The three most notable developments of 1636 CE all took place in Asia. They were: The adoption by the Tokugawa shogunate in Japan of the policy of Sakoku (鎖国, “closed country”); the announcement by Hong Taiji, leader of northern China’s “Later Jin” movement of a new imperial dynasty, the Qing dynasty; and the arrival in Surat, India, of an English rival to the East India Company (EIC.) Here are more details and more context.

Japan’s shoguns close the country to foreign trade, influence

The powerful shogun Tokugawa Iemetsu had been working for some years to curtail and control all trade and other forms of contact between Japan and other countries– in contrast to his father (and predecessor) who had sent an emissary to many parts of Europe back in the years 1613-1618. Japan, not surprisingly, had considerable maritime expertise; and for generations past Japanese merchantment, mariners, and pirates had been part of the fabric of trade and interaction in the seas of East Asia. In the mid-16th century, Japan’s emperors and shoguns had been early adopters of the skills in casting large bronze cannons that the Portuguese brought to the region, and many thousands of people in southern Japanese had adopted the Catholic Christianity brought by Portugal’s Jesuits and other missionaries.

Under Iemetsu, all that changed. And indeed, the “Sakoku” (Seclusion) edicts he introduced in the mid-1630s would continue to govern all of Japan’s foreign dealings until 1854.

On this page on English-WP on the Sakoku policy, the editors present two different accounts of the reasoning behind it:

It is conventionally regarded that the shogunate imposed and enforced the sakoku policy in order to remove the colonial and religious influence of primarily Spain and Portugal, which were perceived as posing a threat to the stability of the shogunate and to peace in the archipelago…

The motivations for the gradual strengthening of the maritime prohibitions during the early 17th century should [also] be considered within the context of the Tokugawa bakufu’s [basically, its bureaucracy] domestic agenda. One element of this agenda was to acquire sufficient control over Japan’s foreign policy so as not only to guarantee social peace, but also to maintain Tokugawa supremacy over the other powerful lords in the country, particularly the tozama daimyōs [magnates/merchants.] These daimyōs had used East Asian trading linkages to profitable effect during the Sengoku period, which allowed them to build up their military strength as well.

That same WP page presents the content of the Seclusion edict of 1636 as follows:

No Japanese ship … nor any native of Japan, shall presume to go out of the country; whoever acts contrary to this, shall die, and the ship with the crew and goods aboard shall be sequestered until further orders. All persons who return from abroad shall be put to death. Whoever discovers a Christian priest shall have a reward of 400 to 500 sheets of silver and for every Christian in proportion. All Namban (Portuguese and Spanish) who propagate the doctrine of the Catholics, or bear this scandalous name, shall be imprisoned in the Onra, or common jail of the town. The whole race of the Portuguese with their mothers, nurses and whatever belongs to them, shall be banished to Macao. Whoever presumes to bring a letter from abroad, or to return after he hath been banished, shall die with his family; also whoever presumes to intercede for him, shall be put to death. No nobleman nor any soldier shall be suffered [allowed] to purchase anything from the foreigner.

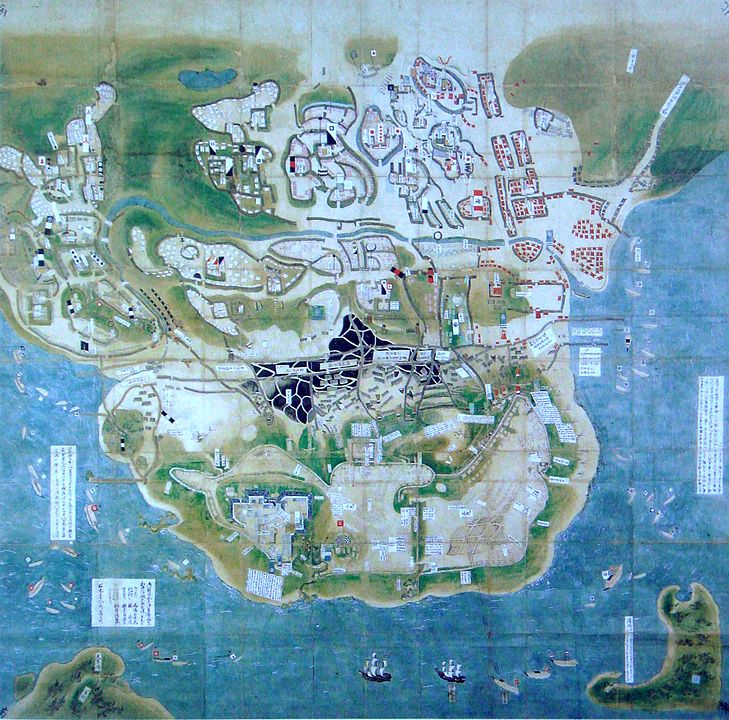

The page notes, however, that the Sakoku regime did allow foreign trade to continue to be conducted through four “gateways”:

