Lower down in today’s bulletin I’ll provide a quick overview of how, in 1624 CE, the four big European colonialisms– in chronological order, Portugal, Spain, England, and Netherlands– were roiling the world and what was happening in France that showed it to be on the brink of a big eruption of the same maladie de grandeur.

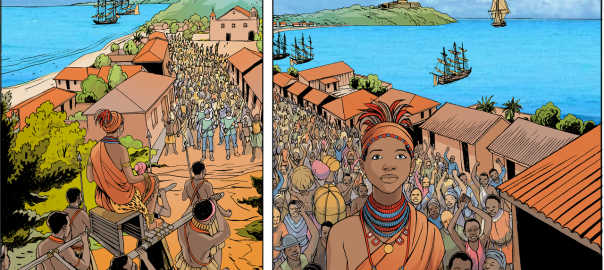

But first, here’s a shoutout to Queen Nzingha Mbande (1583–1663), who in 1624 became Queen of the Ambundu Kingdom of Ndongo, located in present-day northern Angola. (She is represented in a UNESCO publication, in the banner image above.)

English-WP says about Queen Nzingha that she was, “Born into the ruling family of Ndongo, [she] received military and political training as a child, and she demonstrated an aptitude for defusing political crises as an ambassador to the Portuguese Empire.”

It cites the historian and activist Aurora Levins Morales as having written about Nzingha that,

She was a fierce anticolonial warrior, a militant fighter, a woman holding power in a male-dominated society, and she laid the basis for successful Angolan resistance to Portuguese colonialism all the way into the twentieth century… [But] she was also an elite woman living off the labor of others, murdered her brother and his children, fought other African people on behalf of the Portuguese, and collaborated in the slave trade.

We all definitely need to learn more about the wrenching ethical dilemmas that Western colonialisms/imperialisms have for hundreds of years now forced onto their non-Western victims…

And now, my Headlines in Colonialism for 1624. I’ll look at East Asia first, then the Americas, then circle back to what was happening in France.

Chinese force VOC out of Penghu

In February 1624, a Chinese admiral called Yu Zigao took command of Zhejiang and Fujian’s military forces. He then immediately, “took a hard line against the Dutch East India Company stronghold on Penghu Island in the Pescadores. They had previously agreed to withdraw to Taiwan but had continued to delay the move.” The Pescadores are a group of small islands between Taiwan and mainland China.

