In 1628 CE, a long-feared Chinese pirate, Zheng Zhilong first of all beat the Ming navy, then decided to become its admiral. In Sweden, a large crowd of citizens, along with most of the foreign ambassadors in Stockholm, watched from shore as King Gustavus Adolphus’s pet power-projection project, a 226-foot warship called Vasa, sank ignominiously into the depths of Stockholm harbor on its (fully-armed) maiden voyage. In England, King Charles I got into some serious fights with parliament. That caused headaches for the East India Company (EIC) but it did not halt the launching of two new colonization projects in the New World, at Nevis and Salem…

Short(-ish) takes on all of this, below.

Zheng Zhilong switches sides

Zheng Zhilong had been born in Fujian in 1604. When he was a teenager, he left home by jumping onto a merchant ship traveling to Macau, where he was baptized by the local (Portuguese) Jesuits. As we know, both the Portuguese and Dutch were active in the waters and trade-routes along China’s east coast, and by 1624, Zheng was working for the Dutch VOC as a privateer, that is, a pirate-for-hire harassing Chinese shipping. He also ran a protection racket to squeeze local fishermen and then joined (or led?) a confederation of pirates called the Shibazhi.

English-WP tells us this:

In 1628, Zheng Zhilong defeated the Ming Dynasty’s fleet. The Ming Dynasty’s southern fleet surrendered to Shibazhi, and Zheng decided to switch from being a pirate captain to working for the Ming Dynasty in an official capacity. Zheng Zhilong was appointed major general in 1628…

After joining the Ming navy, Zheng and his wife resettled on an island off the coast of Fujian, where he operated a large armed pirate fleet of over 800 ships along the coast from Japan to Vietnam. He was appointed by the Chinese Imperial family as “Admiral of the Coastal Seas”. In this capacity he defeated an alliance of Dutch East India Company vessels and junks under renegade Shibazhi pirate Liu Xiang (劉香) on October 22, 1633 in the Battle of Liaoluo Bay. The spoils that followed from this victory made him fabulously wealthy. He bought a large amount of land (as much as 60% of Fujian), and became a powerful landlord.

In those decades of the early-modern era in which sea-power was becoming the paramount marker of a powerful nation, Zheng Zhilong was far from the first admiral who had started out as a pirate. Two earlier examples were the Ottoman admiral known in the west as “Barbarossa” and England’s Francis Drake.

Sweden’s pride and joy capsizes

Gustavus Adolphus had been King of Sweden since 1611 and had done a lot to make Sweden into a great European power. But Sweden was still largely “locked” inside the Baltic, since Denmark controlled Norway and between them they controlled the straits that would allow access from the Baltic to the North Sea. The Baltic was, of course, quite an economic/trading powerhouse in its own right; but still, Gustavus Adolphus and all other savvy European rulers knew that even greater wealth could be made by plying the world’s great oceans. (Heck, he even had as a key advisor the same Hugo Grotius who had been one of the architects of the Dutch VOC and who had smartly escaped from imprisonment in a book-box…)

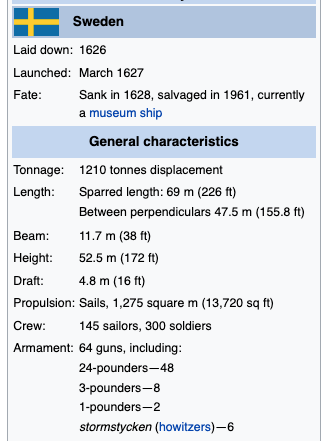

So building a fleet of large fighting ships capable of besting the great ships of the existing European globalists must have seemed like a no-brainer. The first and biggest of these would be the Vasa, named, I believe for the King’s family dynasty. This, from WP:

On 10 August 1628, Captain Söfring Hansson ordered Vasa to depart on her maiden voyage to the naval station at Älvsnabben. The day was calm, and the only wind was a light breeze from the southwest. The ship was warped (hauled by anchor) along the eastern waterfront of the city to the southern side of the harbor, where four sails were set, and the ship made way to the east. The gun ports were open, and the guns were out to fire a salute as the ship left Stockholm.

As Vasa passed under the lee of the bluffs to the south (what is now Södermalm), a gust of wind filled her sails, and she heeled suddenly to port. The sheets were cast off, and the ship slowly righted herself as the gust passed. At Tegelviken, where there is a gap in the bluffs, an even stronger gust again forced the ship onto its port side, this time pushing the open lower gunports under the surface, allowing water to rush in onto the lower gundeck. The water building up on the deck quickly exceeded the ship’s minimal ability to right itself, and water continued to pour in until it ran down into the hold; the ship quickly sank to a depth of 32 m (105 ft) only 120 m (390 ft) from shore. Survivors clung to debris or the upper masts, which were still above the surface. Many nearby boats rushed to their aid, but despite these efforts and the short distance to land, 30 people reportedly perished with the ship. Vasa sank in full view of a crowd of hundreds, if not thousands, of mostly ordinary Stockholmers who had come to see the great ship set sail. The crowd included foreign ambassadors, in effect spies of Gustavus Adolphus’ allies and enemies, who also witnessed the catastrophe.

