Another busy year, 1605 CE. Here’s the Table of Contents:

- Guy Fawkes’ plot nearly topples King James; English repression of Ireland continues

- Mughal Empire’s Akbar dies, leaves big political legacy

- Cardinals come to blows when choosing 2nd new pope this year

- Upheaval in Moscow; Polish nobles mount a coup

- Spain plants yet more colonial settlements in “New Spain”

Guy Fawkes’ plot nearly topples King James; English repression of Ireland continues

So we’d left England’s new King James I last year having made the controversial peace with Spain that had aroused so much ire from the generally anti-Catholic stalwarts of the anti-Spanish, pro-Dutch portion England’s political elite. But this, year 1605, it turned out that the Catholics in England, who counted several fairly powerful lords and earls and such among their number, still felt extremely threatened by James… and indeed, throughout 1605 they carefully hatched a big plot against him.

Let’s back up just a little and recall that James was the son of the very Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots, who had been executed by Queen Elizabeth in 1857; but he had been ripped from her arms when still but a babe and had been raised, mainly in Scotland, by Elizabeth-chosen courtiers who brought him up as a Church of England Protestant. But several of the Protestant gentry didn’t wholly trust him– and neither, it turns out, did many Catholics.

Freedom of religion for themselves and their co-believers in Ireland was a definitely an issue for the remaining English Catholics. In Ireland, just about all the resistance to England’s colonizing projects had been led by staunch Irish Catholics (with some help from Spain.) But their rebellion had been crushed in 1601. Now, in March 1605, a proclamation from King James declared that all the people of Ireland were direct subjects of the English/British Crown and owed no allegiance to any local lord or chief. And in July 1605, a follow-on proclamation commanded all Catholic seminary priests and Jesuits to leave Ireland by December 10 and directed the Irish laity that they had to attend services of the (Protestant) Church of Ireland.

These proclamations broadly paralleled the restrictions placed on Catholics in England. England had long had laws requiring everyone to attend (Protestant) Church of England services, along with a regulation– sometimes strictly enforced, sometimes less so– that anyone not doing so needed to pay what was called a “recusancy fee.” Back in February 1604 James had ordered all Jesuits and all other Catholic priests to leave England, and had reimposed the collection of fines for recusancy, which had grown a littler lax. English-WP tells us that in 1605, “There were 5,560 convicted of recusancy… of whom 112 were landowners. The very few Catholics of great wealth who refused to attend services at their parish church were fined £20 per month. Those of more moderate means had to pay two-thirds of their annual rental income; middle class recusants were fined one shilling a week, although the collection of all these fines was ‘haphazard and negligent’.”

So, the Guy Fawkes plot…

The main instigator– according to information dragged out of the conspirators afterwards through heinous tortures such as the “rack”– was a guy called Robert Catesby who was some kind of gentleman farmer in the English Midlands, and also a Catholic. He had been part of the Earl of Essex’s rebellion of 1601, but had paid a fine to escape a jail sentence. In 1603 he had traveled to Spain to seek Spanish King Philip III’s help in overthrowing the English monarchy; but Philip turned him down, preferring to make peace with London. So Catesby returned home and started hatching his plot.

The plan was, at the time of the opening of the English parliament in Westminster on November 5, 1605, to blow up the chamber of the House of Lords which on that occasion would be filled with not only all the Lords, Dukes, Earls, and so on but also King James and most of his family. But not all his family. The king’s 9-year-old daughter Princess Elizabeth was being raised in a country home not far from Catesby’s place in the Midlands, and the plot crucially relied on the plotters kidnapping her and using her as a figurehead of “legitimacy” for them in the post-James era.

The man deputized to install the many kegs of gunpowder in the basement under the House of Lords was Guy Fawkes. But the plot was discovered just the night before , due to a carelessly-worded letter the plotters had sent around too widely.

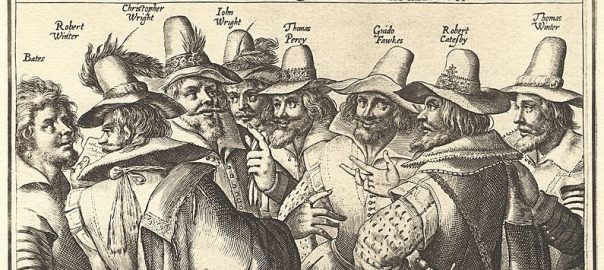

(The banner at the top of this page is an engraving of “Guido” Fawkes and eight other key participants in the plot.)