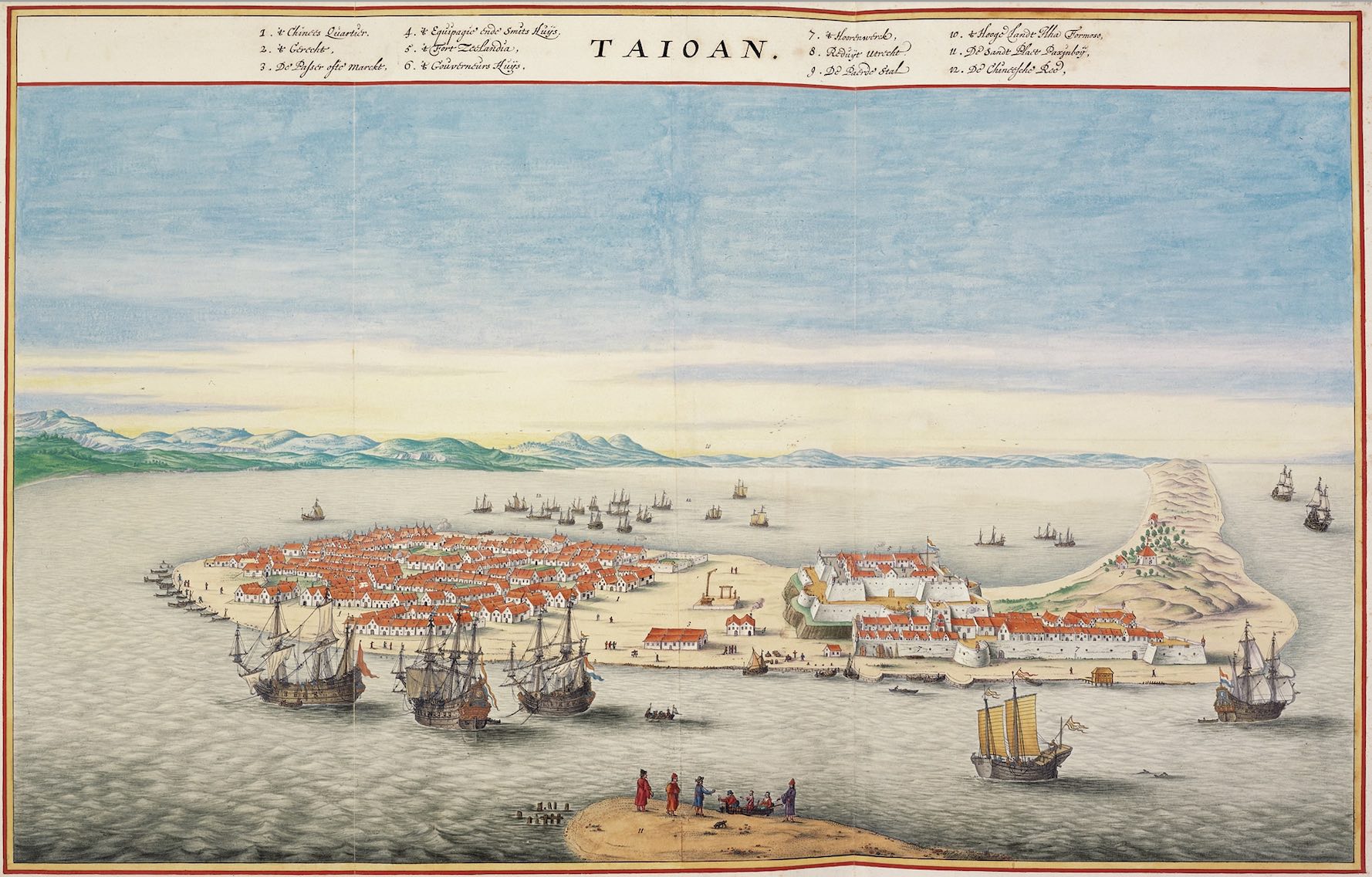

Yu had earlier been one of the first Chinese officials to procure several Hongyipao (“red-barbarian”) cannons. In August, he assembled his provincial forces and forced the Dutch– that is, the original “red-haired barbarians” to dismantle their fortifications. They then removed themselves to Taiwan, where on a precarious sand-spit they established Fort Zeelandia (at right).

