Lots of shortish news this year, 1650 CE. Throughout the year, the politically and religiously complex Commonwealth vs. monarchist conflict continued to roil England, Scotland, and Ireland (though mainly the latter two of those lands.) I shall note below only what was happening in Scotland and a small event in England. Remember though that these were just two parts of the broader picture.

I guess I will start with the news about Harvard since I find it amusing and little bit informative. English-WP tells us that:

In 1650, at the request of Harvard President Henry Dunster, the Great and General Court of Massachusetts issued the body’s charter, making it now the oldest corporation in the Americas. The subsequent Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts confirmed that, despite the change in government due to the American Revolution, the corporation would continue to “have, hold, use, exercise and enjoy” its property and legal privileges.

Given the role of knowledge production and dissemination in supporting the growth and development of both imperialism and the capital structures that flowed from it, I think Harvard’s “pioneering” role as a corporation seems appropriate.

On to the year’s other news. I’ll take it in this order:

- Charles (II) in Scotland

- Quakers in England

- Political change in Amsterdam

- English imperialism in India and Anguilla.

Charles (II) in Scotland

On June 23 Charles, the 20-year-old eldest son of the recently beheaded King Charles I, arrived in Scotland after travelling by sea from The Hague. Scotland’s powerful Covenanter movement had agreed they would recognize him as their country’s King Charles II provided he accede to their demand for the abolition of bishops in the churches of both Scotland and England. He had agreed to do so– but he never really got along with the Covenanters. After he arrived in Scotland, Cromwell interrupted his brutal anti-nationalist campaigning in Ireland and came to Scotland to confront him.

This happened:

On 3 September 1650, the Covenanters were defeated at the Battle of Dunbar [east of Edinburgh] by a much smaller force led by Oliver Cromwell. The Scots forces were divided into royalist Engagers and Presbyterian Covenanters, who even fought each other. Disillusioned by the Covenanters, in October Charles attempted to escape from them and rode north to join with an Engager force, an event which became known as “the Start”, but within two days the Presbyterians had caught up with and recovered him. Nevertheless, the Scots remained Charles’s best hope of restoration, and he was crowned King of Scotland at Scone Abbey on 1 January 1651.

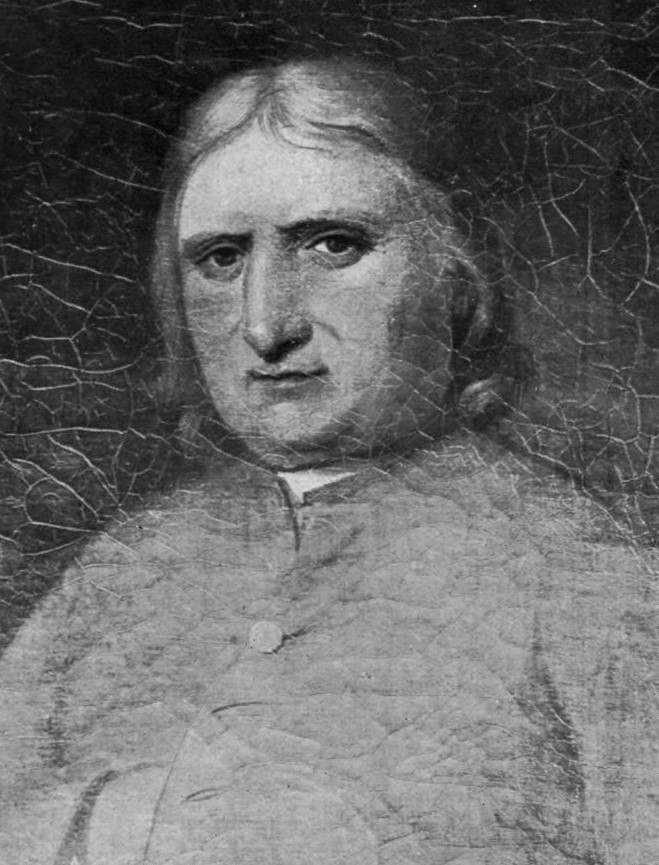

The banner image above is a painting of Cromwell at Dunbar.

Quakers in England

So, among all the many politico-religious sects and movements that had grown up in the preceding years of turmoil in England, one was a deeply anti-clerical movement led by a charismatic preacher called George Fox. Fox’s followers called themselves “Children of the Light” or “Friends of the Truth”, and later simply “Friends”. The 1650s were one of their most creative periods. But they refused to take part in the practice (still broadly required today in many countries) of swearing public oaths of truthfulness in courts and so on with their hands on a Bible, saying that their words should be themselves be considered truthful, without oath-swearing. Their refusal to do this, along with other infractions like refusing to serve in the New Model Army, got Fox and his followers into a lot of trouble under Cromwell.