There was some speculation afterwards that the king’s wily Secretary of State Robert Cecil (now the Earl of Salisbury) had “allowed” the plot to continue almost to completion and then had seen to it that it should be the king himself who discovered it. (We could call this the “Erdogan 2016 maneuver”?)

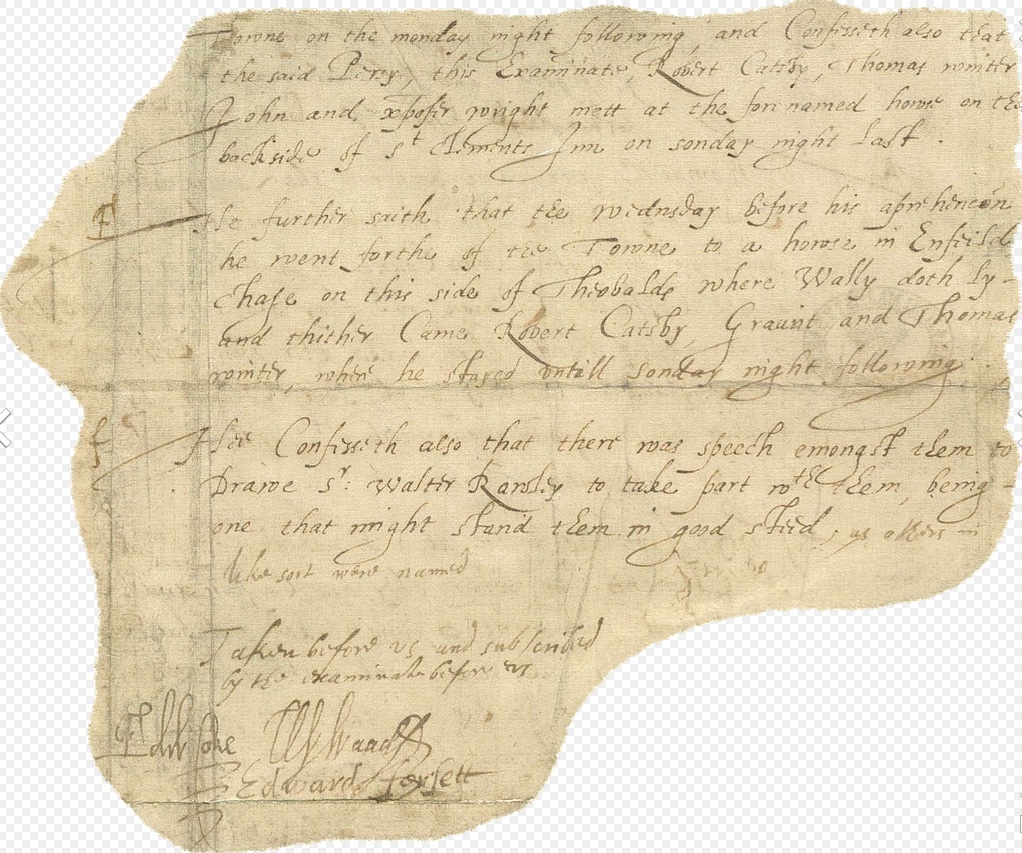

Anyway, once it was discovered, some king’s men were sent to the Midlands where there was a fight in which Catesby was killed; and meantime the plotters were rounded up throughout London and the Midlands.

