1622 CE was a huge year in geopolitics. A lot of what happened this year had to do with the very long-drawn-out deterioration of the Portuguese empire’s position on the fringes of the Indian Ocean.

I’ll try to keep each entry here brief. Here’s the main Table of Contents. Scroll on down to what interests you:

Two main stories:

- Powhatans try to expel English invaders at Jamestown

- The Dutch VOC tries but fails to seize Portuguese fort at Macau

Two side stories:

- An indigenous uprising against the Portuguese in Kongo

- Anglo-Persian force takes Hormuz from Portugal

Two significant incidents:

- Strangling of young Ottoman Sultan Osman II

- Hurricane sinks Spanish treasure fleet off Florida

Let’s go!

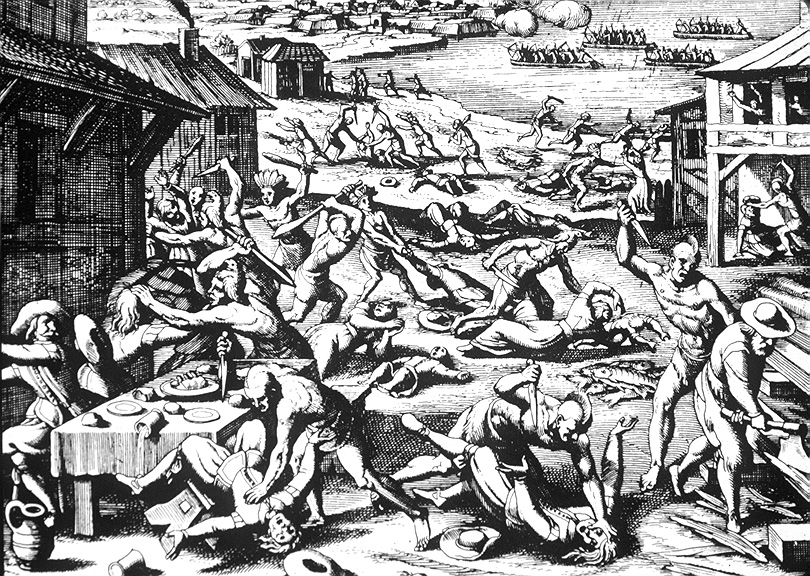

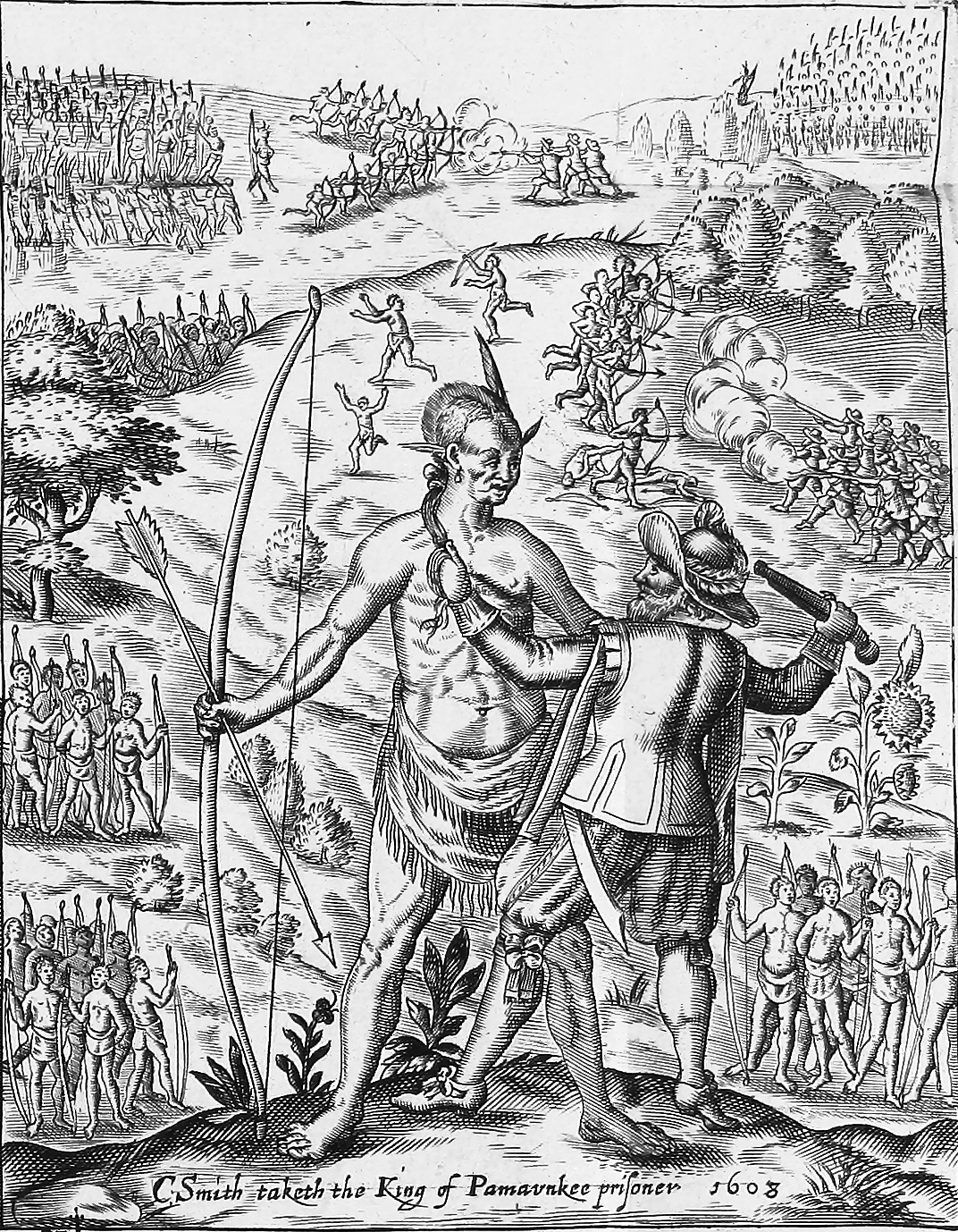

Powhatans try to expel English invaders at Jamestown

This is from the English-WP account of what happened at the colonial settlement on the “James River” that was also sycophantically named for the English monarch: “At first, the natives were glad to trade provisions to the colonists for metal tools, but… [t]he Powhatan peoples had soon realized that the Englishmen did not settle in Jamestown to trade with them. The English wanted more; they wanted control over the land.”

Indeed they did. By 1622 they had started plantations to grow tobacco for export, using enslaved Africans and indentured Europeans to work the hard red soil of the area.

In 1618, the eponymous Chief Powhatan had died. His brother Opitchapam became the nominal head of the confederacy; then in 1620 or 1621 a feistier younger brother, Opchanacanough, succeeded him. Opchanacanough and a friend, war-chief, and advisor called Nemattanew began to develop plans for a war to defend their native land:

