1675 CE feels like an emotional year for me to write about. As an English-origined settler living in North America I totally realize that I am here because of White privilege and as a beneficiary/participant in the continuing story of “White”, English land-grabbing, exploitation, and dispossession of these lands. I live in the traditional lands of the Nacotchtanks and Piscataways. Other than acknowledge this, what can I do about this? One thing I can do is try to learn and understand the story of English empire-building here and worldwide and to tell it in a way that might help other people understand it in new ways, as well.

Frequently, though, I feel waves of sadness when I think about all the extremely brutal things that were done to install “White” (and specifically “White” English) privilege here on these lands and on so many other lands worldwide. But along with the sadness is a sense of awe at the steadfastness and resilience of all those oppressed people who worked and organized to try to resist it along the way. It is so important to tell their stories, too. Let us absolutely not forget them.

So today, I’ll be writing about three notable developments in 1675 in the ongoing conflicts in the Americas between English colonists and the Indigenes and enslaved Africans whom they were violently oppressing there:

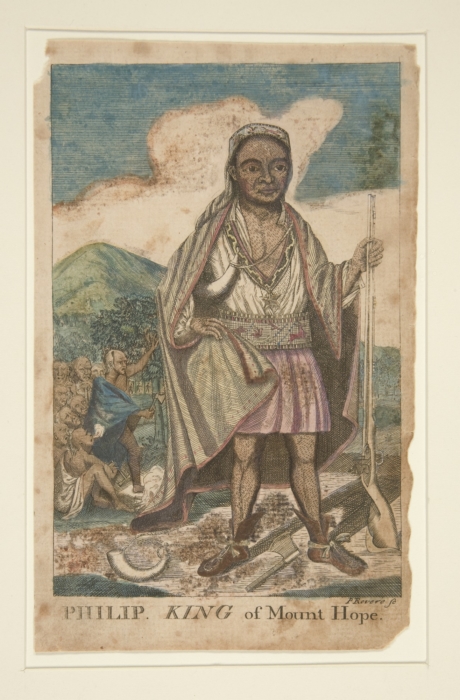

- In the mainly-Puritan “New England” colonies on the North American mainland, the sachem of the Wampanoag people, Metacomet, known by the colonists as “King Philip” started an uprising against the colonists.

- In the Leeward Islands, Governor William Stapleton sent a force into Dominica in pursuit of his plan to destroy “all the Carib Indians”.

- In Barbados, enslaved African workers planned an uprising to install one of their number, Cuffy, as king of the island.

The uprising of Metacomet (aka ‘King Philip’)

This was a serious intifada of native peoples in New England against the English colonists who’d been encroaching on their traditional lands for 50 years or more by now. In traditional American history today it is called “King Philip’s War”. Let’s rename it.

By 1675, the population of English-origined colonists in “New England” had reached about 65,000, and that of the various Native peoples, combined, had been reduced to around 10,000, mainly through the spread of disease. This page on English-WP tells us this about these populations:

New England colonists… lived in 110 towns, of which 64 were in the Massachusetts Bay colony, which then included the southwestern portion of Maine. The towns had about 16,000 men of military age who were almost all part of the militia, as universal training was prevalent in all colonial New England towns… Joint forces of militia volunteers and volunteer Native allies were found to be the most effective. The Native allies of the colonists numbered about 1,000 from the Mohegans and Praying Natives, with about 200 warriors.

By 1676, the regional Native population had decreased to about 10,000 (exact numbers are unavailable), largely because of epidemics. These included about 4,000 Narragansetts of western Rhode Island and eastern Connecticut, 2,400 Nipmucs of central and western Massachusetts, and 2,400 combined in the Massachusett and Pawtucket tribes living around Massachusetts Bay and extending northwest to Maine. The Wampanoags and Pokanokets of Plymouth and eastern Rhode Island are thought to have numbered fewer than 1,000. About one in four were considered to be warriors. By then, the Natives had almost universally adopted steel knives, tomahawks, and flintlock muskets as their weapons. The various tribes had no common government. They had distinct cultures and often warred among themselves, although they all spoke related languages from the Algonquian family.

In January, a “Praying Native” called John Sassamon was found dead in an icy pond in southeastern Massachusetts. He had been an early graduate of Harvard College (!) and was a cultural mediator who served as a line of communication between the Wampanoag sachem Metacomet and the English. In early 1675 or perhaps late 1674, he had reported to the governor of Plymouth Colony that Metacomet was planning Native attacks on colonial settlements. Metacomet was hauled before a colonial court, but since officials said they had no evidence they let him off with a warning.

I think that was before Sassamon’s body was discovered. When it was, Plymouth Colony officials arrested three Wampanoags, including an advisor to Metacomet. WP tells us that “A jury that included six Native elders convicted the men of Sassamon’s murder, and they were executed by hanging on June 8, 1675, at Plymouth.”

