolent techniques for projecting the magnificence of China to the coastal states of India and East Africa.” (Crowley, Conquerors, p. xx.)

Then, in 1433, a new Chinese emperor, who seemed more concerned about the terrestrial threats from China’s northern neighbors than about projecting power into the Indian Ocean, abruptly ended the star-rafts project. As Crowley noted, “Oceangoing voyages were banned, all the records destroyed.” In 1498, when Da Gama arrived in the Indian Ocean in his very much smaller vessels, he met no Chinese star rafts. It is interesting to speculate on how global history might have been different if he had.