they planned to shock the English with an attack that would leave them contained in a small trading outpost, rather than expanding throughout the area with new plantations. In the spring of 1622, after a settler murdered… Nemattanew, Opchanacanough launched a campaign of surprise attacks on at least 31 separate English settlements and plantations, mostly along the James River, extending as far as Henricus.

An Indian youth living in the home of a settler living across the river from the colony’s capital, Jamestown, got wind of Opechancanough’s plan and ratted on him to his employer, who rowed across the river to warn the settlement leaders there. They were able to organize some defenses for the capital, but outlying settlements got hammered. The attack was launched on March 22.

During the one-day surprise attack, the Powhatan tribes attacked many of the smaller communities, including Henricus and its fledgling college for children of natives and settlers alike. In the neighborhood of Martin’s Hundred, 73 people were killed. More than half the population died in Wolstenholme Towne, where only two houses and a part of a church were left standing. In all, the Powhatan killed about four hundred colonists (a third of the white population) and took 20 women captive. The captives lived and worked as Powhatan Indians until they died or were ransomed. The settlers abandoned the Falling Creek Ironworks, Henricus, and Smith’s Hundred….

Opechancanough withdrew his warriors, believing that the English would behave as Native Americans would when defeated: pack up and leave, or learn their lesson and respect the power of the Powhatan. Following the event, Opechancanough told the Patawomeck, who were not part of the Confederacy and had remained neutral, that he expected “before the end of two Moones there should not be an Englishman in all their Countries.” He misunderstood the English colonists and their backers overseas.