The largest was the private Chinese trade at Nagasaki (who also traded with the Ryūkyū Kingdom), where the Dutch East India Company was also permitted to operate… Tashiro Kazui has shown that trade between Japan and these entities was divided into two kinds: Group A in which he places China and the Dutch, “whose relations fell under the direct jurisdiction of the Bakufu at Nagasaki” and Group B, represented by the Korean Kingdom and the Ryūkyū Kingdom, “who dealt with Tsushima (the Sō clan) and Satsuma (the Shimazu clan) domains respectively.”

Also, this:

All contact with the outside world became strictly regulated by the shogunate, or by the domains (Tsushima, Matsumae, and Satsuma) assigned to the task. Dutch traders were permitted to continue commerce in Japan only by agreeing not to engage in missionary activities…

The sakoku policy was also a way of controlling commerce between Japan and other nations, as well as asserting its new place in the East Asian hierarchy. The Tokugawa had set out to create their own small-scale international system where Japan could continue to access the trade in essential commodities such as medicines, and gain access to essential intelligence about happenings in China, while avoiding having to agree to a subordinate status within the Chinese tributary system.

The Dutch, it seems clear, were very happy to engage in trade with the no-proselytizing condition attached– especially if it could get them into markets in which Portugal had previously been strong…

The banner image above is a painting of Dutch and Chinese ships coming to the designated trading spot in Nagasaki Bay, in the Sakoku era.

Hong Taiji establishes the Qing dynasty

We have met Hong Taiji several times before. He was the son of Nurhaci, who had established the Later Jin khanate, one of the remnants of the former Mongol empire in northern China. And like Nurhaci he repeatedly challenged and fought the Ming military, gradually eroding its strength.

In1635, he changed the name of the ethnic group he headed from “Jurchen” to “Manchu”, and in 1636 he changed the name of his dynasty from “Later Jin” or “Great Jin” to “Great Qing”, or just “Qing.”

English-WP tells us this about Hong Taiji in 1636:

In 1636, Hong Taiji invaded Joseon Korea… as the latter did not accept that Hong Taiji had become emperor and refused to assist in operations against the Ming. With the Joseon dynasty surrendered in 1637, Hong Taiji succeeded in making them cut off relations with the Ming dynasty and force them to submit as tributary state of the Qing Empire. Also during this period, Hong Taiji took over Inner Mongolia in three major wars, each of them victorious. From 1636 until 1644, he sent 4 major expeditions into the Amur region. In 1640 he completed the conquest of the Evenks, when he defeated and captured their leader Bombogor. By 1644, the entire region was under his control.

Hong Taji’s plan at first was to make a deal with the Ming dynasty. If the Ming was willing to give support and money that would be beneficial to the Qing’s economy, the Qing in exchange would not only be willing to not attack the borders, but also admit itself as a country one level lower than the Ming dynasty; however… the Ming refused the exchange… Hong Taiji had not wanted to conquer the Ming. The Ming’s refusal ultimately led him to take the offensive. The people who first encouraged him to invade China were his Han Chinese advisors Fan Wencheng, Ma Guozhu, and Ning Wanwo…

England’s King Charles sends EIC rival to Surat

By 1636, the venerable, chartered-in-1600 East India Company (EIC) and King Charles I were both alike facing financial woes and popular opposition. In his 1907 study of the interaction of European powers in India in the 17th century the English historian William Wilson Hunter (WWH) wrote about this about the EIC’s reputation in England in the 1630s (p.173):

Cheap pepper and cloves mattered little to the country gentlemen of England, battling for their liberties with the Crown. To the people at large the Company represented the survival of a royal prerogative, which had grown unpopular even under Elizabeth, become intolerable under James, and was, in 1624, sternly curtailed by statute. A monopoly might be needful for the armed trade which was then the only trade possible in the East. Yet to the rising spirit of the nation, the exclusive privileges granted to the Company by King James seemed scarcely more bearable than those granted by the Borgian Pope to Portugal and Spain. Its sufferings, with the exception of the Amboyna outrage, touched no chord of popular sympathy. Up to 1628, books for or against the Company were published at intervals. But from its appeal to Parliament in 1628 onwards until 1640, I do not find that a single book or pamphlet in its interests issued from the press. Parliament and the nation left the Company severely alone to the king.

