In international affairs, the Peace of Westphalia that was concluded among numerous, European-only parties in 1648 CE set the basic rules of inter-state conduct that are still fundamentally in place, covering the entire world of humankind, until today. Already in 1648, four European states had extensive transoceanic empires through which they were able to affect the balance of power in many non-European parts of the world. Over the decades and centuries that followed 1648, the power that a handful of European states were able to wield– and did wield– over the non-European world increased greatly. In some ways, the Peace of Westphalia enabled that to happen, primarily because after 1648 the two most powerful European imperial powers at that time, Spain and Netherlands, no longer had to fight each to the death at home.

Nonetheless, in the context of today’s politics in 2021, I am a staunch Westphalian. (See what I wrote on the topic nearly two years ago, here.) What this means for me as a U.S. citizen, is primarily that I oppose all attempts by my government or by actors in the U.S. political system to intervene in any way in the internal affairs of other countries.

Well I’m happy to discuss that elsewhere. Here, I need to track and summarize what the 1648 Peace of Westphalia was and what it meant at the time.

In terms of how I’ll organize today’s bulletin, I’ll start with two short items of world news from 1648, proceed through a quick foray into England’s Second Civil War (probably taking that up to the execution of King Charles I in January 1649), and then look at Westphalia and what it wrought.

Short takes

1. More turmoil in Topkapi

Sultan Ibrahim of the Ottoman Empire, who’d been raised in a cage in the harem because of his older brother’s distrust of him and was probably barking mad, had been Sultan since 1640. In 1644 he got the Empire into a war against Venice, whose navy was able to block the waterway of the Dardanelles which was essential to Istanbul’s ability to connect with trade (or warmaking) routes in the Mediterranean. He engaged in lots of (often deadly) infighting in the palace and at one point ordered that the palace of one of his opponents be carpeted in sable furs and given to one of his favorite concubines.

In 1648, the Janissaries and members of the ulema revolted. WP tells us:

On 8 August 1648, corrupt Grand Vizier Aḥmed Pasha was strangled and torn to shreds by an angry mob, gaining the posthumous nickname “Hezarpare” (“thousand pieces”). On the same day, Ibrahim was seized and imprisoned in Topkapı Palace. [His powerful mother] Kösem gave consent to her son’s fall, saying “In the end he will leave neither you nor me alive. We will lose control of the government. The whole society is in ruins. Have him removed from the throne immediately.”

Ibrahim’s six-year-old son Meḥmed was made sultan. The new grand vizier, Ṣofu Meḥmed Pasha, petitioned the sheikh ul-Islam for a fatwā sanctioning Ibrahim’s execution. It was granted, with the message “if there are two caliphs, kill one of them.” Kösem also gave her consent. Two executioners were sent for; one being the chief executioner who served under Ibrahim. As officials watched from a palace window, Ibrahim was strangled on 18 August 1648. His death was the second regicide in the history of the Ottoman Empire.