There was, of course, an enquiry:

“Why did you build the ship so narrow, so badly and without enough bottom that it capsized?” the prosecutor asked the shipwright Jacobsson. Jacobsson stated that he built the ship as directed by Henrik Hybertsson (long since dead and buried), who in turn had followed the specification approved by the king… In the end, no guilty party could be found.

Salvagers were able to haul up the guns, but the ship itself sank further and further into the mud and was not re-discovered until 1961, when it was hauled up almost intact and now sits in a museum. (Part of its salvaged bow is shown in the banner image above.)

As for the King’s dreams of building a global empire to rival the ones the Dutch or English were building, they did not lead to very much: just eight little settlements along the banks of the Delaware River.

Parliamentary trouble brews for England’s Charles

In 1627, England’s King Charles I, still in his twenties, had gotten into a war to support the Huguenots in France– that, though he had also married a daughter of France’s Bourbon (Catholic) king. To finance the war, he tried to impose a “forced loan”, that is, a tax levied without parliamentary consent. Parliament, not surprisingly, opposed that. Then, this:

In November 1627, the test case in the King’s Bench, the “Five Knights’ Case”, found that the king had a prerogative right to imprison without trial those who refused to pay the forced loan. Summoned again in March 1628, on 26 May Parliament adopted a Petition of Right, calling upon the king to acknowledge that he could not levy taxes without Parliament’s consent, not impose martial law on civilians, not imprison them without due process, and not quarter troops in their homes. Charles assented to the petition on 7 June, but by the end of the month he had prorogued Parliament and re-asserted his right to collect customs duties without authorisation from Parliament.

Then, on 23 August, Charles’s favorite, the Duke of Buckingham, who was deeply unpopular with the public, was assassinated:

Charles was deeply distressed. According to Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon, he “threw himself upon his bed, lamenting with much passion and with abundance of tears”. He remained grieving in his room for two days. In contrast, the public rejoiced at Buckingham’s death, which accentuated the gulf between the court and the nation, and between the Crown and the Commons.

The following year, Charles convened a new session of parliament. Members of the House of Commons began to voice opposition to his taxation policies (then known as “tonnage and poundage”.) On March 2, 1629, Charles ordered an adjournment of the new parliament. But the MPs wanted to have their say! They–

held the Speaker, Sir John Finch, down in his chair so that the ending of the session could be delayed long enough for resolutions against Catholicism, Arminianism and tonnage and poundage to be read out and acclaimed by the chamber. The provocation was too much for Charles, who dissolved Parliament and had nine parliamentary leaders, including Sir John Eliot, imprisoned over the matter, thereby turning the men into martyrs, and giving popular cause to their protest.

His problems with Parliament will continue.

As would England’s pursuit of its global raiding and plundering projects in the East Indies and the Americas.

Political rifts in London challenge the EIC

Regarding the English East India Company (EIC), historian William Wilson Hunter noted in his 1907 history of the company’s operations in the 17th century that the rift between King and Parliament, that was widening worryingly in 1628, posed new challenges to the Company. In 1628, he wrote, its fortunes were “at a low ebb.”

The company felt it needed to issue a “Remonstrance” to Parliament that year. The Remonstrance made these argument (WWH, pp.170-72):

So far from weakening the nation, the Company urged that its fleets formed a vast training school for the English marine, a magazine from which the royal navy could draw both men and munitions of war. That so far from decreasing the national wealth, it brought to England a store of Indian products of which only a portion was consumed at home, while the greater part was re-exported to other countries, at a large profit to the realm. Of £208,000 worth of pepper imported in 1627, no less than £180,000 worth was re-exported abroad. It urged that while the Crown thus secured an increase to its customs, the people were enabled to buy spices at much lower rates; although in some articles the Dutch interference had again doubled the prices. That the gentry gained by the increased exportation of wool and woolen stuffs, “which doth improve the landlords’ rents.” That the Company was in fact become a defence of the commonwealth, “to counterpoise the Hollanders’ swelling greatness by trade, and to keep them from being absolute Lords of the Seas.” It had also deprived Spain of the “incredible advantage of adding the traffique of the East Indies to the treasure of the West.” That if the English trade with the Indies should fail, then other English commerce would fail with it, and pass into the hands of the Dutch…

The Company declared that the export of bullion to buy Indian wares, which it resold to foreign nations at a great profit, was a good employment for the national treasure. It declared that, since England had neither gold nor silver, she could acquire bullion only “by making our commodities which are exported, to overbalance in value the foreign wares which we consume.” “It is not … the keeping of our money in the kingdom which makes a quick and ample trade, but the necessity and use of our wares in foreign countries, and our want of their commodities which causeth the vent and consumption on all sides.”

