In 1681 CE there were several notable developments in the continuing growth of West-European colonial networks worldwide. The grant that England’s King Charles II gave to William Penn to found (and own!) his own massive colony in mid-Atlantic North America was possibly not the most momentous. The English East India Company’s appointment of the self-made entrepreneur and economic theorist Josiah Child to be its new Director would definitely compete for that honor. But Child’s moment of greatest infamy would come later. So today I’ll focus mainly on Mr. Penn, whose ability to reconcile his Quaker faith with his support for the large-scale taking of other people’s land definitely bears scrutiny.

And in other world-empire news, in 1681 the Moroccan leader Moulay Ismail was able to chase the Spanish out of the Atlantic-coast enclave of Mehdya (aka Al-Ma’mura) that they’d held there for 67 years; the English governor of the Leeward Isles formally urged the genocide or ethnic cleansing of the Indigenes who remained on those islands; and King Charles, eager to dispel any hints that he might be a crypto-Catholic, organized a treason trial in which the chief Catholic archbishop in Ireland was hanged, drawn, and quartered.

So I’ll quickly review these other smaller items then return to William Penn.

Josiah Child appointed head of England’s EIC

Josiah Child had been born in around 1630 as the second son of a London merchant and grew up apprenticing to his father. When he was 25 he set up his own business as a “victualler” to the Navy at at time when it was growing a lot under Cromwell. He made lots of money at that and started writing about theories of mercantilist economics. His books Brief Observations concerning Trade and the Interest of Money and A New Discourse of Trade were both first published in 1668, making him one of England’s earliest theoretical economists. In a 1959 assessment of Child’s work the Anglo-American social scientist William Letwin judged that it was “of little theoretical importance” but added that he was “the most widely-read of seventeenth-century economic writers”.

Child became a significant stockholder in the EIC. In 1659 he was elected to one of the last “Commonwealth” parliaments, and then in 1673 he was elected again, this time to the staunchly Royalist “Cavalier Parliament”.

WP tells us that he became a loud advocate,

both by speech and by pen… of the East India Company’s claims to political power, as well as to its right of restricting competition to its trade, [and this] brought him to the notice of the shareholders. He was appointed a Director in 1677, rising to Deputy-Governor and finally became Governor of the East India Company in 1681. In this latter capacity, he directed the company’s policy as if it were his own private business.

Leeward Isles’ governor urges genocide

William Stapleton was an Anglo-Irish Royalist who had followed Charles II into exile in France. So of course when Charles’s monarchy was restored in 1660, he doled out large favors to his followers, and in Stapleton’s case this included “new opportunities in the West Indies”. WP tells us this:

In 1668, he was appointed Deputy Governor of Montserrat, and then in 1671 Governor of the Leeward Islands. In the same year, he married Anne Russell, the daughter of Colonel Randolph Russell, of Nevis, bringing him into a network of locally established planter families. He acquired the Waterwork plantation on Montserrat… In 1678, on behalf of the Crown, he granted the Figtree plantation on Nevis to Charles Pim and speedily bought that from him for 400,000 pounds of muscovado sugar. In 1679, he granted the Carleton plantations on Antigua to his older brother, Redmond Stapleton, then in 1682 bought them from his brother for 100,000 pounds of muscovado sugar. He died in Paris in 1686, leaving complicated financial affairs behind him.

