Whoa, what a year, 1603 CE! Also, fwiw, two of the biggest events that year happened on… March 24. Serendipity or what?

So here’s the Table of Contents. The two March 24 events come first, why not?

- Queen Elizabeth dies, leaving interesting succession…

- Japanese emperor names Tokugawa as shōgun; Edo period begins

- Dutch VOC profitably captures Portuguese treasure ship, spurring key international law debate

- Large anti-Spanish rebellion in Philippines, brutally suppressed

- Safavid Shah Abbas hits back at Ottomans; Ottoman Sultan dies

- French explorer plants colony at Acadia.

Queen Elizabeth dies, leaving interesting succession…

Well here she was, the proudly “Virgin” queen, 69 years old and feeling her age… and, obviously, without issue. Her Secretary of State, Robert Cecil, had been keenly aware of the challenges this posed to the monarchy for several years by now. He had been born in 1563, was a protege of her wily earlier spymaster Francis Walsingham, and had inherited the position of Secretary of State from his father.

Here’s what English-WP says about Cecil, who in an era that glorified physical attractiveness was notably small in stature and had scoliosis that bowed his back:

Cecil, like his father, greatly admired the Queen, whom he famously described as being “more than a man, but less than a woman” [whoa, nice that!!] Despite his careful preparations for the succession, he clearly regarded the Queen’s death as a misfortune to be postponed as long as possible. During her last illness, when Elizabeth would sit motionless on cushions for hours on end, Cecil boldly told her that she must go to bed. Elizabeth roused herself one last time to snap at him: “Little man, little man, ‘Must’ is not a word to use to princes. Your father were he here durst never speak to me so”; but she added wryly “Ah, but ye know that I must die, and it makes you presumptuous”.

In the succession battle to come, Cecil favored James VI of Scotland, a cousin of Elizabeth’s who in his infancy had been snatched by the English and their allies from the arms of his mother, Mary Queen of Scots, and who was sitting in Scotland awaiting Cecil’s call.

Cecil had reached an understanding with James that so long as Elizabeth was alive James should not be too forward in pushing his claim to her throne, but that Cecil would orchestrate things for him from behind the scenes. Which was what he did.

The queen finally died on March 24.

Actually, the main opposition to James’s claim came from Cecil’s own brothers-in-law, Henry Brooke (Lord Cobham) and Sir George Brooke, along with Sir Walter Raleigh, whose plot aimed to remove James from the throne and replace him with his first cousin, Lady Arbella Stuart. But Cecil had not studied with Walsingham for nothing and was able to foil the plot, arresting him and the other conspirators that July. Cobham and Raleigh were not executed for their alleged (but ill-proven) sedition, though they were both imprisoned. Some of their co-conspirators were executed.

But meantime, James– to whom Elizabeth had been paying a subsidy since 1586– had taken a slow journey down to London. This page on WP tells us:

Local lords received him with lavish hospitality along the route and James was amazed by the wealth of his new land and subjects, claiming that he was “swapping a stony couch for a deep feather bed”. James arrived in the capital on 7 May, nine days after Elizabeth’s funeral. His new subjects flocked to see him, relieved that the succession had triggered neither unrest nor invasion. On arrival at London, he was mobbed by a crowd of spectators.

His English coronation [as James I] took place on 25 July, with elaborate allegories provided by dramatic poets such as Thomas Dekker and Ben Jonson. An outbreak of plague restricted festivities, but “the streets seemed paved with men,” wrote Dekker. “Stalls instead of rich wares were set out with children, open casements filled up with women.”

England’s new King James I inaugurated the “Stuart” era of English monarchs. His desire to unify the two crowns completely– well, actually three, since the English crown had already completely ingested a now large notional “Irish” crown– met with continuing resistance.

But he and Cecil (whom he immediately elevated to become “Baron Cecil of Essenden”) seemed to agree on pursuing a peaceable policy toward the Spanish. Soon after the coronation, James and Cecil started negotiations for a peace treaty with Spain which was concluded in London in May 1604. That treaty would bring to an end a period of intense conflict between England and Spain that had lasted nineteen years– or much longer, depending how you look at it.

Japanese emperor names Tokugawa as shōgun; Edo period begins

This, almost wholly from WP:

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the Edo shogunate was established by the military leader Tokugawa Ieyasu after his victory at the Battle of Sekigahara, which ended the civil wars that had followed the collapse of the Ashikaga shogunate.

Tokugawa Ieyasu became the shōgun, Japan’s chief military leader, and the Tokugawa clan governed the country from Edo Castle in the eastern city of Edo (today’s Tokyo) along with the daimyō lords of the samurai class. The Tokugawa shogunate organized Japanese society under the strict Tokugawa class system and banned most foreigners under the isolationist policies of Sakoku to promote political stability. The Tokugawa shoguns governed Japan in a feudal system, with each daimyō administering a han (feudal domain), although the country was still nominally organized as imperial provinces. Under the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan experienced rapid economic growth and urbanization, which led to the rise of the merchant class and the plesure-seeking Ukiyo culture.