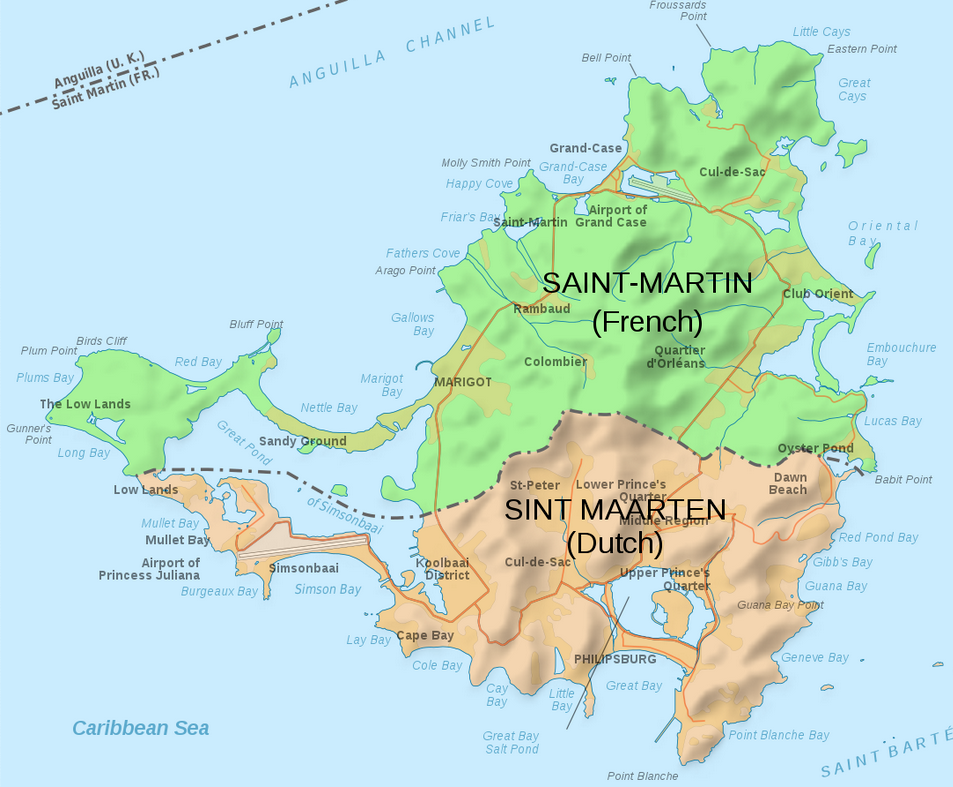

2. France and Netherlands divide St. Martin island

St. Martin is a tiny speck of an island (34 sq. miles) in the northeast of the Antilles chain, once populated by Arawaks and Caribs. The Spanish had controlled it for a long time. But with Spanish power waning, the Dutch had come in at some point. It is clear that the 1630s and 1640s were a time when the European transoceanic powers were seeing slave-worked Caribbean sugar plantations as the next big profit-making thing. So France had come here as well. And in 1648 the Dutch and French agreed to split the island. The story of how they did this is quite amusing if you want to read it.

Anyway, I record this here because it is another sign of France’s still-sputtering entry into the empire-building stakes. (Also, see the last item below.)

England’s Second Civil War leads to Charles’s beheading

When we left the English Civil War at the end of 1647, King Charles I had just escaped from Parliamentary imprisonment and headed for Carrisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight. He was king of both England and Scotland (a separate country) and he used his time at liberty to negotiate a deal with the Scottish “Covenanters” who were Protestant Presbyterians opposed both to the bishop-based system of church government in the Church of England and to the more radical populism of the Levellers, Diggers, and so on, often classified as the “Independents”. Those latter factions were strong in the New Model Army, while the Presbyterians were over-represented in the English as well as Scottish parliament.

Wikipedia takes this complex story forward:

In April 1648, [Charles’s] supporters gained a majority in the Parliament of Scotland and agreed to restore Charles to the English throne. In return, he undertook to impose Presbyterianism in England for three years, and suppress the Independents, a pact known as ‘The Engagement’. However, his refusal to take the Covenant himself split the Scots between those who backed the agreement, known as Engagers, and the Kirk Party, who denounced it as ‘sinful’. However, Charles finally had the pieces in place for a rising by Scots and English Royalists, supported by some English Presbyterians, and Scots Covenanters.

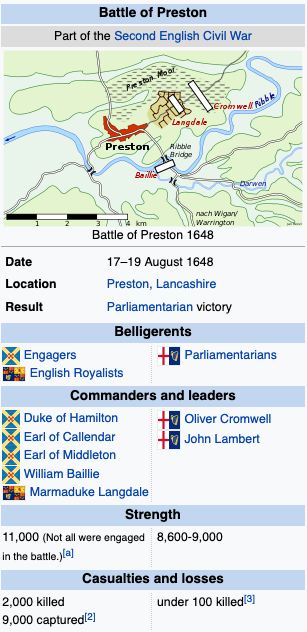

There followed pro-Royalist uprisings in many Parliament-held areas of England and Wales. You can read all the details here. Parliament’s New Model Army really showed the effectiveness of its training and organization. The final, decisive battle of this phase of the war was fought at Preston in Lancashire over the last two weeks of August, resulting in a Parliamentary victory.