Tokugawa shōgun forces Spanish out of Japan

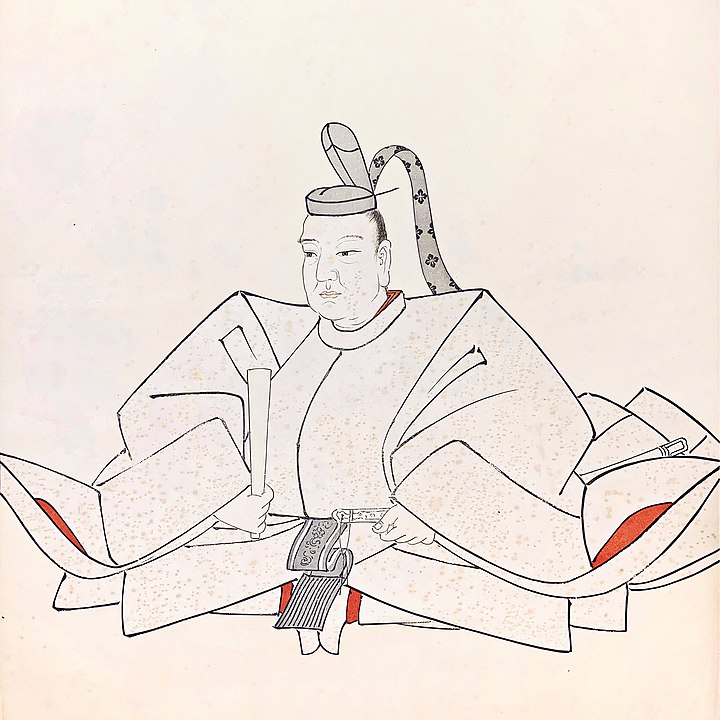

In 1623, Japan had acquired a new shōgun, Tokugawa Iemitsu, who was the 19-year-old son of shōgun Tokugawa Hidetada. Hidetada had retired and stayed on in the new role of Ōgosho– retired shōgun. One of the early acts of the reconfigured shogunate was to order all the Spanish armed traders and missionaries who were still in the country to leave, and to close down trade with the Spanish-controlled Philippines.

It is not clear how effectively or speedily this order was implemented. But Japan was well on its way to Iemitsu’s enactment of the formal Sakoku (“closed country”) laws, which nine years later would take the country into a 214-year period of very limited interaction with the rest of the world.

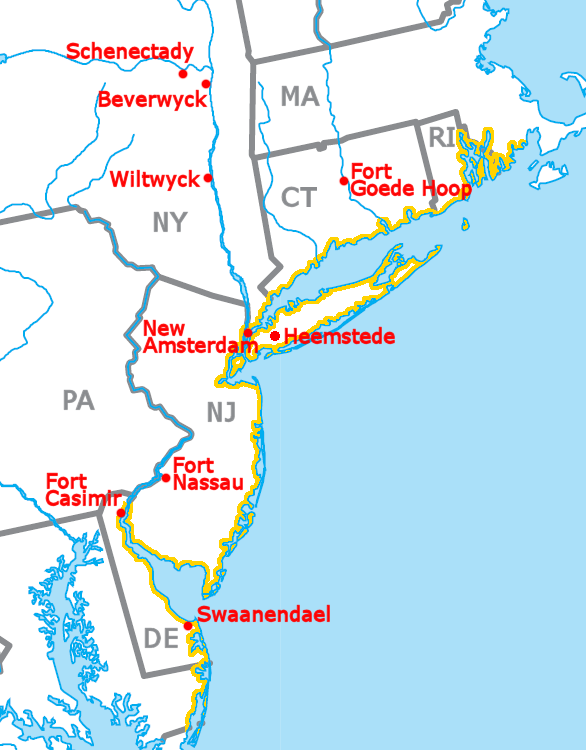

Netherlands takes new steps in N. American settlement project

In 1621, the Dutch parliament had awarded the emerging Dutch nation’s “patent” for colonial exploitation of all of the Americas to the new “Dutch West India Company” (GWC). The group of GWC settlements in mid-Atlantic North America, which stretched from today’s state of Delaware to Connecticut, was called “New Netherland.” In 1624, the Dutch parliament designated New Netherland as an additional province of the Dutch Republic itself– a formal act of annexation. It also lowered the northern border of its North American dominion to 42 degrees latitude “in acknowledgment of the claim by the English north of Cape Cod,” which it apparently recognized as having some validity. (In other words, the Dutch did not feel as confident in confronting the English in N. America as they had, just the previous year, over in the East Indies… )

English-WP tells us:

The Dutch named the three main rivers of the province the Zuyd Rivier (South River; the Delaware), the Noort Rivier (North River; the Hudson), and the Versche Rivier (Fresh River; the Connecticut). Discovery, charting, and permanent settlement were needed to maintain a territorial claim. To this end in May 1624, the [GWC] landed 30 families at Fort Orange and Noten Eylant (today’s Governors Island) at the mouth of the North River.

This colony (province) continued to grow slowly over the decades that followed. The main economic activity was procurement of furs from the many Native people who lived in the area.