No kidding! If those little examples of thinly-veiled self-dealing are any indication, there may well have been a lot more financial shenanigans to sort out, too…

But anyway, along the way, in August 1681, he wrote to the Lords of Trade and Plantations in London, reporting on an attack that a group of “Indians” in Barbuda, a small island just north of Antigua, had launched on some English settlers there. He added this (Aug. 16, #204):

I beg your pardon if I am tedious, but I beg you to represent to the King the necessity for destroying these Carib Indians, and move him either to order the Governor of Barbados to do it, which is an easy thing for that Government to do through its nearness to St. Vincent and Dominica, or to put me in capacity to perform that good piece of service whilst we are in amity with the French. I beg at least that it may not be disliked if I take all opportunities to drive them to the Main if I cannot compass their total destruction. I need not dwell on the importance of this affair to the safety of the Leeward Islands, not doubting that you are sensible thereof. We are now as much on our guard as if we had a Christian enemy, and more, for we fear no such at this time of year, neither can any such surprise us but these cannibals who never come Marte aperto, though they have generally good fire-arms from the French and Dutch, and are as good firemen as any.

I give a hat-tip here to Sir Hilary Beckles’s work Britain’s Black Debt, which referenced this incident on p.25. But I wish he had had someone check the footnotes better as this is one of a number of cases I have noted in which there’s a small but significant typo in the citation. Sigh.

Moroccans force Spanish out of Mehdya

The Portuguese had been there first, of course. But the Spanish got there and took it in 1614. Then, in 1681, this:

it was conquered by the Alaouite ruler Moulay Ismaïl. According to tradition, the Bishop of Cadiz had commissioned a statue of Jesus Christ for the church at La Mamora [Mahdya], which was in his diocese. When the Moroccans reoccupied the town in 1681 they took the statue as loot, and later received a ransom from the Spanish for the return of the statue, which was taken to Madrid where it is nowadays venerated under the name of Cristo de Medinaceli.

(The banner image above is a near-contemporary Spanish painting of the Moroccan liberators dragging the statue in the street.)

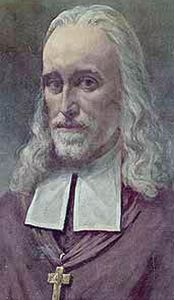

Catholic Archbishop Plunkett convicted & gruesomely executed

By 1681, the allegations that King Charles was a crypto-Catholic were swirling around England very intensely. Three times between January 1679 and March 1681, England had held a parliamentary election; the Parliament had sought to pass an Exclusion Act that would forbid the childless king’s recognizedly Catholic brother James, Duke of York, from succeeding him onto the throne; and Charles had thereupon dismissed the Parliament.

In those circumstances, it was little surprise that there were all kinds of allegations of “Popish plots” swirling around the country, and one of those ensnared Oliver Plunkett, the Catholic Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland.

In June 1681, Plunkett was arrested, charged, and,

found guilty of high treason… “for promoting the Roman faith”, and was condemned to death. In passing judgement, the Chief Justice said: “You have done as much as you could to dishonour God in this case; for the bottom of your treason was your setting up your false religion, than which there is not any thing more displeasing to God, or more pernicious to mankind in the world”.

And on July 1, 1681, Plunkett was hanged, drawn, and quartered per the English standards of that day for punishing traitors.

In 1975 he was canonized as a saint.

