Two big developments in the history of Western imperialism in 1685 CE. France’s Louis XIV introduced his infamous ‘Code Noir’ to regulate treatment of the enslaved (and exclusion of Jews) from France’s colonies, in the Caribbean and elsewhere. And in England, King Charles II died; his very Catholic (and slave-trading) brother James took over, but was immediately challenged by an armed, Protestant uprising led by Charles’s illegitimate son.

The shenanigans in England’s royal family may seem like a niche interest, but to me one of the interesting issues is how those shenanigans and the parallel contest between the royals and the parliament interacted with– and perhaps even helped to spur?– England’s almost uninterrupted pursuit of its imperial project.

Also of note: It was not only in England that Catholic-Protestant tensions were still rife. In France, 1685 also saw Louis XIV revoking the 1598 Edict of Nantes that had guaranteed freedom of worship to Protestants, known in France as Huguenots. That move also had reverberations in the colonies.

Anyway, today we’ll go first to France then to England.

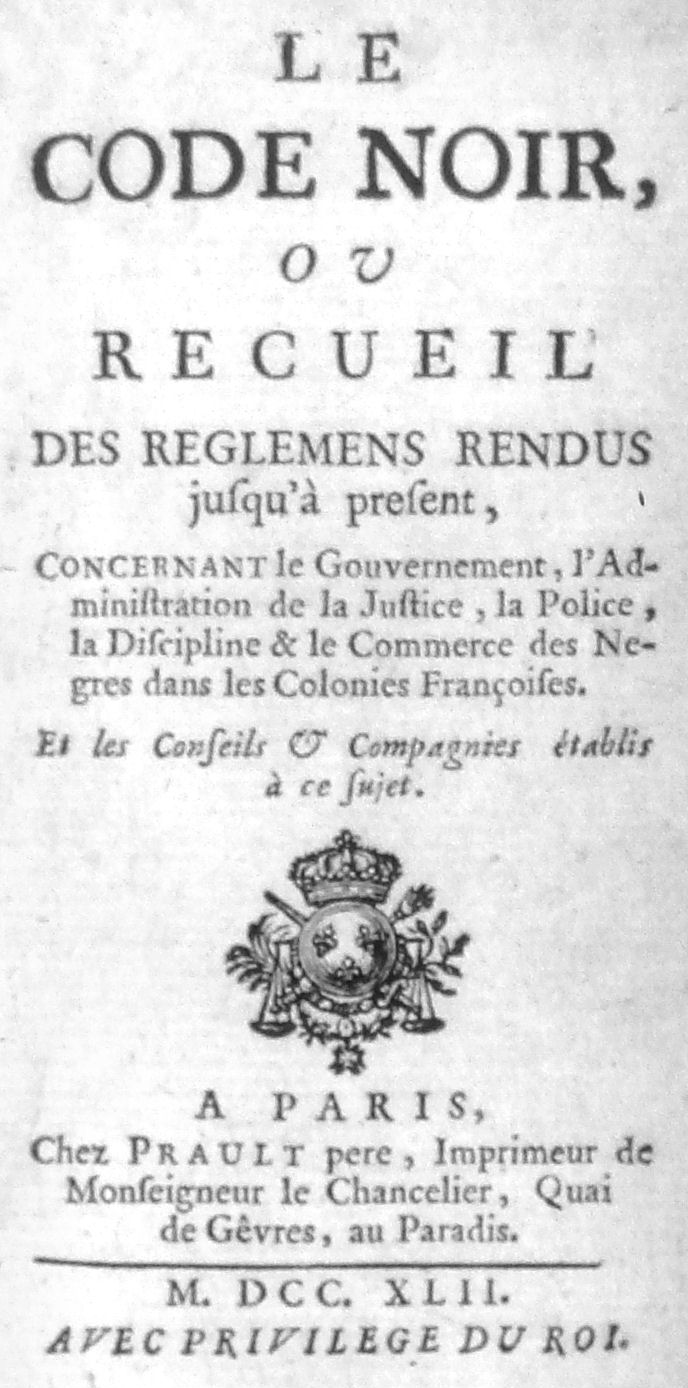

France passes ‘Code Noir’, cracks down on Jews and Protestants

This page on Wikipedia tells us that as far back as 1315 CE France had had a ban on having any enslaved persons in France itself. But during the 17th century France had seized Martinique, Haiti, and other islands in the Caribbean where there were, as we know, large profits to be made if they could be used for sugar-cane plantations as part of the Atlantic’s brutal “Triangular Trade”… But of course that required the widespread exploitation of enslaved laborers there in the Caribbean.