Fox himself was imprisoned a number of times, often for lengthy periods and in horrible circumstances. In one of his trials, WP tells us this happened:

At Derby in 1650 he was imprisoned for blasphemy; a judge mocked Fox’s exhortation to “tremble at the word of the Lord”, calling him and his followers “Quakers”. After he refused to fight against the return of the monarchy (or to take up arms for any reason), his sentence was doubled.

Originally, then, the name “Quakers” was meant as a taunt. But it stuck. And so did the Quakers themselves. It is the only one of those many populist religio-political movements that arose in the 1640s that is still around today. (Full disclosure: I grew up Anglican and became a Quaker by convincement over 20 years ago.)

Political change in Amsterdam

I confess I’ve been confused about the 17th-century political leadership situation in the Netherlands United Provinces for too long. One of my questions was, “What was a Stadtholder?” In 1650 something happened that made it seem more important to figure out…

So, there were seven provinces in the federation and each had a Stadtholder. Here’s the definition from WP:

In the Low Countries, stadtholder was an office of steward, designated a medieval official and then a national leader. The stadtholder was the replacement of the duke or earl of a province during the Burgundian and Habsburg period (1384 – 1581/1795). The title was used for the official tasked with maintaining peace and provincial order in the early Dutch Republic and, at times, became de facto head of state of the Dutch Republic during the 16th to 18th centuries, which was an effectively hereditary role.

Until November 6, 1650– and also, I think, for several decades before then– Holland, Zeeland, and three of the other UPs all had the same Stadtholder, William II, also known as the Prince of Orange. And since Holland was easily the largest of the seven UPs, this Stadholder was the person with most “head of state”-type authority in the whole country. His wife, Princess Mary, was Charles II of England’s slightly younger sister. (This fact will become important later.) On November 6, William died aged 24, without children. His first child also William, was born a week after his death.

Now if that had been the Topkapi Palace or wherever, I imagine they could have fudged the child’s birth date and a powerful mother-in-law would have stepped in as the babe’s regent. Instead, Holland, Zeeland, and the other three UPs entered what Dutch historiography calls the First Stadtholderless Period. This WP page notes the following:

The First Stadtholderless Period… happened to coincide with the zenith of the Golden Age of the Republic. The term has acquired a negative connotation in 19th-century Orangist Dutch historiography, but whether such a negative view is justified is debatable. Republicans argue that the Dutch state functioned very well under the regime of Grand Pensionary Johan de Witt, despite the fact that it was forced to fight two major wars with England, and several minor wars with other European powers.

A “grand pensionary” is similar to a modern-day prime minister, or perhaps even more so an Ottoman Grand Vizier. It is notable that the UPs managed just fine without Holland, Zeeland, etc having a Stadtholder!

WP gives more details about the UPs’ achievements in the First Stadtholderless Period:

Thanks to friendly relations with France, a cessation of hostilities with Spain, and the relative weakness of other European great powers, the Republic for a while was able to play a pivotal role in the “European Concert” of nations, even imposing a pax nederlandica in the Scandinavian area. A convenient war with Portugal enabled the Dutch East India Company to take over the remnants of the Portuguese empire in Ceylon and south India. After the end of the war with Spain in 1648, and the attendant end of the Spanish embargo on trade with the Republic that had favored the English, Dutch commerce swept everything before it, in the Iberian Peninsula, the Mediterranean Sea and the Levant, as well as in the Baltic region. Dutch industry, especially textiles, was as yet not hindered by protectionism. As a consequence, the Republic’s economy enjoyed its last great economic boom.

Politically, the Staatsgezinde (Republican) faction of the ruling Dutch Regents such as Cornelis de Graeff and Andries Bicker reigned supreme. They even developed an ideological justification of republicanism (the “True Freedom”) that went against the contemporary European trend of monarchical absolutism, but prefigured the “modern” political ideas that led to the American and French constitutions of the 18th century. There was a “monarchical” opposing undertow, however, from adherents of the House of Orange who wanted to restore the young Prince of Orange to the position of Stadtholder that his father, grandfather, great-uncle, and great-grandfather had held. The republicans attempted to rule this out by constitutional prohibitions, like the Act of Seclusion. But they were unsuccessful, and the Rampjaar (“Year of Disaster”) of 1672 brought about the fall of the De Witt regime and the return to power of the House of Orange.