William Penn and his Sylvania

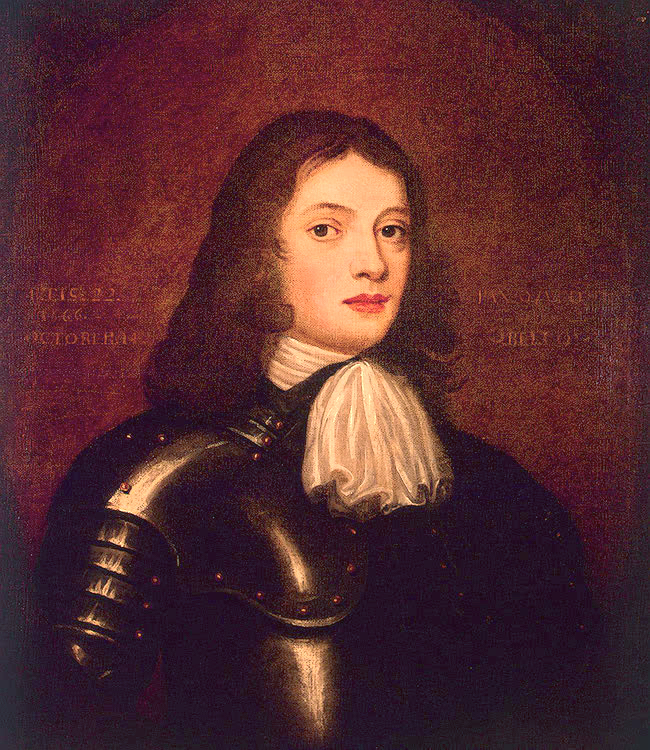

William Penn (Jr.) was born in 1644. His dad, also William Penn, had been a sea-commander who in the First English Civil War (1642-46) had fought on the side of Parliament but was sometimes under suspicion for his frequent contacts with the Royalists. The dad had fought against Royalist forces in Ireland, for which service Cromwell gave him some lands there. He had also been a commander of the naval force Cromwell sent to the Caribbean in 1654 in pursuit of his “Western Design” against Spain’s forces there. When he came under political attack for the failures in the “Western design”, he went into semi-exile in his lands in Ireland, and it was there that young William first came into contact with, and was increasingly persuaded by, a local Quaker.

In 1660, the monarchy was restored– and Adm. Penn had had a part in that. The WP page on young William tells us that that year he,

arrived at Oxford and enrolled as a gentleman scholar with an assigned servant. The student body was a volatile mix of swashbuckling Cavaliers (aristocratic Anglicans), sober Puritans, and nonconforming Quakers. The new government’s discouragement of religious dissent gave the Cavaliers the license to harass the minority groups. Because of his father’s high position and social status, young Penn was firmly a Cavalier but his sympathies lay with the persecuted Quakers. To avoid conflict, he withdrew from the fray and became a reclusive scholar.

He would later reflect that, “I had no relations that inclined to so solitary and spiritual way; I was a child alone. A child was given to musing, occasionally feeling the divine presence.” Then this:

Penn returned home [to London] for the extraordinary splendor of the King’s restoration ceremony and was a guest of honor alongside his father, who received a highly unusual royal salute for his services to the Crown.

So his life in his early years was pretty mixed-up. He went to Paris to study some. In 1666 he,

was sent to Ireland… to manage the family landholdings. While there he became a soldier and took part in suppressing a local Irish rebellion. Swelling with pride, he had his portrait painted wearing a suit of armor, his most authentic likeness. His first experience of warfare gave him the sudden idea of pursuing a military career, but the fever of battle soon wore off after his father discouraged him…

That year, of course, was the Great Fire of London– so richly described by the Penn family’s neighbor the diarist Samuel Pepys (who also quite possibly had affairs with both young William’s mother and his sister.) Anyway, post-fire London didn’t suit him so he returned to Cork and began to hang out with the Quakers again.

Then this:

Soon Penn was arrested for attending Quaker meetings. Rather than state that he was not a Quaker and thereby dodge any charges, he publicly declared himself a member and finally joined the Quakers at the age of 22. In pleading his case, Penn stated that since the Quakers had no political agenda (unlike the Puritans) they should not be subject to laws that restricted political action by minority religions and other groups. Sprung from jail because of his family’s rank rather than his argument, Penn was immediately recalled to London by his father.

His dad was outraged and kicked him out of the family home, so he began couch-surfing in the homes of other Quakers and became a close friend of the sect’s founder, George Fox. WP tells us this:

Penn traveled frequently with Fox, through Europe and England. He also wrote a comprehensive, detailed explanation of Quakerism along with a testimony to the character of George Fox, in his introduction to the autobiographical Journal of George Fox. In effect, Penn became the first theologian, theorist, and legal defender of Quakerism, providing its written doctrine and helping to establish its public standing.