The Tokugawa shogunate declined during the period from 1853 on and was overthrown by supporters of the Imperial Court in the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

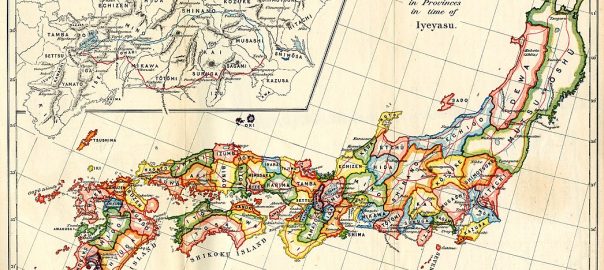

By the way, the map at the top of this post is of Japan in this era.

Dutch VOC profitably captures Portuguese treasure ship, spurring key international law debate

The Dutch investors’ East-Indies exploration and expeditionary company, the VOC, had only been incorporated in 1602. Now, in February 1603 a group of three VOC ships spotted a heavily-laden Portuguese trading ship, the Santa Catarina, off the coast of today’s Singapore and attacked it. The Portuguese ship was traveling from Macau to Malacca, “loaded with products from China and Japan, including 1200 bales of Chinese raw silk, worth 2.2 million guilders. The cargo was particularly valuable because it contained several hundred ounces of musk. After a couple of hours of fighting, the Dutch managed to subdue the crew who forfeited the cargo and the ship, in return for the safety of their lives.”

The VOC captains took the Santa Catarina back to Amsterdam, where it was met with general rejoicing. The acquisition of the the ship and its cargo increased the VOC’s already large pot of capital by more than 50%!

But was it legal? It is not clear to me whether Portugal/Spain and the UP’s were already at war when the ship-jacking took place. (I guess they were?) But even if so, was simply capturing a merchant ship belonging to an “enemy” nation on the high seas a legitimate act of war?

The Portuguese evidently thought not. Many of the VOC’s investors said, “Absolutely, yes!” But another portion of them– reportedly mostly Mennonites– objected to the ship’s capture on moral grounds. So the still-young Netherlands political system decided to hold a public judicial hearing… and to argue its case for legality, the VOC brought in a very precocious 20-year-old jurist who had already started to make his name in international law: Hugo Grotius.

This page on WP explains the impact of what happened then:

Grotius sought to ground his defense of the seizure in terms of the natural principles of justice. One chapter of his long theory-laden treatise entitled De Jure Prædæ made it to the press in the form of the influential pamphlet, Mare Liberum (The Free Sea).

In Mare Liberum, published in 1609, Grotius adapted the principle originally formulated by Francisco de Vitoria and further developed by Fernando Vazquez de Menchaca (cf. the School of Salamanca), that the sea was international territory, against the Portuguese Mare Clausum (closed sea) policy, and all nations were free to use it for seafaring trade. Grotius, by claiming ‘free seas’, provided suitable ideological justification for the Dutch breaking up of various trade monopolies through its formidable naval power.

England, competing fiercely with the Dutch for domination of world trade, opposed this idea, redefining the Mare Clausum principles. As conflicting claims grew out of the controversy, maritime states came to moderate their demands and base their maritime claims on the principle that it extended seawards from land. A workable formula was found by Cornelius Bynkershoek in his De dominio maris (1702), restricting maritime dominion to the actual distance within which cannon range could effectively protect it. This became universally adopted and developed into the three-mile limit.

Oh, and by the way on September 4, 1604, the Amsterdam Admiralty Court ruled in favor of the VOC. I imagine Grotius got a nice bonus that year?

Large anti-Spanish rebellion in Philippines, brutally suppressed

And still in East Asia… The Captaincy General of the Philippines that the Spanish had established in Manila in 1584 had not gone un-noticed or unopposed by other political powers in the region. And nor had the Spanish colonizers been content with just their initial little colony. Among other expansion plans, throughout the 1590s, they had attempted to invade Cambodia a number of times; but in 1599, “Malay Muslim merchants defeated and massacred almost the entire contingent of Spanish troops in Cambodia, putting an end to the Spanish plans to conquer it.”

The Ming Chinese (and other Chinese actors) were unsettled by the Spanish colonizers’ presence and their expansionist plans. In October 1603, there was a large-scale uprising in Manila itself of people of joint Chinese-Filipino ancestry known locally as “Sangley”. WP tells us:

The reasons for the rebellion are unclear, but they seemed to have originated in the suspicions of the Archbishop of Manila… that the Chinese had ambitions to control the Philippines.

The Governor-General of the Philippines and failed conqueror of Cambodia, Luis Pérez Dasmariñas, died during the rebellion when, overconfident of Spanish strength, he attacked the Chinese. When cautioned from attacking by his fellow officers, he famously derided them as cowards and retorted that “twenty five Spaniards were enough to conquer the whole of China”. When Dasmariñas led a force of Spaniards to try to apprehend the Chinese, he and his men were all killed by the Chinese who mounted the Spanish heads they chopped off throughout Manila.

The rebellion was then quelled by the Spaniards, together with the support of Filipinos and the Japanese in the settlement of Dilao. The Japanese were considered especially harsh in their efforts to crush the rebellion, as compared to the Spanish and Filipinos. Altogether 20,000 Chinese were killed. In 1639, the Spanish carried out another massacre, killing 24,000 Chinese.