I’ll say! The revenge of the English was pitiless. They

took revenge against the Powhatan by “the use of force, surprise attacks, famine resulting from the burning of their corn, destroying their boats, canoes, and houses, breaking their fishing weirs and assaulting them in their hunting expedition, pursuing them with horses and using bloodhounds to find them and mastiffs to seaze them, driving them to flee within reach of their enemies among other tribes, and ‘assimilating and abetting their enemies against them”.

In 1624, Virginia was made a “royal colony”. That meant that the Crown took direct authority rather than leaving it to the investors and buccaneers of the privately funded “Virginia Company”. Expansion of the settlements continued. The next Anglo-Powhatan War would erupt in 1644.

The Dutch VOC tries but fails to seize Portuguese fort at Macau

Portugal’s royal-backed armed traders/colonizers had had an agreement with China’s Ming-dynasty rulers since 1557 that allowed them to have a trading post on the country’s Macau Peninsula– and guess what, that trading post had become increasingly fortified in the 60-plus years since then. From there, the Portuguese were able not just to send the fine products of China’s many very advanced manufactories back along the long sea route to Europe but also, very profitably, to handle much of China’s trade with Japan, since the Ming dynasts did not allow direct trading with Japan.

And as we know, since 1580 Portugal had been in a union with Spain, and since 1602 the Dutch had had a feisty armed-trading company, the VOC, that had already made lots of inroads into the trading networks that Portugal had long had in the Spice Islands, to the south of China…

Now, in 1622, the VOC’s governor general, Jan Pieterszoon Coen, decided to tackle the Portuguese in Macau. It did not go well. As English-WP says:

At Batavia, headquarters of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), Coen organized an initial fleet of eight ships for the expedition to Macau, with orders that any Dutch vessel encountered along the way was to be incorporated into the invasion fleet. The soldiers that composed the landing force were specifically selected…

Coen was so satisfied with the fleet that when he wrote to the VOC directors at The Hague he expressed regret for not being able to lead “so magnificent an expedition” in person. The VOC directors did not share Coen’s enthusiasm in this venture, stating that they had enough wars at the time, and ordered Coen to wait until they could make a more informed decision. But the fleet, under the command of Cornelis Reijersen, had already left Batavia on 10 April 1622 before the order was sent.

The ultimate goal of the expedition was to establish a Dutch base of operations on the China coast and force the Chinese to trade with the Dutch, so Reijersen was given the option not to attack Macau; he was to form fortifications on the Pescadores [an archipelago of 90 islands and islets in the Taiwan Strait; aka the Penghu] regardless of whether he attacked Macau.

Anyway, the Dutch fleet picked up some additional ships along the way. (Interestingly, Coen’s orders stated that if Riejersen should meet English ships along the way, he could invite them to join the naval battle but tell them they could not join the planned landing operation or share in the spoils. Understandably, the English captains declined the invitation.)

The battle happened in late June. From the Dutch point of view it was a debacle. The Portuguese had around 150 of their own fighters in the fortress with “an unknown number of black slaves”, who were also ordered to fight. (I’m not sure who the “black” slaves were– possible Africans but more likely people enslaved from various East Indies islands during Portugal’s long control of many of those island chains.)The Dutch had 800 fighters on 13 ships, four of which were sunk in the fighting. The Dutch side suffered more than 300 killed, of whom 136 were actually Dutch. On the Portuguese side, six Portuguese and “a small number” of black slaves were killed.

WP tells us:

The battle was the most decisive defeat ever dealt by the Portuguese to the Dutch in the Far East… Casualties among Dutch officers were especially serious, as seven captains, four lieutenants, and seven ensigns were lost in the battle. In addition to the loss of personnel, the Dutch also lost all their cannons, flags, and equipment. In comparison, the deaths on the Portuguese side numbered only four Portuguese, two Spaniards, and a few slaves; about twenty were wounded. At Batavia, Jan Pieterszoon Coen was extremely bitter about the outcome of the battle, writing “in this shameful manner we lost most of our best men in this fleet together with most of the weapons.”

… Later in 1622, when the Dutch fleet arrived in the Pescadores, the place that Coen believed to be better than Macau from a strategic viewpoint, Admiral Reijersen built a fort there and carried out Coen’s orders to indiscriminately attack Chinese ships, to coerce the Chinese authorities into allowing trade. It was hoped that if this harassment campaign succeeded, the Pescadores might supplant Macau and Manila as a silk entrepôt for the Japan market.