Charles was still in the Isle of Wight; and after the Parliamentary victory at Preston the Parliamentary leaders resumed negotiating with him. Some of them still hoped he might meet their terms and be able to stay in office in a more tightly circumscribed monarchy. However, the Parliamentary faction opposed to giving him yet another chance had grown. Then, per this page on WP, this happened:

On 5 December 1648, Parliament voted by 129 to 83 to continue negotiating with the king, but Oliver Cromwell and the army opposed any further talks with someone they viewed as a bloody tyrant and were already taking action to consolidate their power. [Isle of Wight Governor Robert] Hammond was replaced as Governor of the Isle of Wight on 27 November, and placed in the custody of the army the following day. In Pride’s Purge on 6 and 7 December, the members of Parliament out of sympathy with the military were arrested or excluded by Colonel Thomas Pride, while others stayed away voluntarily. The remaining members formed the Rump Parliament. It was effectively a military coup.

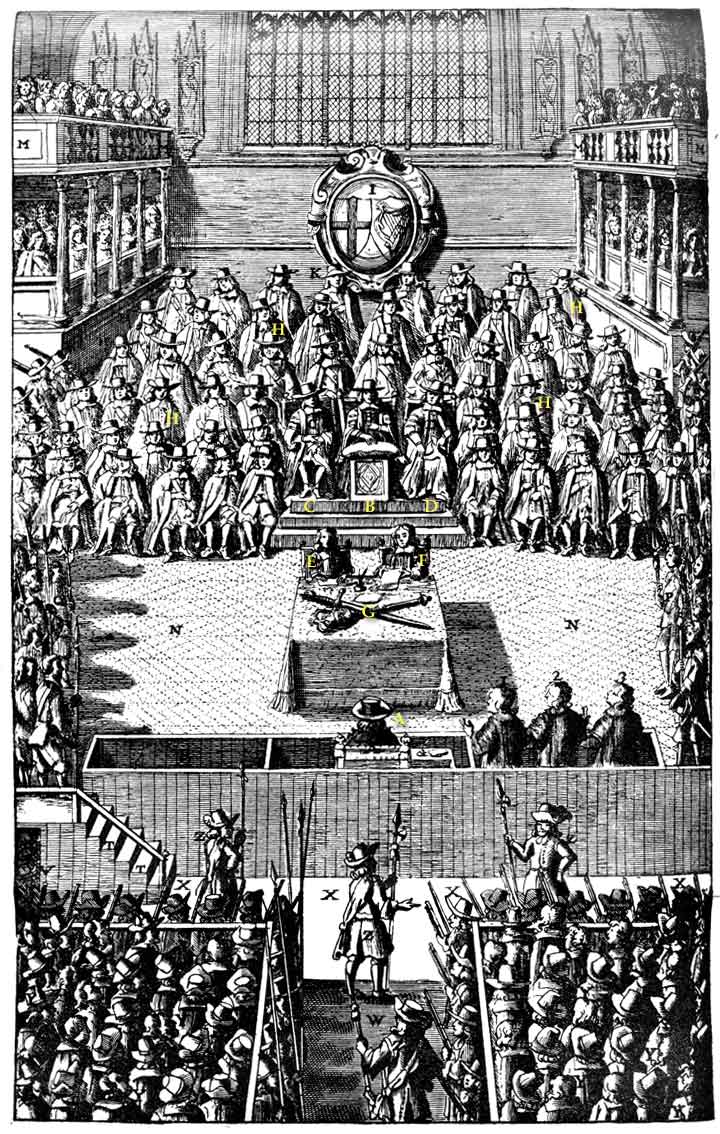

The NMA moved Charles to Windsor Castle. In January 1649, the Rump House of Commons indicted him on a charge of treason, which was rejected by the House of Lords. So then the House of Commons established a special, 135-member High Court of Justice to hear the case against him. It started its work on January 20, 1649:

Charles was accused of treason against England by using his power to pursue his personal interest rather than the good of the country. The charge stated that he, “for accomplishment of such his designs, and for the protecting of himself and his adherents in his and their wicked practices, to the same ends hath traitorously and maliciously levied war against the present Parliament, and the people therein represented”, and that the “wicked designs, wars, and evil practices of him, the said Charles Stuart, have been, and are carried on for the advancement and upholding of a personal interest of will, power, and pretended prerogative to himself and his family, against the public interest, common right, liberty, justice, and peace of the people of this nation.” Presaging the modern concept of command responsibility, the indictment held him “guilty of all the treasons, murders, rapines, burnings, spoils, desolations, damages and mischiefs to this nation, acted and committed in the said wars, or occasioned thereby.” An estimated 300,000 people, or 6% of the population, died during the war.

Over the first three days of the trial, whenever Charles was asked to plead, he refused, stating his objection with the words: “I would know by what power I am called hither, by what lawful authority…?” He claimed that no court had jurisdiction over a monarch, that his own authority to rule had been given to him by God and by the traditional laws of England, and that the power wielded by those trying him was only that of force of arms.

On January 26, 1649, he was found guilty and condemned to death. Four days later he was beheaded. With the monarchy overthrown, England became a republic or “Commonwealth”. The House of Lords was abolished by the Rump Commons, and executive power was assumed by a Council of State.

In Westphalia, Spain recognizesDutch independence & Europe ends its 30-Year War

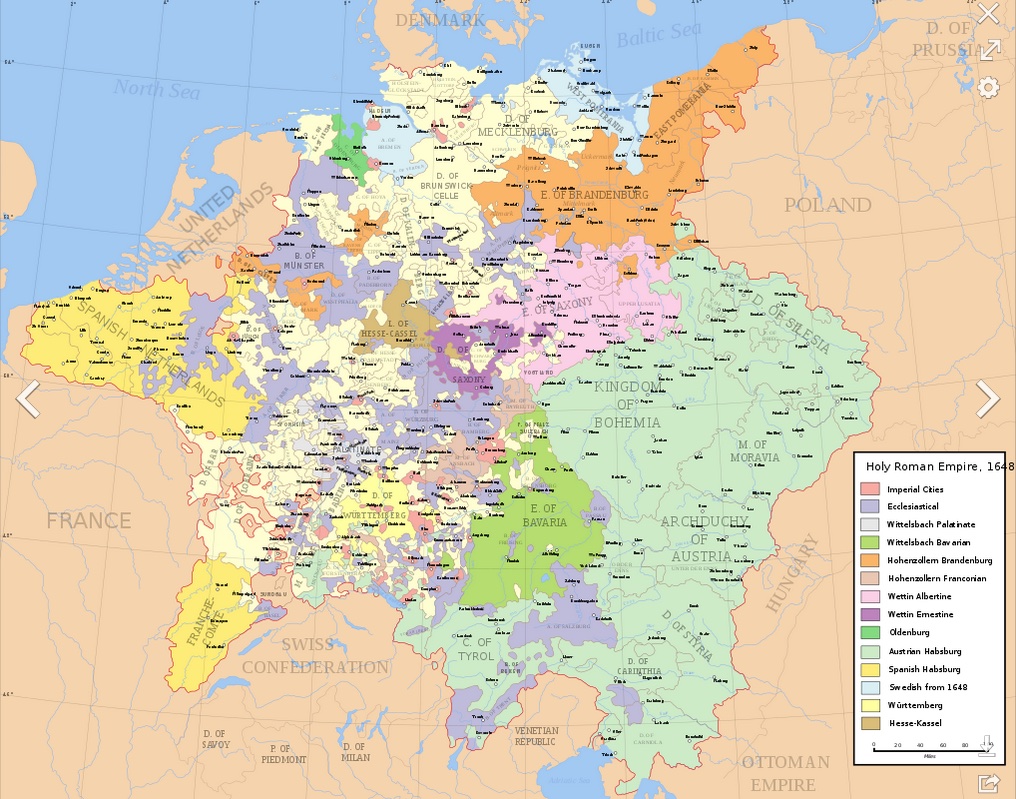

The Thirty Years’ War had been mainly an attempt by Catholic Spain, its close ally the (Austro-Hungarian) Habsburg “Holy Roman Empire” and the dependencies of these two powers scattered all across central Europe to crush the growing power (primarily in Europe but also worldwide) of Protestant states like Netherlands, England, and Sweden.