He started publishing his own religious tracts that excoriated all the religious currents then active in England except the Quakers. In 1668 was imprisoned in the Tower of London for publishing the second of these. There, he was “placed in solitary confinement in an unheated cell and threatened with a life sentence, … accused of denying the Trinity”– a charge that he refuted.

But he got treated a lot better than Oliver Plunkett would be, in 1681. In 1668, Penn was given writing materials while he was in prison. I guess the authorities hoped he would write a retraction? He did not but produced another Quaker tract instead. He then,

petitioned for an audience with the King, which was denied but which led to negotiations on his behalf by one of the royal chaplains. Penn bravely declared, “My prison shall be my grave before I will budge a jot: for I owe my conscience to no mortal man.” He was released after eight months of imprisonment.

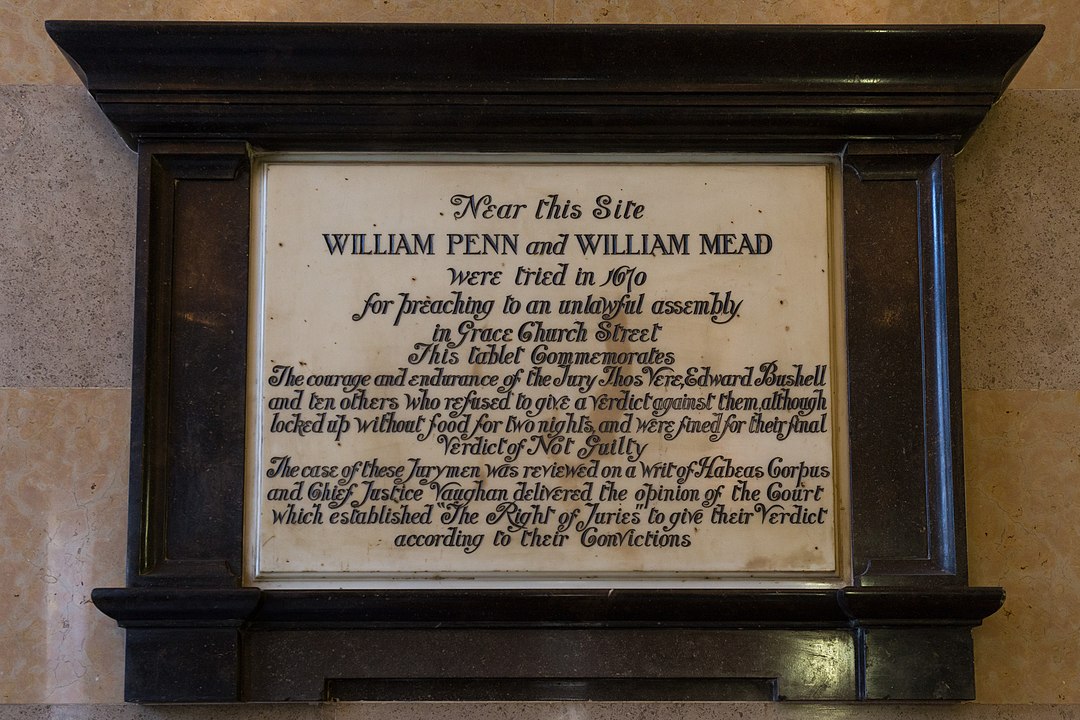

He then went back to his mission-izing on behalf of the Quakers and had further run-ins with the law (in one of which the judge even ended up sending the jury back into the prison with him because it had refused to convict him.)

Then this:

With his father dying, Penn wanted to see him one more time and patch up their differences. But he urged his father not to pay his fine and free him, “I entreat thee not to purchase my liberty.” But the Admiral refused to let the opportunity pass and he paid the fine, releasing his son.

The old man had gained respect for his son’s integrity and courage and told him, “Let nothing in this world tempt you to wrong your conscience.” The Admiral also knew that after his death young Penn would become more vulnerable in his pursuit of justice. In an act which not only secured his son’s protection but also set the conditions for the founding of Pennsylvania, the Admiral wrote to the Duke of York, the heir to the throne.