(But 1672 is still far ahead.)

English imperialism in India and Anguilla

And what, you may ask, has been happening to the English Empire meanwhile? Here’s a snippet of information from the tiny (35 sq. miles) Antilles island of Anguilla: “Traditional accounts state that Anguilla was first colonised by English settlers from Saint Kitts beginning in 1650. The settlers focused on planting tobacco, and to a lesser extent cotton.”

The East India Company (EIC) was, of course, a much larger organization than the various little planters’ companies that were slowly spreading the English practice of using the coerced labor of enslaved Africans to produce hyper-profits from their plantations in the West Indies. News of the political turmoil at home in England clearly took some time to travel around the Cape of Good Hope and reach the EIC’s local HQ in Surat, or other places in India, but I suppose the news of Charles I’s January 1649 beheading must have arrived there had arrived there later that year or in 1650? Of greater impact for the EIC’s people in Surat were the continuing difficulties their bosses back in London were having, amidst the political unrest, in raising the additional rounds of capital that Surat so desperately needed.

But do you remember Hooghly, the river system and eponymous city over in Bengal where the Mughals a few years ago briefly kicked out the Portuguese and their missionaries as a way of showing them who was boss? The early-20th century English historian William Wilson Hunter (WWH) tells us that this was what the EIC was able to achieve there in 1650 (pp.244-46):

The arrival of the English at Hugli in 1650 promised an accession of trade to the new imperial port, and an increased customs-revenue to the Moghul governor. They came as four peaceable merchants who had left their ship the Lyoness far off in the Balasor roadstead, and only asked leave to sell the goods brought up the river in small native boats. The letter of instructions drawn up for their guidance mingled religious admonition with shrewd commercial advice. “Principally and above all things,” runs its opening paragraph, “you are to endeavour with the best of your might and power the advancement of the glory of God, which you will best do by walking holily, righteously, prudently, and Christianly in this present world,” that so, you may enjoy the quiet and peace of a good conscience toward God and man.” In the next place they were to buy in the cheapest markets a cargo of Bengal sugars, silks, and “Peter” (saltpetre); to “enquire secretly” into the business methods of the Dutch; and above all to procure a license for trade which “may outstrip the Dutch in point of privilege and freedom.” They carried with them an able Hindu, Narayan (or “Narrand”) by name, who had been the “Company’s broker” since our first settlement in Orissa in 1632, and who now repaid its confidence in the face of intrigues against him, by rendering good service to us in Bengal.

They also found a friend at the viceregal court then held at Raj Mahal, one of the shifting Ganges capitals, above the point where the mighty river splits up into its network of deltaic channels. Gabriel Boughton, doctor of the Company’s ship Hopewell, had in 1645 been lent to a nobleman in the Imperial service, and was in 1650 Chirurgeon to the Moghul Viceroy of Bengal, Shah Shuja, who was a son of the reigning emperor, Shah Jahan. In or about the latter year Boughton obtained from his patron a license for free trade by the English in Bengal in return for three thousand rupees judiciously expended at the viceregal court. But as the document was lost three years later, by Mr. Waldegrave on a land journey to Madras, it remains doubtful whether the license confined our trade to the seaports or sanctioned it also in the interior. The Masulipatam factory rewarded Mr. Boughton with a gift “of gay apparel” – a dress of honour suitable to a high personage in attendance on the Viceregal Court – and from 1651 onward the English were established as traders alike on the seaboard and in the interior of Bengal. These trading posts were at Balasor, and perhaps at Pippli on the Orissa coast; at Hugli, Kasimbazar near Murshidabad, and one or two out-stations in the Ganges delta; and at Patna and subordinate agencies higher up the Ganges, in Behar.

All would not go well at the Bengal outposts (“factories”), however. Page 246 continues thus:

It soon appeared that this advance northward exceeded the still feeble powers of the Company. The Bengal factories lay beyond effective control. Their staff, in spite of all pious instructions, plunged into irregularities which ended in two of them deserting the Company’s service, in the death of a third ruined by debt, and in the return of a fourth to Madras with a story that he had lost the Company’s papers. The good surgeon Boughton was also dead, and his widow, who had married again, was clamouring for a reward for his services. In 1656–1657 the Madras Council for the second time withdrew, or resolved to withdraw, their factories from the Bengal seaboard.