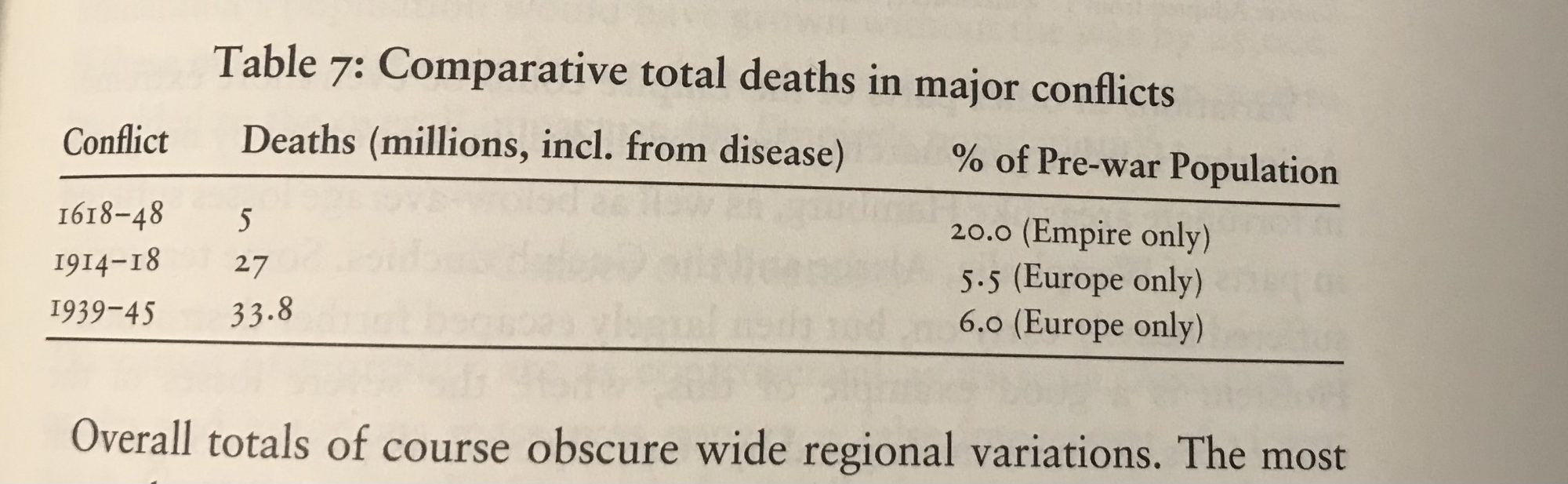

The war was extremely costly in lives and treasure. In his massive 2009 study of the war, British historian Peter H. Wilson estimated that 20% of the Habsburg Empire’s population had died during it (including from disease, which as we all know is always far more rampant and deadly in situations of prolonged war.) That, compared with 5.5% of Europe’s population dying during World War I and 6.0% during World War II. (Table, p.787, as shown.)

For many years prior to 1648, numerous different combinations of envoys, alliances, and coalitions had been testing the chances of bringing the conflict to an end. In the end, this happened in 1648, in two peace treaties signed in different cities in the northwest German province of Westphalia.

This WP page on the Peace of Westphalia gives us the following background:

The negotiation process was lengthy and complex. Talks took place in two cities, because each side wanted to meet on territory under its own control. A total of 109 delegations arrived to represent the belligerent states, but not all delegations were present at the same time. Two treaties were signed to end each of the overlapping wars: the Peace Treaty of Münster and the Peace Treaty of Osnabrück.These treaties ended the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) in the Holy Roman Empire, with the Habsburgs (rulers of Austria and Spain) and their Catholic allies on one side, battling the Protestant powers (Sweden, Denmark, and certain Holy Roman principalities) allied with France, which was Catholic but strongly anti-Habsburg under King Louis XIV.