The plotters were tried in Westminster Hall before a “jury” containing Cecil/Salisbury and four other Lords. At least eleven men were found guilty of treason in the trial. One of them was Henry Garnet, the chief Jesuit in England. Cateby and one other conspirator “escaped the executioner”, but their bodies were “exhumed and decapitated, and their heads exhibited on spikes outside the House of Lords.” Here’s what happened to the others:

On a cold 30 January, Everard Digby, Robert Wintour, John Grant, and Thomas Bates, were tied to hurdles—wooden panels—and dragged through the crowded streets of London to St Paul’s Churchyard. Digby, the first to mount the scaffold, asked the spectators for forgiveness, and refused the attentions of a Protestant clergyman. He was stripped of his clothing, and wearing only a shirt, climbed the ladder to place his head through the noose. He was quickly cut down, and while still fully conscious was castrated, disembowelled, and then quartered, along with the three other prisoners. The following day, Thomas Wintour, Ambrose Rookwood, Robert Keyes, and Guy Fawkes were hanged, drawn and quartered, opposite the building they had planned to blow up, in the Old Palace Yard at Westminster. Keyes did not wait for the hangman’s command and jumped from the gallows, but he survived the drop and was led to the quartering block. Although weakened by his torture, Fawkes managed to jump from the gallows and break his neck, thus avoiding the agony of the gruesome latter part of his execution.

Steven Littleton was executed at Stafford. His cousin Humphrey, despite his co-operation with the authorities, met his end at Red Hill near Worcester. Henry Garnet’s execution took place on 3 May 1606.

Mughal Empire’s Akbar dies, leaves big political legacy

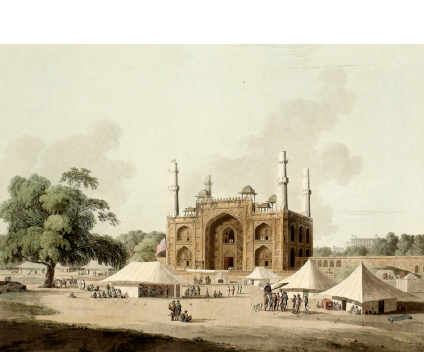

And now, to the Mughal capital of Fatehpur Sikri. On October 27, 1605, Emperor Akbar died of dysentery and was buried in his mausoleum in Sikandra, Agra. He was succeeded, peacefuylly, by his 36-year-old son Jahangir. But soon after, he “had to fend off his own son, Prince Khusrau Mirza, when the latter attempted to claim the throne based on Akbar’s will to become his next heir. Khusrau Mirza was defeated in 1606 and confined in the fort of Agra. As punishment, Khusrau Mirza was handed over to his younger brother and was partially blinded and killed.”

But since Akbar had had a long (49-year) reign and a lot of empire-building achievements, let us see how English-WP summarized his legacy. (The summary they provide indicates how heavily this issue is contested, but provides a variety of points of view.)

Akbar left a rich legacy both for the Mughal Empire as well as the Indian subcontinent in general. He firmly entrenched the authority of the Mughal Empire in India and beyond, after it had been threatened by the Afghans during his father’s reign, establishing its military and diplomatic superiority. During his reign, the nature of the state changed to a secular and liberal one, with emphasis on cultural integration. He also introduced several far-sighted social reforms, including prohibiting sati, legalising widow remarriage and raising the age of marriage. Folk tales revolving around him and Birbal, one of his navratnas, are popular in India.

Bhavishya Purana is a minor Purana that… includes a section devoted to the various dynasties that ruled India, dating its oldest portion to 500 CE and newest to the 18th century. It contains a story about Akbar in which he is compared to the other Mughal rulers. The section called “Akbar Bahshaha Varnan”, written in Sanskrit, describes his birth as a “reincarnation” of a sage who immolated himself on seeing the first Mughal ruler Babur, who is described as the “cruel king of Mlecchas (Muslims)”. In this text it is stated that Akbar “was a miraculous child” and that he would not follow the previous “violent ways” of the Mughals.

Citing Akbar’s melding of the disparate ‘fiefdoms’ of India into the Mughal Empire as well as the lasting legacy of “pluralism and tolerance” that “underlies the values of the modern republic of India”, Time magazine included his name in its list of top 25 world leaders.

On the other hand, his legacy is explicitly negative in Pakistan for the same reasons. Historian Mubarak Ali, while studying the image of Akbar in Pakistani textbooks, observes that Akbar “is conveniently ignored and not mentioned in any school textbook from class one to matriculation”, as opposed to the omnipresence of emperor Aurangzeb. He quotes historian Ishtiaq Hussain Qureshi, who said that, due to his religious tolerance, “Akbar had so weakened Islam through his policies that it could not be restored to its dominant position in the affairs.” … [A]fter analyzing many textbooks, Mubarak Ali says that “Akbar is criticized for bringing Muslims and Hindus together as one nation and putting the separate identity of the Muslims in danger. This policy of Akbar contradicts the theory of Two-Nation and therefore makes him an unpopular figure in Pakistan.”