(Why does this story of story of interpreters, their– possibly fallacious or self-serving– reports against Indigenes, and harsh colonial punishments against Indigenes that are cloaked in some quasi-“legitimacy” of having Indigenous buy-in seem so very modern and ongoing?)

So after the hangings of the three Wampanoags, Metacomet’s Uprising started. And it quickly spread. It’s worth trying to read the whole account of it on English-WP. For now, here’s just part of their summary:

Native raiding parties attacked homesteads and villages throughout Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Maine over the next six months, and the Colonial militia retaliated. The Narragansetts remained neutral, but several individual Narragansetts participated in raids of colonial strongholds and militia, so colonial leaders deemed them to be in violation of peace treaties. The colonies assembled the largest army that New England had yet mustered, consisting of 1,000 militia and 150 Native allies, and Governor Josiah Winslow marshaled them to attack the Narragansetts in November 1675. They attacked and burned Native villages throughout Rhode Island territory, culminating with the attack on the Narragansetts’ main fort in the Great Swamp Fight. An estimated 600 Narragansetts were killed, and the Native coalition was then taken over by Narragansett sachem Canonchet. They pushed back the colonial frontier in Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Rhode Island colonies, burning towns as they went, including Providence in March 1676. However, the colonial militia overwhelmed the Native coalition and, by the end of the war, the Wampanoags and their Narragansett allies were almost completely destroyed. On August 12, 1676, Metacom fled to Mount Hope where he was killed by the militia.

You have to go to Metacomet’s own page on WP to find out what happened to him then:

Hunted by a group of rangers led by Captain Benjamin Church, King Philip was fatally shot by a praying Indian named John Alderman, on August 12, 1676, in the Miery Swamp near Mount Hope in Bristol, Rhode Island. After his death, his wife and nine-year-old son were captured and sold as slaves in Bermuda. Philip’s head was mounted on a pike at the entrance to Plymouth, Massachusetts, where it remained for more than two decades. His body was cut into quarters and hung in trees. Alderman was given Philip’s right hand as a trophy.

The main page on Metacomet’s Uprising says this: “The war was the greatest calamity in seventeenth-century New England and is considered by many to be the deadliest war in Colonial American history.” I’m not sure about that. Deadly for which side, I wonder? Anyway, Metacomet’s Uprising of 1675 belongs in the annals of the courageous efforts of North American Indigenes to resist the ongoing land-grabbing, violence, and oppression of the English colonists, alongside the Powhatan uprising against “Jamestown” in 1622.

The Wikipedia page on the uprising estimates that as a result of the uprising the English side suffered “c.2,500” casualties and losses, and the Native side “c.3,000”. It also says this:

In the space of little more than a year, 12 of the region’s [settler] towns were destroyed and many more were damaged, the economy of Plymouth and Rhode Island Colonies was all but ruined and their population was decimated, losing one-tenth of all men available for military service. More than half of New England’s towns were attacked by Natives. Hundreds of Wampanoags and their allies were publicly executed or enslaved, and the Wampanoags were left effectively landless.

It adds this possibly significant comment, that the uprising:

began the development of an independent American identity. The New England colonists faced their enemies without support from any European government or military, and this began to give them a group identity separate and distinct from Britain.

By the way, the banner image above is a fairly old engraving of a Native American attack on a settlers’ garrison during Metacomet’s Uprising.

Stapleton and Atkins’s war of extermination against Caribs/Kalinagos in Dominica

By the 1670s, it was clear that establishing and running sugar plantations on Caribbean islands could be an extremely profitable business for English investors, who were now very experienced at integrating those plantations into their outrageously barbaric “triangular trade”, one key leg of which involved shipping enslaved Africans from their home continent over to work as enslaved labor in the fields and cane-mills of the plantations. However, in 1675 the native Kalinagos or Carib people still controlled many of their own islands in the Caribbean, especially in the Lesser Antilles, and were able to resist attempts by the English, Spanish, or other European colony-builders to take their lands.

The great West Indian historian Sir Hilary Beckles writes in his book Britain’s Black Debt that, “The success of the Kalinagos in holding on to a significant portion of the Windwards, and their weakening of English settlements in the Leewards, fuelled the determination of the English state to destroy all of them.” (pp.28-29.)

He also noted an interesting shift in the dynamic between the Kalinagos and those of the enslaved Africans who’d been able to escape their enslavers on the islands– known as Maroons:

(The “Labat” he cites, is I think, this French Dominican monk who visited the Caribbean a little later.) Anyway, here’s how Beckles’s narration continues:

Well, so much for St. Vincent. Now, on to Stapleton and Dominica.

William Stapleton had been the governor of the (British) Leeward Islands since those colonies were grouped together as a single administrative unit in 1671. In early February 1675, he wrote to the Council for Plantations as follows (#428):

The Indians of Dominica have again committed murders and rapines upon Antigua a little before Christmas last, whereupon we empowered the Deputy Governor, Col. Philip Warner, with 6 small companies of foot, to go to Dominica to be revenged on those heathens for their bloody and perfidious villanies, who killed 80, took some prisoners, destroyed their provisions, and carried away most of their periagoes and canoes, as their warlike vessels are called; his pretended brother, Indian Warner (reputed natural son to Sir Thomas), fell amongst his fellow heathens, who, though he had an English commission, was a great villain, and took a French commission, which makes him suspect that these Indians have been put on by those who made use of them in the late war.