… In Münster, negotiations took place between the Holy Roman Empire and France, as well as between the Dutch Republic and Spain who on 30 January 1648 signed a peace treaty, that was not part of the Peace of Westphalia. Münster had been, since its re-Catholicisation in 1535, a strictly mono-denominational community. It housed the Chapter of the Prince-Bishopric of Münster. Only Roman Catholic worship was permitted, while Calvinism and Lutheranism were prohibited.

Sweden preferred to negotiate with the Holy Roman Empire in Osnabrück, controlled by the Protestant forces. Osnabrück was a bidenominational Lutheran and Catholic city, with two Lutheran churches and two Catholic churches. The city council was exclusively Lutheran, and the burghers mostly so, but the city also housed the Catholic Chapter of the Prince-Bishopric of Osnabrück and had many other Catholic inhabitants. Osnabrück had been subjugated by troops of the Catholic League from 1628 to 1633 and then taken by Lutheran Sweden.

The peace negotiations had no exact beginning or end, because the 109 delegations never met in a plenary session. Instead, various delegations arrived between 1643 and 1646 and left between 1647 and 1649. The largest number of diplomats were present between January 1646 and July 1647.

Delegations had been sent by 16 European states, 66 Imperial States representing the interests of 140 Imperial States, and 27 interest groups representing 38 groups.

…

Three separate treaties constituted the peace settlement:

** The Peace of Münster was signed by the Dutch Republic and the Kingdom of Spain on 30 January 1648, and was ratified in Münster on 15 May 1648.

**Two complementary treaties were signed on 24 October 1648: The Treaty of Münster… between the Holy Roman Emperor and France, along with their respective allies, [and] The Treaty of Osnabrück… between the Holy Roman Empire and Sweden, along with their respective allies.

The banner image at the top here is a famous painting of signatories swearing the oath of ratification of the Treaty of Munster by Gerard ter Borch. He painted himself grinning out from the left side of it.

In 1648, the (Austro-Hungarian) “Holy Roman Emperor” was Ferdinand III. Between them, he and the Spanish king, Philip IV, who was also from the “Habsburg” line, had claimed jurisdiction over hundreds of tiny statelets and city-states dotted all through present-day Germany. Under the Peace of Westphalia, the power to rule these “imperial states” was stripped from Ferdinand and returned to (or vested in) the rulers of the states themselves– and these rulers could henceforth choose their own official religions! “Catholics and Protestants were redefined as equal before the law, and Calvinism was given legal recognition as an official religion. The independence of the Dutch Republic, which practiced religious toleration, also provided a safe haven for European Jews.”

Not surprisingly, the Vatican hated all this tolerance of freethinking. Pope Innocent X (who wasn’t) did not mince words, describing it as: “null, void, invalid, iniquitous, unjust, damnable, reprobate, inane, empty of meaning and effect for all time.”

English-WP summarized the tenets of the Westphalian Peace as follows:

** All parties would recognise the Peace of Augsburg of 1555, in which each prince would have the right to determine the religion of his own state (the principle of cuius regio, eius religio). The options were Catholicism, Lutheranism, and now Calvinism.

** Christians living in principalities where their denomination was not the established church were guaranteed the right to practice their faith in private, as well as in public during allotted hours.

** France and Sweden were recognised as guarantors of the imperial constitution with a right to intercede. [I am not sure at all what this means.]

** It is often argued that the Peace of Westphalia resulted in a general recognition of the exclusive sovereignty of each party over its lands, people, and agents abroad, as well as responsibility for the warlike acts of any of its citizens or agents.

It seems the editors at Wikipedia had some disagreement over the contribution that the 1648 peace treaties of Westphalia actually made to the concept of “Westphalian sovereignty” that emerged over the decades and centuries that followed.

This other WP page, on “Westphalian Sovereignty”, summarizes the concept thus:

Westphalian sovereignty, or state sovereignty, is a principle in international law that each state has exclusive sovereignty over its territory. The principle underlies the modern international system of sovereign states and is enshrined in the United Nations Charter, which states that “nothing … shall authorize the United Nations to intervene in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state.” According to the idea, every state, no matter how large or small, has an equal right to sovereignty. Political scientists have traced the concept to the Peace of Westphalia (1648), which ended the Thirty Years’ War. The principle of non-interference was further developed in the 18th century. The Westphalian system reached its peak in the 19th and 20th centuries, but it has faced recent challenges from advocates of humanitarian intervention.