In 1681, Louis had charged his powerful Prime Minister Jan-Baptiste Colbert with creating a legal framework to regulate the institution of slavery in the French colonies. Colbert died in 1683 and the task was completed by his son, also Jean-Baptiste Colbert.

In the Caribbean at the time, that same page on WP tells us, Indigenous people “had French status with the same rights as French people, although only after their baptism into the Catholic religion. It was forbidden to enslave them.” That latter prohibition was in marked contrast to the way the Spanish, English, and Dutch treated Indigenous people in their colonies. I wonder if the French prohibition was enforced? Also, what about the Indigenous people who refused baptism?

Anyway, WP also tells us this:

The Code aimed to provide a legal framework for slavery, to establish protocols governing the conditions of inhabitants of the colonies, and to end the illegal slave trade. Religious morals also governed the crafting of the Code Noir; it was in part a result of the influence of the influx of Catholic leaders arriving in Martinique between 1673 and 1685.

The Code had 60 articles. Here were its main provisions, as listed in WP:

Rules about religion

- Jews could not reside in the French colonies (art. 1)

- Slaves must be baptized in the Roman Catholic Church (art. 2)

- Public exercise of any religion other than Roman Catholicism was prohibited; masters who allowed or tolerated it by their slaves could also be punished (art. 3)

- Only Catholic marriages would be recognized (art. 8)

Rules about sexual relations and marriage

- Children of a female slave and a free man:

- If the father was unmarried, he should marry the slave concubine, thus freeing her and her children from slavery

- Otherwise the punishment would be a fine for both the father and the slave’s master. The fine was 2000 pounds of sugar (art. 9)

- If the father was the slave’s master, in addition to the fine, the slave and any resulting children would be removed from his ownership, but not freed (art. 9)

- Weddings between slaves strictly required the master’s permission (art. 10) but also required the slave’s own consent (art. 11)

- Children born to married slaves were also slaves, belonging to the female slave’s master (art. 12)

- Children of a male slave and a free woman were free; children of a female slave and a free man were slaves (art. 13)

Prohibitions

- Slaves must not carry weapons except under permission of their masters for hunting purposes (art. 15)

- Slaves belonging to different masters must not gather at any time under any circumstance (art. 16)

- Slaves should not sell sugar cane, even with permission of their masters (art. 18)

- Slaves should not sell any other commodity without permission of their masters (art. 19–21)

- Masters must give food (quantities specified) and clothes to their slaves, even to those who were sick or old (art. 22–27)

- (unclear) Slaves could testify but only for information (art. 30–32)

- A slave who struck his or her master, his wife, mistress or children would be executed (art. 33)

- A slave husband and wife and their prepubescent children under the same master were not to be sold separately (art. 47)

Punishments

- Fugitive slaves absent for a month should have their ears cut off and be branded. For another month their hamstring would be cut and they would be branded again. A third time they would be executed (art. 38)

- Free blacks who harboured fugitive slaves would be beaten by the slave owner and fined 300 pounds of sugar per day of refuge given; other free people who harboured fugitive slaves would be fined 10 livres tournois per day (art. 39)

- If a master had falsely accused a slave of a crime and as a result, the slave had been put to death, the master would be fined (art. 40)

- Masters may chain and beat slaves but may not torture nor mutilate them (art. 42)

- Masters who killed their slaves would be punished (art. 43)

- Slaves were community property and could not be mortgaged, and must be equally split between the master’s heirs, but could be used as payment in case of debt or bankruptcy, and otherwise sold (art. 44–46, 48–54)

Freedom

- Slave masters 20 years of age (25 years without parental permission) may free their slaves (art. 55)

- Slaves who were declared to be sole legatees by their masters, or named as executors of their wills, or tutors of their children, should be held and considered as freed slaves (art. 56)

- Freed slaves were French subjects, even if born elsewhere (art. 57)

- Freed slaves had the same rights as French colonial subjects (art. 58, 59)

- Fees and fines paid with regard to the Code Noir must go to the royal administration, but one third would be assigned to the local hospital (art. 60)

WP also says this about the ratification and application of the Code:

It was ratified by Louis XIV and adopted by the Saint-Domingue sovereign council in 1687 after it was rejected by the parliament. It was then applied in the West Indies in 1687, Guyana in 1704, Réunion (in the Indian Ocean) in 1723, and Louisiana in 1724…

In Canada, slavery received legal foundation from the king from 1689 to 1709. The Code Noir was not intended for or applied in New France’s Canadian colony. In Canada, there never was legislation regulating slavery, no doubt because of the small number of slaves. Nevertheless, the intendant Raudot issued an ordinance in 1709 that legalized slavery

The fact that the very first article was a prohibition on Jews residing in the French colonies was fascinating. Indeed, in those years Louis was clearly heading in an intolerant Catholic-supremacist direction, as he had shown for several years before 1685. But he displayed his intolerance most clearly in October that year when he passed the Edict of Fontainebleau, which revoked the guarantees of freedom of religion that France’s “Edict of Nantes” had long given to the country’s Huguenots.