WWH was a strong admirer of the record of the EIC. He recognized that the growing rift between Parliament and King had put the Company into a hard position (p.173):

To the people at large the Company represented the survival of a royal prerogative, which had grown unpopular even under Elizabeth, become intolerable under James, and was, in 1624, sternly curtailed by statute. A monopoly might be needful for the armed trade which was then the only trade possible in the East. Yet to the rising spirit of the nation, the exclusive privileges granted to the Company by King James seemed scarcely more bearable than those granted by the Borgian Pope to Portugal and Spain. Its sufferings, with the exception of the Amboyna outrage, touched no chord of popular sympathy. Up to 1628, books for or against the Company were published at intervals. But from its appeal to Parliament in 1628 onwards until 1640, I do not find that a single book or pamphlet in its interests issued from the press. Parliament and the nation left the Company severely alone to the king.

There was also the still-controversial matter of the EIC having failed to protect its representatives in the East Indies from the torture and wanton cruelty of the Dutch at Amboyna, in 1623. The last thing the English authorities had done to try to secure redress from the Dutch for the men’s murders had been to capture and hold a number of Dutch merchant ships in the English Channel.

WWH wrote (p.175) that the EIC’s directors knew that their Remonstrance to Parliament had angered the King. But Charles,

assured them in July, 1628, that such was his love to commerce in general and to the Company in particular that he would not have them doubt of his protection, and meanwhile he would feel obliged for a loan of £10,000. As the loan was not forthcoming, he transferred his civilities to the Dutch. In the following month he was said to have taken their bribe of £30,000, and he certainly let their ships go.

English colonizers in Nevis, Salem

In 1626, the English colonists on the small island of St. Kitts had joined with French colonists to commit a broad genocide of the indigenous Kalinago people there. In 1628, an English colonist from St. Kitts called Anthony Hilton moved with 80 other settlers to the nearby island of Nevis, “soon to be boosted by a further 100 settlers from London… Hilton became the first Governor of Nevis.” England’s King James I had “asserted sovereignty over” Nevis in 1620.

WP tells us that the island had been named “Oulalie” (Land of Beautiful Waters”) by its pre-European indigenes. Also,that it, “had been settled for more than two thousand years by Amerindian people prior to having been sighted by Columbus in 1493. The indigenous people of Nevis during these periods belonged to the Leeward Island Amerindian groups popularly referred to as Arawaks and Caribs, a complex mosaic of ethnic groups with similar culture and language.”

Within just a couple of decades of 1628, Nevis would become, “a dominant source of wealth for Great Britain and the slave-owning British plantocracy.” The fate of its Arawak and Carib people can barely be imagined.

Meanwhile, further to the north…

In 1620, as we know, the first Puritan settlers had come to settle in the “Plymouth” colony in the southeast of today’s Massachusetts. Now, in 1628, another group of English Puritan settlers led by a John Endecott, traveled to establish a second colony a little further north and west, which they named Salem.

English-WP tells us that Endecott was “a zealous and somewhat hotheaded Puritan.” Also, this:

In March 1627/8 Endecott was one of seven signatories to a land grant given to “The New England Company for a Plantation in Massachusetts” (or the New England Company) by the Earl of Warwick on behalf of the Plymouth Council for New England…

Endecott was chosen to lead the first expedition, and sailed for the New World aboard the Abigail with fifty or so “planters and servants” on 20 June 1628… [He] was not formally named governor of the new colony until it was issued a royal charter in 1629. At that time, he was appointed governor by the Company’s council in London, and Matthew Craddock was named the Company’s governor in London.

Endecott’s responsibility was to establish the colony and to prepare it for the arrival of additional settlers. The winters of 1629 and 1630 were difficult compared to those in England, and he called on the Plymouth Colony for medical assistance. His wife, who had been ill on the voyage over, died that winter. Other difficulties he encountered included early signs of religious friction among the colony’s settlers (dividing between Nonconformists and Separatists), and poor relations with Thomas Morton, whose failed Wessagusset Colony and libertine practices (which included a maypole and dancing) were anathema to the conservative Puritanism practiced by most settlers in the Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies. Early in his term as governor he visited the abandoned site of Morton’s colony and had the maypole taken down. When one group of early settlers wanted to establish a church independent of that established by the colonial leadership, he had their leaders summarily sent back to England.

Endecott’s first tenure as governor came to an end in 1630, with the arrival of John Winthrop and the colonial charter.