A Swedish push into Prague

This is an interesting side-eddy in the grander scheme of things, but it does help explain what the delay was between the conclusion of the Dutch-Spanish treaty in January 1648 and the broader (two-headed) Peace of Westphalia in October.

We’ve noticed Sweden quite a bit in recent years. The famous King Gustavus Adolphus had taken Sweden into the Thirty Years War as a big force on the Protestant side. He died in 1632 and was succeeded by his 6-year-old daughter Christina. Sweden was ruled by a regent called Count Axel Oxenstierna until she was 18 (1644.) He was much more hawkishly anti-Spanish than she, but by 1648 she was able to prevail and gave Sweden’s support to the Peace of Westphalia. By then, Sweden had a large troop presence in Germany (including many locally-hired German mercenaries.)

But in late summer of 1648 this happened:

The Battle of Prague, which occurred between 25 July and 1 November 1648 was the last action of the Thirty Years’ War. While the negotiations for the Peace of Westphalia were proceeding, the Swedes took the opportunity to mount one last campaign into Bohemia. The main result, and probably the main aim, was to loot the fabulous art collection assembled in Prague Castle by Rudolph II, Holy Roman Emperor (1552–1612), the pick of which was taken down the Elbe in barges and shipped to Sweden.

After occupying the castle and the western bank of the Vltava for some months, the Swedes stopped assaulting the Old and New Town at the eastern bank when news of the signing of the treaty reached them. They still remained a garrison on the western bank until their final withdrawal on 30 September 1649.

It was the last major clash of the Thirty Years’ War, taking place in the city of Prague, where the war originally began 30 years earlier.

The Spanish-Dutch Peace

From the perspective of world history/ geopolitics, probably the most important direct effect of the intra-European diplomacy of 1648 was the conclusion of the peace between Spain and Netherlands, which brought to an end a conflict that had continued for 80 years by then– ever since the first Protestant Dutch rebels had started defying the authorities in what was then still Spanish-ruled Netherlands.

This page on WP lays out some of what was at stake:

The Dutch Revolt, also called the Eighty Years’ War, of 1568–1648 was the struggle by the Seven United Provinces of the Netherlands for independence from the Spanish Empire. Spain [in 1568] was at the height of its power and initially suppressed the rebellion, but in 1572 the Dutch rebels captured the strategic port of Brielle, providing them with a bridgehead for rapidly expanding the area under their control. Supported by France and Protestant states like England and Scotland, by 1581 the Northern provinces of the Netherlands were de facto independent. By the mid-17th century the Netherlands was the world’s leading economic and maritime power, a period of economic, scientific and cultural growth later known as the Dutch Golden Age.