However, the Chinese started to regard the Hollanders as pirates and murderers because of these raids and the attack on Macau, and refused to trade with them. The Chinese then waged war against the Dutch and defeated them during the Sino–Dutch conflicts from 1623–1624, forcing the Dutch to abandon the Pescadores in 1624 for Taiwan.

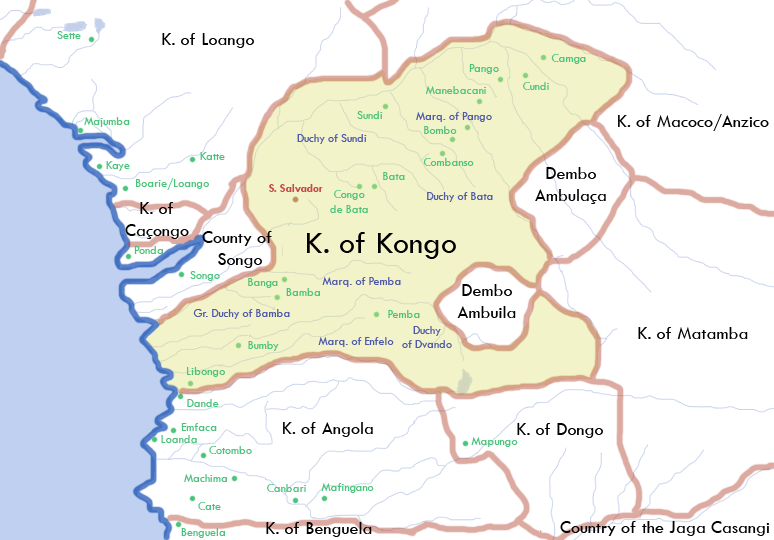

An indigenous uprising against the Portuguese in Kongo

The Portuguese, you may recall, had been in the West African Kingdom of Kongo (not wholly co-terminous with today’s DRC) since the 1480s, and had even converted the King of Kongo to Christianity in 1485. Since then, they had built a series of outposts in the coastal parts of the kingdom from where they continued to try to manipulate the local populations by siding with one against the other, etcetera– while also reaping a constant and profitable “harvest” of enslaved people whom they would either enslave themselves or buy/seize from one of the indigenous groups who had taken captives from their enemies. Many of the enslaved people taken to work on the plantations Portugal had established on São Tomé island from 1493 on had been shipped over from Kongo.

To be honest, the story of the fighting that engulfed much of both Kongo and the neighboring “Kingdom of Angola” in 1622, seems very unclear. But here are some highlights from English-WP. (Be aware that many of the indigenous leaders had adopted Portuguese names by this time):

The First Kongo-Portuguese War began in 1622, initially because of a Portuguese campaign against the Kasanze Kingdom, which was conducted ruthlessly. From there, the army moved to Nambu a Ngongo, whose ruler, Pedro Afonso, was held to be sheltering runaway slaves as well. Although Pedro Afonso, facing an overwhelming army of over 20,000, agreed to return some runaways, the [Portuguese-led] army attacked his country and killed him.

Following its success in Nambu a Ngongo, the Portuguese army advanced into Mbamba in November. The Portuguese forces scored a victory at the Battle of Mbumbi. There they faced a quickly gathered local force led by the new Duke of Mbamba, and reinforced by forces from Mpemba led by its marquis. Both the Duke of Mbamba and the Marquis of Mpemba were killed in the battle. According to Esikongo accounts, they were eaten by the Imbangala allies of the Portuguese.

The Imbangala were apparently “17th-century groups of Angolan warriors and marauders who founded the Kasanje Kingdom.” Their customs sound pretty cruel. They were close allies of the Poruguese and perhaps had even been established/organized by them.

Then this:

Pedro II, the newly crowned king of Kongo, brought the main army, including troops from Soyo, down into Mbamba and decisively defeated the Portuguese, driving them from the country [not clear which country– probably not the whole of Kongo] at a battle waged somewhere near Mbanda Kasi in January 1623. Portuguese residents of Kongo, frightened by the consequences for their business of the invasion, wrote a hostile letter to [their military chief] Correia de Sousa, denouncing his invasion.

Following the defeat of the Portuguese at Mbandi Kasi, Pedro II declared Angola an official enemy. The king then wrote letters denouncing Correia de Sousa to the King of Spain and the Pope. Meanwhile, anti-Portuguese riots broke out all over the kingdom and threatened its long-established merchant community. Portuguese throughout the country were humiliatingly disarmed and even forced to give up their clothes. [!] Pedro, anxious not to alienate the Portuguese merchant community, and aware that they had generally remained loyal during the war, did as much as he could to preserve their lives and property, leading some of his detractors to call him “king of Portuguese”.

