In 1642 CE, the main developments of geopolitical impact were the civil wars in both ultra-large China and tiny England. The significance of the latter was magnified because by then, England already had a globe-girdling empire with non-trivial positions in India, North America, and the Caribbean; and the outcome of the struggle for power “back home” between King and parliament that first erupted in earnest in 1642 would strongly affect the workings of the empire. China’s civil war had been running for many years by 1642 but in that year it was heading toward its end-game and saw the commission by fast-failing Ming forces of a terrifying mass atrocity. (Scroll on down for details.)

Another somewhat significant development in 1642 was that the Dutch VOC, now well established on the south and west of Formosa/Taiwan, finally ousted from the north of the island the Spanish fortified position that had been there some years, pushing the influence that “New Spain” could exert in East Asia back to the Philippines.

In this bulletin, I’ll focus first on the English civil war and a significant ramification/extension of its in Ireland, then we’ll travel to East Asia.

England’s King Charles provokes parliament into rebellion

When we left the English scene last year, Parliament had just issued the “Grand Remonstrance” detailing the 204 demands it was making of King Charles; and at the end of December 1641 Charles had refused one of its key demands, the removal of bishops accused of being “too Catholic”…

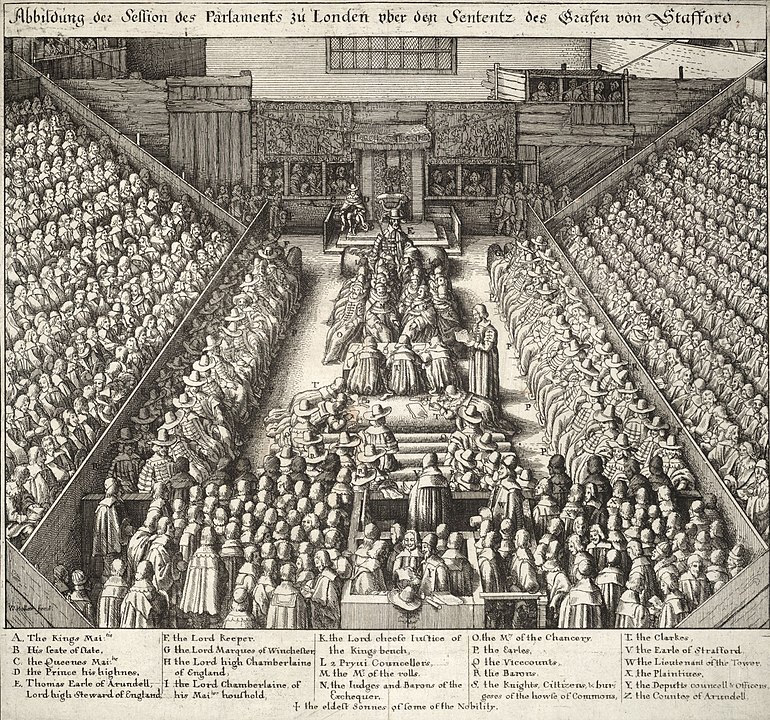

On January 3, 1642, he struck back, as this WP page informs us:

Charles directed Parliament to give up five members of the Commons – [John] Pym, John Hampden, Denzil Holles, William Strode and Sir Arthur Haselrig – and one peer – Lord Mandeville – on the grounds of high treason. When Parliament refused, it was possibly [his Catholic queen] Henrietta Maria who persuaded Charles to arrest the five members by force, which Charles intended to carry out personally. However, news of the warrant reached Parliament ahead of him, and the wanted men slipped away by boat shortly before Charles entered the House of Commons with an armed guard on 4 January. Having displaced the Speaker, William Lenthall, from his chair, the king asked him where the MPs had fled. Lenthall, on his knees, famously replied, “May it please your Majesty, I have neither eyes to see nor tongue to speak in this place but as the House is pleased to direct me, whose servant I am here.” Charles abjectly declared “all my birds have flown”, and was forced to retire, empty-handed.

The botched arrest attempt was politically disastrous for Charles. No English sovereign had ever entered the House of Commons, and his unprecedented invasion of the chamber to arrest its members was considered a grave breach of parliamentary privilege. In one stroke Charles destroyed his supporters’ efforts to portray him as a defence against innovation and disorder.