Cardinals come to blows when choosing 2nd new pope this year

Whoa, this is a complex story! By now the Roman Catholic Pope had few temporal powers (except for lots of lands and money), but clearly the papacy still carried enormous symbolic value– if you were Catholic– so any time of papal succession was heavily fought over. And in 1605 there were two.

Pope Clement VIII, who came from a “prominent Florentine family”, had been in power since 1595. He had enacted various anti-Jewish measures in the lands he controlled and in around 1600 had endorsed the drinking of the new-fangled beverage of coffee, declaring: “Why, this Satan’s drink is so delicious that it would be a pity to let the infidels have exclusive use of it.” He died on March 3, 1605, “leaving a reputation for prudence, munificence, ruthlessness and capacity for business.” Cue the intense politicking in the 61-member college of cardinals over who should succeed him…

And the winner was Alessandro Ottaviano de’ Medici, who took the papal name Leo XI. “Leo’s election was seen as a victory for France because he was a relative of the French queen. After his election, supporters of the French crown celebrated in Rome’s streets.”

Then this: In late April he caught a cold while appearing in public– perhaps, while taking part in some of those celebrations aka super-spreader events? He died on April 27, just 26 days after his election.

In the next papal-election conclave, which started soon thereafter, the earliest front-runner was seen to be a guy called Domenico Toschi. But a bunch of other cardis opposed him. Thomas Hobbes later reported (was he there at the time, I wonder?) that some of this opposition was “based on Toschi’s frequent usage of the word cazzo, Lombard slang for penis.” When this accusation was leveled at Toschi, “This led to a physical altercation between the two sides that could be heard on the streets outside the conclave. The fight resulted in the only known instance of serious injury being suffered in a conclave with Alfonso Visconti having several broken bones.”

The cardinals speedily decided that to smooth things over they needed a compromise candidate. This was a guy called Camillo Borghese, who took the name Paul V. Among the factors seen in his favor were that (a) he was seen as fairly neutral between Spain and France, and (b) he was young enough, at 54, that the other cardinals hoped there need not be another papal-succession conclave any time soon. Whew!

Upheaval in Moscow; Polish nobles mount a coup

You thought leadership struggles were fraught in London or Rome? Well, now let’s go to Moscow…