Beseeches their Lordships to move his Majesty that they may have some frigates as their neighbours have constantly relieved, and if he does not destroy those heathens who have so often treacherously spilled English blood, or at least render them incapable of assisting their neighbours in time of war, let him be severely punished. Must confess this design may be better effected by the Government of Barbadoes, which is nearer and to windward, and no better service could be performed for these inhabitants, who are forced to watch continually for a heathen enemy, than their absolute destruction,—a thing easily to be effected,—or at least to reduce them to live on the main land.

In mid-February 1675, Jonathan Atkins, the Governor of Barbado(e)s filed his own report to the Council for Plantation (#439). (Note that these reports are recorded in the “Calendars” in the State Papers collection in London using a third person locution where the original might have been in the first person.) In his report, Atkins wrote about a complicated sequence of events including a massacre that had apparently been committed by English soldiers the previous December. Atkins included with his report a deposition from William Hamlyn, who had commanded a sloop that carried that carried Col. Philip Warner, the Deputy Governor of Antigua, and two other ships, “carrying in the whole 300 men,” who arrived in Dominica on Christmas Day (1674).

Hamlyn continued: “Said vessels were met by Thomas Warner, Deputy Governor for his Majesty”– or, as Atkins had described Thomas Warner, “having a commission from Barbadoes as Lieutenant-Governor for the King, and being the only person in these parts that asserted the English interest and suffered imprisonment and irons during the war for his service to the King.” Thomas Warner was also Philip Warner’s half-brother, being the son of Philip’s English planter father by a Kalinago wife, and therefore half-Kalinago himself.

In Hamlyn’s deposition he described himself as

understanding Col. Warner’s design was the 300 men should fall upon the Windward Indians [in Dominica] for some injuries supposed to be done by them to him [Col. Warner] on Antigua, agreed to assist him with 30 Indians, and ordered 30 more to attend them to carry orders. Four Windward Indians were slain, and believes 30 at least were killed, besides three that were drawn by a flag of truce to come on board and there killed. After the dispute was over, Col. Warner invited Thomas Warner and his Indians, to the number of 60 or 70 men, women, and children, to an entertainment of thanks, and having made them very drunk with rum, gave a signal, and some of the English fell upon and destroyed them. Afterwards an Indian calling himself Thomas Warner’s son came on board Col. Warner’s ship, and told him he had killed his father and all his friends, and prayed him to cause him also to be killed, holding his head of one side to receive a blow, which by Col. Philip’s order was given him, and he was thrown overboard. Deponent took an Indian boy in his arms to preserve him, but the child was wounded in his arms and afterwards killed; believes this slaughter was by the sole direction of Col. Warner, against the consent of his officers, several of whom he heard declare against it. In pursuit of the Windward Indians, two or three English were killed in fight. Said Thos. Warner being advertized [= having previously been warned?] that Col. Warner designed to kill him, replied he was better assured of his kindness and fidelity, being his half brother. Deponent heard Col. Warner order Cornet Saml. Winthorpe to kill Thos. Warner, who refused to do so. Col. Warner and his men being in great distress for provisions, were provided by Thos. Warner and his Indians with what they could.

The way these reports were recorded in London make is hard for us coming 350 years later to try to understand them. (And who knows what personal scores the people filing the reports were trying to settle, anyway?) But still, there is enough in these records to give a glimpse into what the English were doing in the distant Rum Islands there in the Caribbean.

Beckles also tells us (p.33) that,

In spite of losses sustained in Dominica, the Kalinagos continued to use the island as a military base for self-defense. In July 1681, three hundred Kalinagos from St. Vincent and Dominica, in six canoes… attacked the English settlements in Barbuda. The English were caught by surprise. Eight of them were killed and their houses destroyed. The action was described [by Stapleton] as swift and without warning.

A planned uprising of the enslaved in Barbados

1675 was a busy year for Barbados’s Governor Atkins. In her book Christian Slavery, Katharine Gerbner tells us (pp.66-67) that in May of that year, a planter called Gyles Hall was informed by one of the enslaved women working for him that another of his enslaved workers, “a young man of about eighteen from the Gold Coast” had been involved in a plot for a broad uprising against the planters– but had stepped back from joining it. The plot, according to an account of the affair written in 1676 (presumably by an English settler), had been aimed at taking over the island and crowning “an ancient Gold-coast Negro” named Cuffy as king of the island.

The enslaved woman, alternately named by contemporary English sources as either Anna or Fortuna– though who knows what her real, original name was?– informed either Gyles Hall or a member of his family. Then, this happened (Gerbner, p.66):