Matters swiftly escalated. This other WP page tells us:

Over the winter of 1641 to 1642, many towns strengthened their defences, and purchased weapons, although this was not necessarily in response to fears of conflict between Charles and his Parliament. Lurid details of the 1641 Irish Rebellion meant many were more concerned by reports of a planned Catholic invasion.

Although both sides supported raising troops to suppress the Irish rising, alleged Royalist conspiracies to use them against Parliament meant neither trusted the other with their control. When Charles left London after failing to arrest the Five Members in January 1642, he handed Parliament control of the largest city, port and commercial centre in England, its biggest weapons store in the Tower of London, and best equipped local militia, or Trained bands.

Founded in 1572, these were organised by county, controlled by Lord-lieutenants appointed by the king, and constituted the only permanent military force in the country. The muster roll of February 1638 shows wide variations in size, equipment and training; Yorkshire had the largest, with 12,000 men, followed by London with 8,000, later increased to 20,000. ‘Royalist’ counties like Shropshire or Glamorgan had fewer than 500 men.

In March 1642, Parliament approved the Militia Ordinance, claiming control of the trained bands; Charles responded with his own Commissions of Array. More important than the men were the local arsenals, with Parliament holding the two largest in London, and Hull. These belonged to the local community, who often resisted attempts to remove them, by either side. In Royalist Cheshire, the towns of Nantwich, Knutsford and Chester declared a state of armed neutrality, and excluded both parties.

Ports were vital for access to internal and external waterways, the primary method of importing and transporting bulk supplies until the advent of railways in the 19th century. Most of the Royal Navy declared for Parliament, allowing them to protect the trade routes vital to the London merchant community and block Royalist imports. It also made other countries wary of antagonising one of the strongest navies in Europe by providing support to their opponents. By September, forces loyal to Parliament held every major port in England apart from Newcastle, which prevented Royalist areas in Wales, South-West and North-East England from supporting each other. In February 1642, Charles sent his wife, Henrietta Maria, to the Hague to raise money and purchase weapons; lack of a secure port delayed her return until February 1643, and even then, she narrowly escaped capture.

Both sides expected a single battle and quick victory; for the Royalists, this meant capturing London, for Parliament, ‘rescuing’ the king from his ‘evil counsellors.’

Oh, isn’t that ever the case: that at the beginning of almost all such conflicts, “both sides expect a single battle and quick victory.”

Charles had clearly made a number of grave mistakes. One was provoking parliament without understanding how steeply the balance of forces was arrayed against him. Another was leaving London (and its arsenal and its rich merchant community) almost immediately after the showdown over the Five Members.) He tried but failed to take control of the northeastern seaport of Hull then came with his people down to Nottingham in the more Royalist English Midlands. WP tells us on this page that: “Particularly in the early stages of the conflict, locally raised troops were reluctant to serve outside their own county, and most of the Royalist troops raised in Yorkshire refused to accompany him.” So he really looked pretty disorganized.

On August 22, in Nottingham, he formally declared war on the parliamentary rebels:

but by early September his army consisted of only 1,500 horse and 1,000 infantry, with much of England hoping to remain neutral. Financing from the London mercantile community and weapons from the Tower enabled Parliament to recruit and equip an army of 20,000. It was commanded by the Presbyterian Earl of Essex, who left London on 3 September for Northampton.

Back to the WP page on Charles I which tells us that by late August 1642,

Charles’s forces controlled roughly the Midlands, Wales, the West Country and northern England. He set up his court at Oxford. Parliament controlled London, the south-east and East Anglia, as well as the English navy.

After a few skirmishes, the opposing forces met in earnest at Edgehill, on 23 October 1642. Charles’s nephew Prince Rupert of the Rhine disagreed with the battle strategy of the royalist commander Lord Lindsey, and Charles sided with Rupert. Lindsey resigned, leaving Charles to assume overall command assisted by Lord Forth. Rupert’s cavalry successfully charged through the parliamentary ranks, but instead of swiftly returning to the field, rode off to plunder the parliamentary baggage train. Lindsey, acting as a colonel, was wounded and bled to death without medical attention. The battle ended inconclusively as the daylight faded.