Safavid Shah Abbas hits back at Ottomans; Ottoman Sultan dies

Back in 1589-90, Persia’s newly installed Shah Abbas I had made the tough decision to cut his empire’s losses in the lengthy and unsuccessful war his predecessors had waged against the Ottomans and to conclude a fairly humiliating peace treaty with Istanbul. Now, in 1603, he was ready to try to regain the territories lost earlier.

Let’s take it from here:

Abbas I had recently undertaken a major reform of the Safavid army through the English gentleman of fortune Robert Shirley [brother of the incompetent Englishman Abbas had tried to use as a diplomat in 1589], and the shah’s favorite ghulam and chancellor Allahverdi Khan.

… [T]he Ottomans were engaged heavily in the European front due to the Long Turkish War started in 1593. Furthermore, the Ottomans were troubled in Eastern Anatolia because of the Jelali revolts… Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire was also in turmoil in the beginning of 1603 as the tension between the Janissaries and the Sipahis were only to be eased temporarily with the intervention of the Palace.

Thus, the Safavid attack on 26 September 1603 caught the Ottomans unprepared and forced them to fight in two distant fronts. Abbas I first recaptured Nahavand and destroyed the fortress in the city, which the Ottomans had planned to use as an advance base for attacks on Iran. The Safavid army was able to capture Tabriz on 21 October 1603. For the first time, the Iranians made great use of their artillery and the town – which had been ruined by Ottoman occupation – soon fell. Local citizens welcomed the Safavid army as liberators and took harsh reprisals against the defeated Ottoman Turks who had been occupying their city. Many unfortunate Turks fell into the hands of Tabriz’s citizens and were decapitated. The Safavids entered Nakhchivan at the same month soon after the city was evacuated by the Ottomans. The Safavid army then laid siege to Yerevan on 15 November 1603. Safavid armies captured Tbilisi and both Kartli and Kakheti became Safavid dependencies once again.

Well, this speedy series of losses was probably a real blow for the 37-year-old Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed III. He died on December 22, 1603. “According to one source, the cause of his death was the distress caused by the death of his son, Şehzade Mahmud. According to another source, he died either of plague or of stroke. He was buried in Hagia Sophia Mosque. He was succeeded by his son Ahmed I as the new sultan.”

And wow, here’s something new in Istanbul: The new sultan did not immediately have all his remaining brothers butchered!

Ahmed I was only 13 years old on his succession, so almost certainly any authority there was in Istanbul was exercised by the Grand Vizier, Yavuz Ali Pasha (a.k.a. Malkoç Ali Pasha.) But Yavuz Ali was not the same kind of very experienced and powerful court insider that Istanbul had seen earlier in, for example, Sokollu Mehmed Pasha. In fact, when Mehmed died, Yavuz Ali was still Governor of Egypt, so he had to rush back to Istanbul to help with the transition and with regent-ing for Ahmed. (“He brought with him two years’ worth of the [Egyptian] province’s back taxes.”)

The Ottoman empire was trying to fight wars on two fronts. In summer 1604, Yavuz Ali made the decision to travel to the central European front against the Habsburgs to try to strengthen the Ottoman forces’ position there. But he fell sick en route and died in Belgrade in July 1604.

Let’s see how things go for the young new Sultan after that…

French explorer plants colony at Acadia.

Looking back from today over the era of the domination of the world order by countries of West-European origin we know that France was for a long time quite the active participant. But at the dawn of the 17th century CE, French colonial activities are almost nowhere to be found. (Indeed, the English and Dutch efforts are only just starting seriously to emerge.)

A man from a seafaring family in Brittany called Samuel Champlain, born in 1567 was determined to change that. He took his first trip to North America in 1603, in a ship captained by his uncle, François Gravé Du Pont, the Bonne-Renommée, the “Good Fame“, which reached Tadoussac (in today’s Quebec province) on March 15, 1603:

Champlain was anxious to see for himself all of the places that Jacques Cartier had seen and described about sixty years earlier, and wanted to go even further than Cartier, if possible. Champlain created a map of the Saint Lawrence on this trip and, after his return to France on 20 September, published an account as Des Sauvages: ou voyage de Samuel Champlain, de Brouages, faite en la France nouvelle l’an 1603 (“Concerning the Savages: or travels of Samuel Champlain of Brouages, made in New France in the year 1603”). Included in his account were meetings with Begourat, a chief of the Montagnais at Tadoussac, in which positive relationships were established between the French and the many Montagnais gathered there, with some Algonquin friends.

After 1603, Champlain’s life and career consolidated into the path he would follow for the rest of his life. From 1604 to 1607, he participated in the exploration and settlement of the first permanent European settlement north of Florida, Port Royal, Acadia (1605), as well as the first European settlement that would become Saint John, New Brunswick (1604). In 1608, he established the French settlement that is now Quebec City. Champlain was the first European to describe the Great Lakes, and published maps of his journeys and accounts of what he learned from the natives and the French living among the Natives.