The WP page on the Edict of Fontainebleau tells us this:

By the Edict of Fontainebleau, Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes and ordered the destruction of Huguenot churches as well as the closing of Protestant schools. The edict made official the policy of persecution that was already enforced since the dragonnades that he had created in 1681 to intimidate Huguenots into converting to Catholicism. As a result of the officially-sanctioned persecution by the dragoons, who were billeted upon prominent Huguenots, many Protestants, estimates ranging from 210,000 to 900,000, left France over the next two decades. They sought asylum in the United Provinces, Sweden, Switzerland, Brandenburg-Prussia, Denmark, Scotland, England, Protestant states of the Holy Roman Empire, the Cape Colony in Africa and North America. On 17 January 1686, Louis XIV claimed that out of a Huguenot population of 800,000 to 900,000, only 1,000 to 1,500 had remained in France.

The banner image is an early engraving of enslaved workers in Martinique.

England’s Charles II dies; an uprising ensues, is quelled

On the morning of February 2, 1685, England’s King Charles II had a sudden apoplectic fit. He died four days later, aged 54, Wikipedia tells us this:

On his deathbed Charles asked his brother, James, to look after his mistresses. He told his courtiers, “I am sorry, gentlemen, for being such a time a-dying”, and expressed regret at his treatment of his wife. On the last evening of his life he was received into the Catholic Church in the presence of Father John Huddleston, though the extent to which he was fully conscious or committed, and with whom the idea originated, is unclear. He was buried in Westminster Abbey “without any manner of pomp” on 14 February.

Not having any legitimate heirs, Charles was succeeded by his brother James, Duke of York, who had a long and profitable career as president of England’s sole (and monopolistic) slave-trading corporation, the Royal African Corporation.

James was also an ardent Catholic, a fact that had provoked a lot of opposition to his succession from the many equally ardent Protestants who were a strong force in the English Parliament.

James’s succession was also strongly opposed by his nephew, James, Duke of Monmouth, who was the oldest among the many children of Charles who were born out of wedlock– though Monmouth argued that his mother had in fact been married to Charles. Monmouth was a Protestant who had quite a wide popular following in England. In 1683, a plot to assassinate both Charles and his brother James had been uncovered– and Monmouth was implicated in it, though he was living in exile in the Dutch UP’s at the time.

James, the Duke of York, wanted to hurry to be crowned king, which happened on April 23. Almost immediately, he faced two armed uprisings. One was in Scotland, led by the Earl of Argyll, which was quelled– and Argyll captured– by June 18. The other was led by the36-year-old Duke of Monmouth. WP tells us that on June 11, he landed at Lyme Regis in southwest England with,

three small ships, four light field guns, and 1500 muskets. He landed… with 82 supporters, including Lord Grey of Warke, Nathaniel Wade, and Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun. They gathered about 300 men on the first day at Lyme Regis in Dorset, where a long statement prepared by Ferguson denounced the king… By 15 June he had a force in excess of 1,000 men.

But the new king had gotten wind of some aspects of the plot since before Monmouth left Holland, and after Monmouth landed in Lyme, the king and his local supporters pulled together an effective counter-operation. The decisive battle between the two sides was fought on July 6 at Sedgemoor. It was a strong victory for the king’s forces, who lost 27 killed and maybe 175 wounded, while Monmouth’s forces lost 1,300 killed or wounded and 2,700 captured.

Among those captured was Monmouth himself, who had fled the battlefield and reached the New Forest. The parliament that King James had convened had already pre-emptively declared Monmouth a traitor, so no further trial was required before he was sent to be executed at London’s Tower Hill.

At a specially convened series of trials held in the west country, Judge Jeffreys sentenced 320 of Monmouth’s supporters to death and “around 800” sentenced to be transported to the West Indies for ten years hard labor. WP adds these details about the political fall-out:

James II took advantage of the suppression of the rebellion to consolidate his power. He asked Parliament to repeal the Test Act and the Habeas Corpus Act, used his dispensing power to appoint Roman Catholics to senior posts, and raised the strength of the standing army. Parliament opposed many of these moves, and on 20 November 1685 James dismissed it.