In his own words, the experience of battle had left Charles “exceedingly and deeply grieved”. He regrouped at Oxford, turning down Rupert’s suggestion of an immediate attack on London. After a week, he set out for the capital on 3 November, capturing Brentford on the way while simultaneously continuing to negotiate with civic and parliamentary delegations. At Turnham Green on the outskirts of London, the royalist army met resistance from the city militia, and faced with a numerically superior force, Charles ordered a retreat. He overwintered in Oxford, strengthening the city’s defences and preparing for the next season’s campaign. Peace talks between the two sides collapsed in April [1643].

So we’ll leave Charles there in Oxford. As the Civil War continues over the next few years I’ll be tracking in particular which way the merchants and investors of London and other port cities who were the main motor of England’s imperial ventures were trending, as well as the role of the Puritans who were a big political force in England, Scotland, and North America.

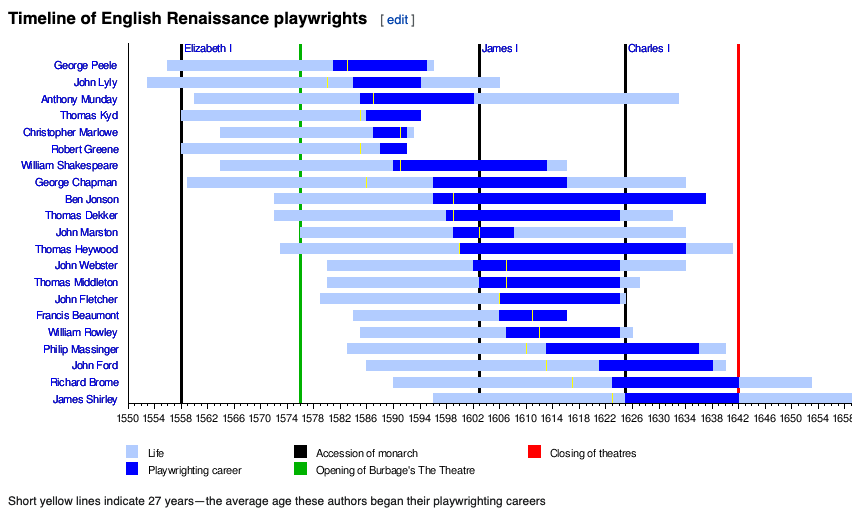

Talking of whom, one of the first acts that the newly self-confident Parliament in London took in 1642 was to close down the whole theatrical scene that had flourished there since the 1580s and that the Puritans viewed with grave disapproval. And over in North America, in 1642 the New Haven Colony executed a man for alleged bestiality and so did the Plymouth Colony. The man executed in Plymouth, Thomas Granger, was the first juvenile executed in the Anglo-colonized parts of today’s United States. The acts for which he was executed make, um, interesting reading.

Birth of the Irish Catholic Confederacy

Here‘s the short version:

Confederate Ireland was the period of Irish Catholic self-government between 1642 and 1649, during the Eleven Years’ War. During this time, two-thirds of Ireland was governed by the Irish Catholic Confederation or Confederacy, also known as the Confederation of Kilkenny because it was based in Kilkenny. It was formed by Catholic nobles, landed gentry, clergy and military leaders after the Irish Rebellion of 1641, and it included Catholics of Gaelic and Anglo-Norman descent. They wanted an end to anti-Catholic discrimination within the kingdom of Ireland, greater Irish self-governance, and to roll back the plantations of Ireland. They also wanted to prevent an invasion by anti-Catholic English Parliamentarians and Scottish Covenanters, who were defying the king, Charles I. Most Confederates professed loyalty to Charles I and believed they could reach a lasting settlement with the king once his opponents in the English Civil War had been defeated. The Confederacy had what were effectively a parliament (called the General Assembly), an executive (called the Supreme Council), and a military. It minted coins, levied taxes and set up a printing press. Confederate ambassadors were appointed and recognised in France, Spain and the Papal States, who supplied the Confederates with money and weapons…

The first Confederate General Assembly, containing 251 members from all parts of Ireland, was held in Kilkenny on 24 October 1642, and set up a provisional government. But they never claimed to be an independent government– because they were Royalists. Charles, however, was extremely wary of their expressions of support:

The difficulty for Charles was that he was horrified at the 1641 rebellion [in Ireland] and had signed the Adventurers Act into law in 1642, which proposed confiscating all rebel held lands in Ireland. A new policy of refusing pardon to any Irish rebels had also been agreed in London and Dublin (issuing pardons had been a common method to end Irish conflicts in the previous century). Therefore, his forces remained hostile to the Confederates until 1643, when his military position in England started to weaken. Many of the Confederate gentry stood to lose their land under the Adventurers Act; it galvanised their efforts and they realised that it could only be repealed by taking a loyal stance.