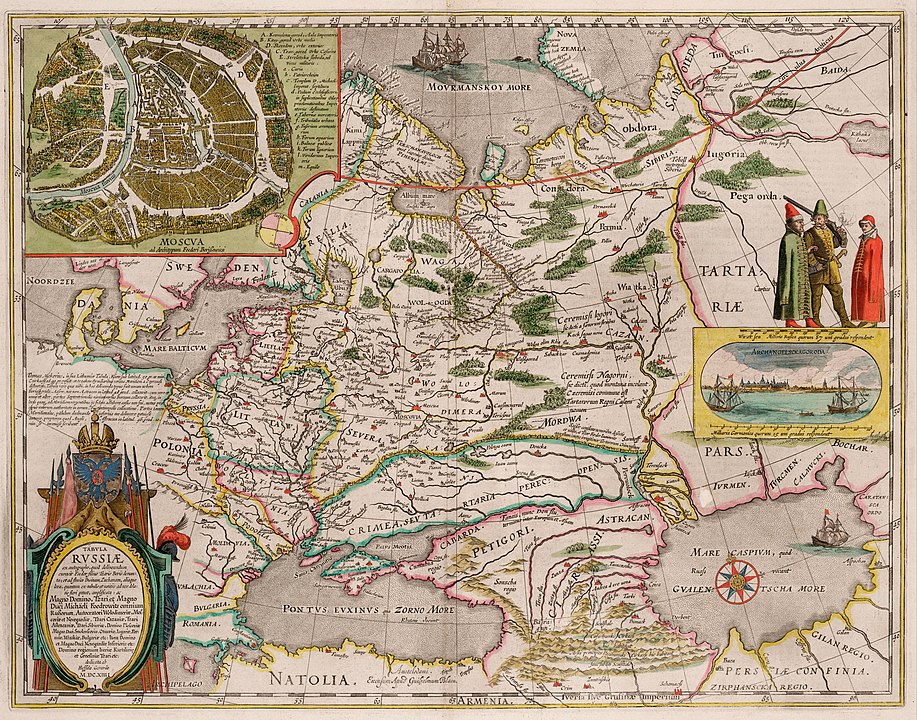

You will recall that after Ivan the Terrible’s son, Tsar Feodor I, died childless in 1598 the powerful First Brother-in-Law Boris Godunov had seized the reigns of power directly, declaring himself Tsar. In April 1605, the 54-year-old Godunov died, leaving one son, the intellectually talented 16-year-old Feodor, who was promptly crowned as Tsar Feodor II.

He lasted about seven weeks. On June 11, the envoys of a guy called False Dimitri I arrived in Moscow, demanding his removal. False Dimitri I?? Who was this guy? He was actually the first of three pretenders to the Russian throne who each claimed to be the “real” Prince Dimitri, that is, the long-lost youngest son of Ivan the T. The actual Prince Dimitri had, it has always been pretty clear, died at a young age– perhaps at Boris Godunov’s hand?– back in 1589. But now, here was this guy, Self-proclaimed Dimitri (Russian: самозванец; romanized: samozvanets) who arrived in Moscow with the help of some powerful Polish-Lithuanian nobles who, along with some powerful Russian boyars, wanted to install him on the throne rather than Godunov’s son Feodor.

According to English-WP, this False Dimitri (and yes, there will be more… ), “entered history circa 1600, after making a positive impression on Patriarch Job of Moscow with his learning and assurance. Upon hearing of this, Tsar Boris Godunov ordered the young man to be seized and examined, whereupon Dmitry fled to… the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and subsequently entered the service of the Wiśniowieckis, a polonized Ruthenian family.”

Over the next few years, he consolidated a power-based in Poland, and in March 1605 he marched into Russia with an army of about 3,500 men. Then this:

Boris’s many enemies, including the southern Cossacks, joined Dmitry’s army on the long march to Moscow. Thus combined, these forces fought two engagements with reluctant Russian soldiers; winning the first, they captured Chernigov (modern Chernihiv), Putivl (Putyvl), Sevsk, and Kursk, but they badly lost the second battle, almost to the point of disintegrating. The young man’s cause was only saved when news of the sudden death of Boris Godunov on 13 April 1605 reached his troops in the aftermath.

With the unpopular tsar dead, the last impediment to Dmitry’s progress had been swept away; the victorious Russian troops defected to Dmitry’s side, followed soon by others, swelling the Polish ranks as they marched further in. Finally, on 1 June, the disaffected boyars of Moscow staged a palace coup, imprisoning newly crowned tsar Feodor II and his mother Maria Skuratova-Belskaya, the widow of Boris Godunov.

This other WP page tells us that “On June 10th or 20th, Feodor was strangled in his apartment, together with his mother.”

On June 20, False Dimiotri made a triumphal entry into Moscow and a month later he was crowned tsar by a new Patriarch of his own choosing. The only Godunov family member whom Dimitri did not have killed was Feodor II’s sister Xenia, “whom Dmitry raped, keeping her as a concubine for five months.”

Spoiler alert: Dimitri will not last long…

Spain plants yet more colonial settlements in “New Spain”

Let us not forget that while all those intriguing things were happening over recent years in the courts of d the Spice Islands of East Asia, the Spanish conquistadores were continuing their ruthless pursuit of their settler-colonial project in “the New [to them] World”. As evertywhere else, achivement of this project involved mass-scale genocidal violence against the Indigenes.

In 1605 alone, the conquistadores established the following settlements in “New Spain”:

- Ahome, on the Pacific coast of present-day Sinaloa, Mexico, which was founded by the Jesuits.

- Badiraguato, a little further inland in today’s Sinaloa.

- San Sebastián del Oeste, a little inland from the Pacific, in the present-day Mexican state of Jalisco. “San Sebastián was founded as a mining town in 1605, during the early Spanish colonial Viceroyalty of New Spain period. Gold, silver and lead were mined in the area. More than 25 mines and a number of foundries were established by 1785.”