As a result of Kongo’s victory, the Portuguese merchant community of Luanda revolted against the governor, hoping to preserve their ties with the king. Backed by the Jesuits, who had also just recommenced their mission there, they forced João Correia de Sousa to resign and flee the country. The interim government that followed the departure was led by the bishop of Angola. They were very conciliatory to Kongo and agreed to return over a thousand of the slaves captured by Correia de Sousa, especially the lesser nobles captured at the Battle of Mbumbi.

Anglo-Persian force takes Hormuz from Portugal

Well, here’s another Portuguese fort on the coast of a body of water connected to the Indian Ocean. This one, at Hormuz (aka Ormuz), had been established by duke Afonso de Albuquerque on Hormuz Island in 1507 as part of a string of Portuguese forts around the always-strategic Straits of Hormuz.

In 1622, the English were in the midst of their campaign to crush and replace Portugal’s privileged strategic position in the Arabian Sea/Gulf of Oman– and the Safavid Shah of Persia, Abbas I, was also eager to oust the Portuguese. (This was the same guy who had had a long relationship with the English Shirley brothers, one of whom had reorganized his army and the other had co-led a diplomatic mission on his behalf to Europe. But recall that at the time of that mission, 1599, the Persian diplomatic group had had to travel to Europe buy a complicated northern route including Russia, in order to get around both the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean and the Portuguese Empire in the Indian Ocean– though its surviving members were able, a couple years later, to return to Persia via the Portuguese-controlled sea-route.)

Shah Abbas had gotten to the point where he wanted to oust the Portuguese from his coastline. But he had no naval power to speak of. So in 1621 or so, one of his commanders (actually, the son of his chief consigliere Allahverdi Khan,

negotiated with the English to obtain their support, promising the English that they would grant them access to the Persian silk trade. An agreement was signed, providing for the sharing of spoils and customs dues at Hormuz, the repatriations of prisoners according to their faith, and the payment by the Persians of half of the supply costs for the fleet.

The English fleet first went to Kishm, some 24 kilometres (15 mi) away, to bombard a Portuguese position there. The Portuguese present quickly surrendered, and the English casualties were few, but included the famous explorer William Baffin [“discoverer” of the eponymous Baffin Bay in northern Canada.]

The Anglo-Persian fleet then sailed to Ormuz and the Persians disembarked to capture the town. The English bombarded the castle and sank the Portuguese fleet present, and Ormuz was finally captured on 22 April 1622. The Portuguese were forced to retreat to another base at Maskat..

The capture of Ormuz gave the opportunity for the [East India] Company to develop trade with Persia, attempting to trade English cloth and other commodities for silk, which did not become very profitable due to the lack of Persian interest and small quantity of English goods.

Two footnotes here: (1) European colonizers often faced this latter issue when they tried to build trade relations with the far more developed manufacturing economies of Asia– basically, that the Europeans produced nothing, except sometimes weapons, that the Asian rulers and their subjects particularly wanted– whereas Europeans loved the fine goods that the factories of India, China, Persia, and the Spice Islands produced. (2) In 1622, Portugal was part of Spain and thus technically at peace with England. After the Spanish learned of the Anglo-Persian capture of Hormuz, they complained mightily. King James held them off– but demanded 10 percent of the profits from the operation as his pay-off for doing so.

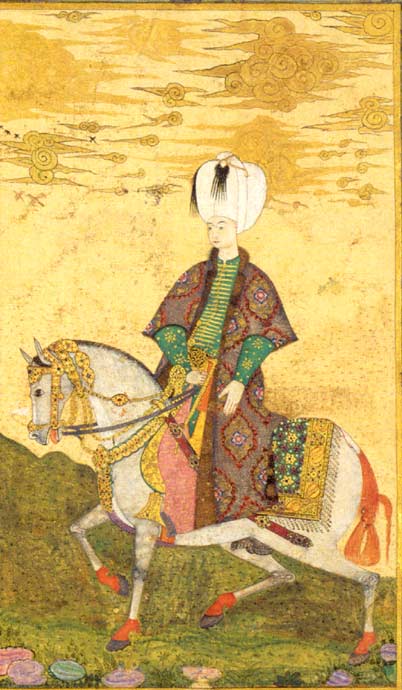

Strangling of young Ottoman Sultan Osman II

Remember how, in 1618, the mother of the possibly unhinged Ottoman sultan Mustafa I had persuaded him to give up the throne to his 14-year-old nephew Osman II?