The Duke and the King, in return for the Admiral’s lifetime of service to the Crown, promised to protect young Penn and make him a royal counselor

In the late 1670s, persecution of the Quakers was increasing and he proposed an ingenious solution to the royals:

Seeing conditions deteriorating, Penn decided to appeal directly to the King and the Duke. Penn proposed a solution which would solve the dilemma—a mass emigration of English Quakers. Some Quakers had already moved to North America, but the New England Puritans, especially, were as hostile towards Quakers as Anglicans in England were, and some of the Quakers had been banished to the Caribbean. In 1677 a group of prominent Quakers that included Penn purchased the colonial province of West Jersey (half of the current state of New Jersey). That same year, two hundred settlers from the towns of Chorleywood and Rickmansworth in Hertfordshire and other towns in nearby Buckinghamshire arrived, and founded the town of Burlington [New Jersey]. George Fox himself had made a journey to America to verify the potential of further expansion of the early Quaker settlements…

With the New Jersey foothold in place, Penn pressed his case to extend the Quaker region. Whether from personal sympathy or political expediency, to Penn’s surprise, the King granted an extraordinarily generous charter which made Penn the world’s largest private (non-royal) landowner, with over 45,000 square miles (120,000 km2). Penn became the sole proprietor of a huge tract of land west of New Jersey and north of Maryland (which belonged to Lord Baltimore), and gained sovereign rule of the territory with all rights and privileges (except the power to declare war). The land of Pennsylvania had belonged to the Duke of York, who acquiesced, but he retained New York and the area around New Castle and the Eastern portion of the Delmarva Peninsula. In return, one-fifth of all gold and silver mined in the province (which had virtually none) was to be remitted to the King, and the Crown was freed of a debt to the Admiral of £16,000, equal to roughly £2,526,337 in 2008.