England’s King James bails out the Virginia Company

In 1622, as we know, the Powhatan chief Opechancanough had led a well-coordinated series of surprise attacks on English settlements along both sides of a 50-mile (80 km) long stretch of the James River, in Virginia that killed 347 settlers and abducted many others. (What I had not known before is that in 1623, two Jamestown settlers pretended to conclude a truce with the Powhatan, and during the meeting to seal the truce they proposed a toast using liquor laced with poison: “200 Virginia Indians were killed or made ill by the poison and 50 more were slaughtered by the colonists. For over a decade, the English settlers killed Powhatan men and women, captured children and systematically razed villages, seizing or destroying crops.” It is deeply unsurprising to learn this now.)

But long story short, clearly the Virginia Company’s colonization project was not going as well as its many private investors in London had hoped. So in 1624, King James “nationalized” the project by designating Virginia as a “Crown Colony.”

By the way, in 1624 “Virginia” still denoted a much larger land area than the state of Virginia does today. Later, the English Crown would split off portions of it into “Maryland” and the “Carolinas”.

In Brazil, Dutch seize Bahia from Portuguese

Here’s a last snippet of colonial news before we go to France…

In December 1623, a large Dutch fleet of 35 ships, carrying 6,500 men, left Netherlands en route to the mid-Atlantic Cape Verde Islands. 13 of the ships were owned by the Dutch government; the rest by the VOC– the Dutch East India Company. Their goal was the capture of the city of Salvador da Bahia, on the eastern coast of Brazil– which they planned to establish as a staging-post for VOC ships sailing on the very profitable routes between Netherlands and the East Indies. (Not as crazy as it sounds, given the wind and tide patterns.) In addition they hoped to control the sugar-cane plantations that had been sprouting up all around Bahia.

They succeeded.

However, just to finish this little story, the following year a large force from the joint Spanish-Portuguese navy consisting of 43 large ships and 12,000 men set out from Cadiz and effected the successful Reconquista of Bahia from the Dutch. This page on WP tells us that the forces of the Reconquista captured, “1,912 Dutch, English, French, and German soldiers surrendered, and 18 flags, 260 guns, 6 ships, 500 black slaves, and considerable amount of gunpowder, money, and merchandise.”

Also, this: “The Dutch did not return to Brazil until 1630, when they conquered Pernambuco from the Portuguese.”

Cardinal Richelieu sets the stage for France’s colonial eruption

In August 1624, France’s Bourbon king, Louis XIII, appointed Cardinal Richelieu as his First Minister of State. He had been Foreign Secretary since 1616, and had had to steer France through the complex shoals of the many rivalries that plagued continental Europe, including Louis’s own rivalry with the fellow-Catholic Habsburgs in Spain and elsewhere; the rivalry with the militant Protestants of the Netherlands; and of course central Europe’s ongoing and very bloody “Thirty Years War”, which started in 1618.

During his time in office, Richelieu did a lot to centralize the French state, primarily by curtailing the power of the nobles. (He also helped standardize the French language by founding the Académie Francaise.)

English-WP also says this about Richelieu:

When Richelieu came to power, New France, where the French had a foothold [in North America] since Jacques Cartier, had no more than 100 permanent European inhabitants. Richelieu encouraged Louis XIII to colonize the Americas by the foundation of the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France in imitation of the Dutch West India Company. Unlike the other colonial powers, France encouraged a peaceful coexistence in New France between Natives and Colonists and sought the integration of Indians into colonial society. Samuel de Champlain, governor of New France at the time of Richelieu, saw intermarriage between French and Indians as a solution to increase population in its colony. Under the guidance of Richelieu, Louis XIII issued the Ordonnance of 1627 by which the Indians, converted to Catholicism, were considered as “natural Frenchmen… and as such may come to live in France when they want, and acquire, donate, and succeed and accept donations and legacies, just as true French subjects, without being required to take letters of declaration of naturalization.”

However, the French were very slow in getting this N. American colonization project off the ground. In 1666, some 20 years after Richelieu’s death, there was a census of “New France” that counted a population of only 3,215 French persons there.