Osman did not do well. He personally led an Ottoman invasion of Poland which did not go well at all– and then afterwards he tried to place the blame on the Janissaries, who were the empire’s semi-permanent, slave-based military establishment.

They were not happy. They staged an uprising, during which

they imprisoned the young sultan in Yedikule Fortress in Istanbul, where Osman II was strangled to death. After Osman’s death, his ear was cut off and represented to Halime Sultan [Mustafa’s still-powerful mother] and Sultan Mustafa I to confirm his death and that Mustafa would no longer need to fear his nephew. It was the first time in the Ottoman history that a Sultan was executed by the Janissaries.

Guess who got to come back onto the throne? Yes, Mustafa. His restoration to the throne lasted less than a year…

Hurricane sinks Spanish treasure fleet off Florida

Once or twice a year for around a century now, the Viceroyalty of “New Spain” (the lands controlled by Spain in the Americas) would organize a massive fleet of ships to haul off to Spain the treasures mined, produced, or stolen in the Spanish Crown’s truly settler-colonial project in the Americas– and also, those shipped across to Panama from the Philippine Islands. These Treasure Fleets were always sorely needed by the Spanish kings, to fund the wars they continued to wage across Europe and to shore up the Crown’s ever-shaky finances in general. They had also, famously, been targeted by English and other pirates for many decades now, so they would sail in a tight defensive formation.

In September 1622, a 28-ship Treasure Fleet gathered at Havana, but various incidents along the way had delayed their gathering and their setting sail for several weeks beyond the normal set-sail window. A large, well-loaded galleon called Nuestra Señora de Atocha was sailing as rearguard. Like all the ships in the fleet, it was heavily armed with sizeable cannons. English-WP tells us that:

Each ship in the convoy carried crew, soldiers, passengers, provisions, and treasures from all over South America. The Atocha alone carried cargo whose estimates range between $250 and $500 million, including silver from Peru and Mexico, gold and emeralds from Colombia, and pearls from Venezuela, as well as more common goods including worked silverware, tobacco, and bronze cannons.

In the second day of its voyage from Havana, the convoy was overtaken by a hurricane in the Florida Straights. By the morning of 6 September, eight of the ships had sunk and their remains lay scattered from Marquesas Key to the Dry Tortugas. The Nuestra Señora de Atocha had lost all of her 265 crew and passengers except for three sailors and two slaves, who survived by clinging to the mizzenmast… All of her treasure sank with the ship, approximately 30 leagues (140 km) from Havana.

One of the ships that had sunk near the Atocha was the Santa Margarita, which had sunk in approximately 55 feet of water. The Spanish were able to locate some of the Margarita‘s remnants. They

undertook salvage operations for several years with the use of Indian slaves, and recovered nearly half of the registered part of its cargo from the holds of Santa Margarita. The principal method used for the recovery of this cargo was a large brass diving bell with a glass window on one side: a slave would ride to the bottom, recover an item, and return to the surface by being hauled up by the men on deck. It was often lethal, but more or less effective. Dead slaves were recorded as a business expense by the captains of salvage ships… The Spanish worked diligently and were able to salvage most of the Santa Margarita over the next ten years. However, in 60 years of searching, the Spanish never located the Atocha.

The Atocha was not discovered until an American commercial treasure-hunting company called Treasure Salvors found it in 1973. The State of Florida claimed title to the wreck, but in 1982 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the company.

In June 2011, divers from… Treasure Salvors found an antique emerald ring believed to be from the wreck. It is said that the ring is worth an estimated $500,000. The ring was found 56 kilometres (35 mi) from Key West, along with two silver spoons and other artifacts. In 2014, Nuestra Señora de Atocha was added to the Guinness Book of World Records for being the most valuable shipwreck to be recovered, as it was carrying roughly 40 tonnes of gold and silver, and 32 kilograms (71 lb) of emeralds.

The banner image above is a photo of some of the Atocha treasure, from the website of Mel Fisher’s Treasure Salvors.