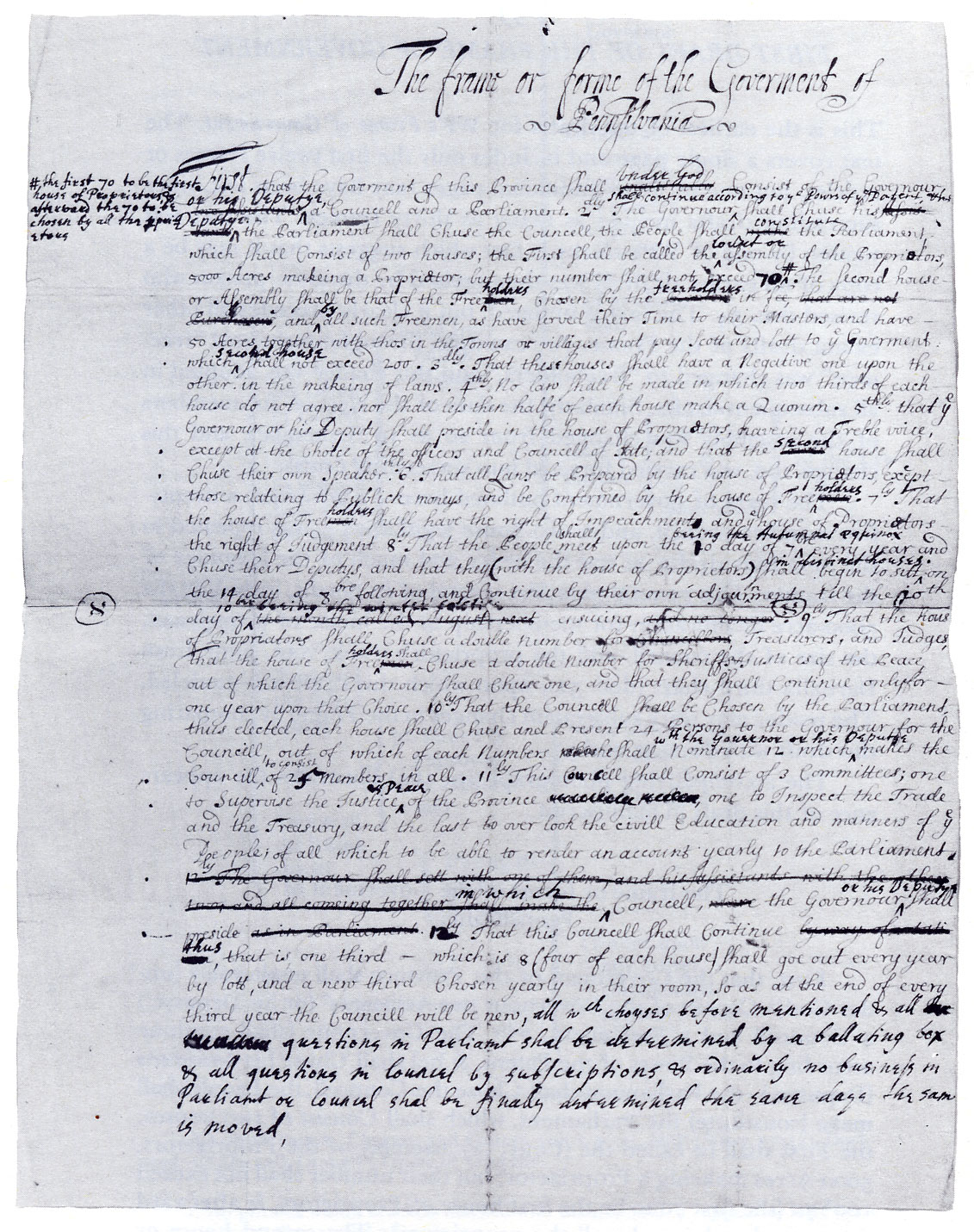

Penn first called the area “New Wales”, then “Sylvania” (Latin for “forests” or “woods”), which King Charles II changed to “Pennsylvania” in honor of the elder Penn. On 4 March 1681, the King signed the charter and the following day Penn jubilantly wrote, “It is a clear and just thing, and my God who has given it to me through many difficulties, will, I believe, bless and make it the seed of a nation.” Penn then traveled to America and while there, he negotiated Pennsylvania’s first land-purchase survey with the Lenape Indian tribe. Penn purchased the first tract of land under a white oak tree at Graystones on 15 July 1682. Penn drafted a charter of liberties for the settlement creating a political utopia guaranteeing free and fair trial by jury, freedom of religion, freedom from unjust imprisonment and free elections.

Besides achieving his religious goals, Penn had hoped that Pennsylvania would be a profitable venture for himself and his family. But he proclaimed that he would not exploit either the natives or the immigrants, “I would not abuse His love, nor act unworthy of His providence, and so defile what came to me clean.” To that end, Penn’s land purchase from the Lenape included the latter party’s retained right to traverse the sold lands for purposes of hunting, fishing, and gathering. Though thoroughly oppressed [?], getting Quakers to leave England and make the dangerous journey to the New World was his first commercial challenge. Some Quaker families had already arrived in Maryland and New Jersey but the numbers were small. To attract settlers in large numbers, he wrote a glowing prospectus, considered honest and well-researched for the time, promising religious freedom as well as material advantage, which he marketed throughout Europe in various languages. Within six months he had parcelled out 300,000 acres (1,200 km2) to over 250 prospective settlers, mostly rich London Quakers. Eventually he attracted other persecuted minorities including Huguenots, Mennonites, Amish, Catholics, Lutherans, and Jews from England, France, Holland, Germany, Sweden, Finland, Ireland, and Wales.

Lots of Penn’s ambitions for building a just, peaceable society would later be over-run by land-grabbing and greed, including by his sons.