However, while the moderate Confederates were anxious to come to an agreement with Charles I and did not press for radical political and religious reforms, others wished to force the King to accept a self-governing Catholic Ireland before they came to terms with him. Failing that, they advocated an independent alliance with France or Spain.

Complicated! What with all those developments in Ireland and the ongoing issues in Scotland, many people refer to the English Civil War as the “Wars of the Three Kingdoms” instead.

Peasant rebellion sweeps across central China; Ming respond with dam-busting atrocity

I’ve written quite a lot in earlier bulletins about Hong Taiji, the leader of the ‘Later Jin’, now “Qing” dynasty, who’s been lurking in the north of the country amassing power and will soon be reaching Beijing. But not yet. For now, the main threat that China’s decadent and fading Ming dynasty sees is the massive peasant rebellion sweeping in from the west that is led by an illiterate guy called Li Zicheng. Born in northeast Shaanxi province in 1606, Li’s first reputed act of rebellion had occurred in 1630, Li was,

put on public display in an iron collar and shackles for failing to repay loans to a usurious magistrate. The magistrate, a man by the name of Ai, struck a guard who tried to give Li shade and water. A group of sympathetic peasants freed Li from his shackles, spirited him to a nearby hill, and proclaimed him their leader. Although they were only armed with wooden sticks, Li and his band managed to ambush a group of government soldiers sent to arrest them, and obtained their first real weapons…

Then this:

In 1633, Li joined a rebel army led by Gao Yingxiang, nicknamed “Dashing King.” He inherited Gao’s nickname and command of the rebel army after Gao’s death. Within three years, Li succeeded in rallying more than 30,000 men to form a rebel army. They attacked and killed prominent government officials… in the Henan, Shanxi, and Shaanxi provinces. As Li won more battles and gained more support, his army grew larger. Historians attribute this growth in numbers to Li’s reputation as a Robin Hood style figure who showed compassion to the poor and only attacked Ming officials.

By 1642, Li’s peasant army was besieging Kaifeng, a large city located on the banks of the yellow River at a location prone to flooding. This WP page tells us that, “By the mid-15th century, the Ming had completed restoration of the area’s flood-control system and operated it with general success for over a century.”

When Li’s forces had besieged the city for six months, it seems** it was Kaifeng’s Ming governor who broke the dykes and dams of the flood-control system…

in an attempt to flood the rebels, but the water destroyed Kaifeng. Over 300,000 of the 378,000 residents were killed by the flood and ensuing peripheral disasters such as famine and plague. After this disaster the city was abandoned until 1662.

** One of the WP pages I consulted said the Kaifeng dykes were breached “by both sides”, citing this source. But I’m not sure this makes any sense?

And another small item about the Kaifeng flood: “The flood also brought an end to the “golden age” of the Jewish settlement of China, said to span about 1300–1642. China’s small Jewish population, estimated at around 5,000 people, was centered at Kaifeng.”

(The banner image at the head of this post is an 18th century reproduction of a 12th century painting of a festival at Kaifeng.)

Dutch oust Spanish from Formosa

Alert readers will recall that in 1633, the Dutch VOC commander based in southwestern Taiwan had reached a workable trade agreement with the Ming admiral after a couple of sea-battles on the other side of the Taiwan Strait… and that the Spanish still had a small fort on the northern coast of Taiwan, at Keelung.

In 1641, the Dutch had launched a naval campaign to oust the Spanish from their base, called “San Salvador”, but it failed. In 1642, they tried again, bringing in four larger ships, several smaller ones, and 369 Dutch soldiers. The Spanish-led force defending San Salvador consisted of 60 Spanish and Filipino soldiers and 30-40 fighters described as “aboriginal warriors”– presumably, Indigenous Taiwanese.

Long story short, the Spanish eventually surrendered. Then this:

After the surrender, the Dutch confiscated the Spanish arms and flags and ferried the Spanish troops first to Tayouan, then to Batavia, and then finally back to Manila. The Dutch victory cemented their status as a rising power in Southeast Asia and curtailed further Spanish expansion. In the meantime, the Spanish quarreled about who deserved blame for the loss of Formosa.