Regarding King Charles in this era, English-WP tells us:

there was little financial capacity for Charles to wage wars overseas. Throughout his reign Charles was obliged to rely primarily on volunteer forces for defence and on diplomatic efforts to support his sister, Elizabeth, and his foreign policy objective for the restoration of the Palatinate. England was still the least taxed country in Europe, with no official excise and no regular direct taxation…

In these circumstances, Charles devised several ways of raising revenues. In 1635, he granted to the wealthy British merchant William Courteen a license to trade with the east, “at any location in which the East India Company had no presence.” This of course directly violated the EIC’s charter which had granted it a monopoly on all English trade with “the east.”

WWH wrote this about the matter (p.179-84, passim):

Wealthy merchants were now willing to stake their fortunes on breaking down the Company’s monopoly, and they found gentlemen about the king’s person ready, for a consideration, to gain his Majesty’s ear. The most famous of these cabals of the City and Whitehall was Courten’s Association; it had lasting consequences on the India trade, and it illustrates the hostile combinations to which the Company, as long as it depended on the royal favour, was exposed. The chief actors in the drama were Sir William Courten and Sir Paul Pindar, two London merchants, who between them “lent” the king £200,000; and with them was Endymion Porter, groom of the bedchamber and his Majesty’s factotum for secret affairs…

In 1635 the king granted a license to his three friends on the ground that the Company had consulted only its own interests, neglected those of the nation, and broken the conditions on which its exclusive privileges had been bestowed. Instead, however, of giving the three years’ notice Charles assured the Company that the new association would not trade within its jurisdiction, but was to “be employed on some secret design which his Majesty at present thought not fit to reveal.”

In vain the dismayed governor waited in the Whitehall antechamber all forenoon. He only succeeded in thrusting a petition into the king’s hand as his Majesty passed forth after dinner, but got not a word in reply. News soon arrived that two of Courten’s ships which sailed “without any cargoes” almost as undisguised privateers, had plundered an Indian vessel in the Red Sea; and that the Company’s servants at Surat were in prison for the piracy. Other of Courten’s captains so outraged the Canton magistrates that the English were declared enemies of the Chinese Empire, and were to be forever excluded from its ports.

Assessing the effects of the Courten venture on the EIC’s key Indian HQ at Surat, he wrote (pp.211-15):

In 1636 arrived Captain Weddell of Courten’s Association, with a letter from King Charles to our president, intimating that under his Majesty’s authority six ships “had been sent on a voyage of discovery to the South Seas,” and that “the king himself had a particular interest” in the expedition. Presently came news that two of these ships “to the South Seas” had turned pirates in the Red Sea and plundered an Indian vessel. The Moghul governor at once seized our factory at Surat, threw the president and Council into prison for two months, and only released them on payment of 170,000 rupees, or about £18,000, and on their solemn oath (in spite of their protestations of innocence) never again to molest a Moghul ship.

As in 1623 the Moghul government had held the Company’s servants responsible for the piracy of their public enemies the Dutch, so in 1636 it punished them for the piracy of Courten’s interlopers. “Wee must beare the burthen,” says a sorrowful despatch quoted by Anderson, “and with patience sitt still, until we may find these frowning tymes more auspicious to us and to our affayres.”

A still heavier blow was about to fall on the poor prisoners at Surat. While the piracies of Courten’s Association brought them into disgrace with the Moghul government, the ablest captain of the interlopers, Weddell, resolved to snatch the fruits of the Surat president’s convention with the Portuguese viceroy. He sailed to Goa, and, on the strength of a letter from King Charles, got leave in 1637–1638 to hire a house and to land his goods. After forcing himself, by the same authority, on the Company’s struggling factories from the Bay of Bengal to near the Straits of Malacca, he fixed his headquarters at Rajapur on the Bombay coast. The site was well chosen. It lay up a long tidal creek, in the independent kingdom of Bijapur, about half-way between Goa and the modern city of Bombay. It thus cut in two the Company’s line of communication between Surat and Goa, as the Company’s settlement at Surat had cut in two the Portuguese line of communication between Goa and Diu. The Moghul Empire had not then advanced so far down the coast, and Rajapur formed a chief inlet of the Arabian commerce for the yet unconquered kingdoms of the South. In vain the Company’s servants at Surat protested and tried to found a rival station in the South. Captain Weddell secured by lavish gifts the support of the King of Bijapur, and began to plant factories along the coast. The sagacity of his selection is proved by the part which these factories played in the subsequent annals of the Company.

From home the Surat factory could get no succour, nor any certain sound from their distracted masters, then in their desperate struggle with the court cabal. We have seen that fifty-seven ships and eighteen pinnaces had been sent out for port to port trade alone, during the twelve years ending 1629. The Company’s records, which during the same period abound in journals of voyages to and from India, preserve only eight such documents for the thirteen disastrous years from King Charles’s grant to Courten’s Association in 1635 to his Majesty’s death in 1649.