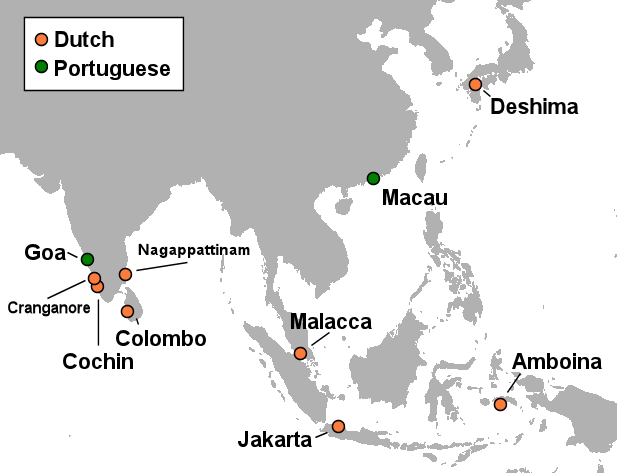

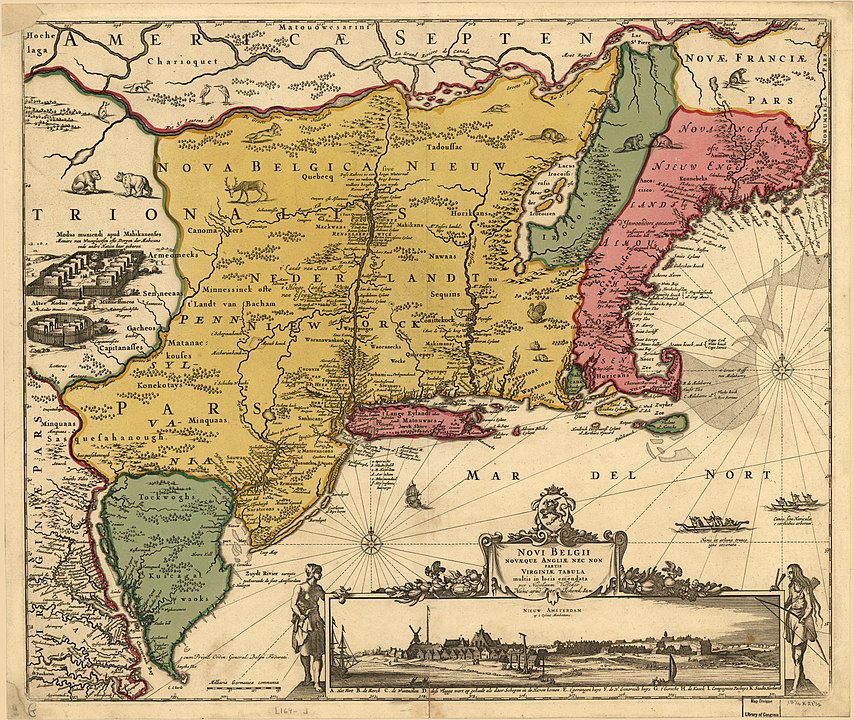

The speed and extent of the rise of the Netherlands’ emergence as a world empire in those decades is definitely worth noting– equalled only by the explosive entry Spain had made onto the world scene in the decades after 1492.

WP continues:

Despite these successes, the Dutch failed to expel the Spanish from the wealthy provinces of the Southern Netherlands, modern-day Belgium, Luxembourg plus the Nord-Pas-de-Calais and Longwy regions of northern France. France had financed the Dutch for many years to weaken the Habsburgs, then the dominant power in Europe; after the Treaty of Prague in 1635 it formally declared war on Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. In 1639, the Dutch navy destroyed a Spanish fleet carrying supplies and men to the Netherlands at the Battle of the Downs while in 1643 the French defeated the Army of Flanders at the Battle of Rocroi.

More signs of Spain’s 17th-century decline there– as we have seen already in recent years with the loss of its base in Taiwan, and of course the 1640 secession of Portugal.

More WP:

French intervention and internal discontent at the costs of the Dutch war led to a change in Spain’s ‘Netherlands First’ policy and a focus on suppressing the French-backed Catalan Revolt or Reapers War. After Rocroi, France acquired large parts of the Southern Netherlands and Dutch leaders like Andries Bicker and Cornelis de Graeff grew concerned the main beneficiary of continuing the war was France. These fears were heightened by suggestions of a treaty between Spain and France that would be reinforced by a marriage between Louis XIV and a daughter of Philip IV. Such an outcome threatened the Dutch since France would acquire dynastic rights over the Southern Netherlands and potentially the Northern provinces as well. These factors increased the urgency on both sides to end the war.

So then, both Spain and Netherlands were motivated to find a way to bring their 80-year conflict finally to an end. They had had a 12-year truce along the way, remember, between 1609 and 1621. But that truce always had the time-limit; and crucially, in concluding it, the Spanish side still steadfastly refused to recognize that Netherlands had any “right” to independence. This time, in 1648, it finally did… Well, kinda/almost… WP says this: “While Spain did not recognise the Dutch Republic, it agreed that the Lords States General of the United Netherlands was ‘sovereign’ and could participate in the peace talks.”

Oh and by the way, with England still in civil war, the Dutch felt they were in a great place to push against England’s interests in the West Indies, North America, and elsewhere…