I realize I’ve been pretty England-heavy recently, so today I’ll start with the coming of the Safavid Empire’s Shah Abbas. Since it is International Women’s Day, I thought I should look for some women’s news from 1587 CE. The main item in that department has to be the execution in February 1587 of Mary, Queen of Scots, by order of her cousin-by-marriage Queen Elizabeth. Enough women protagonists involved there? I think so!

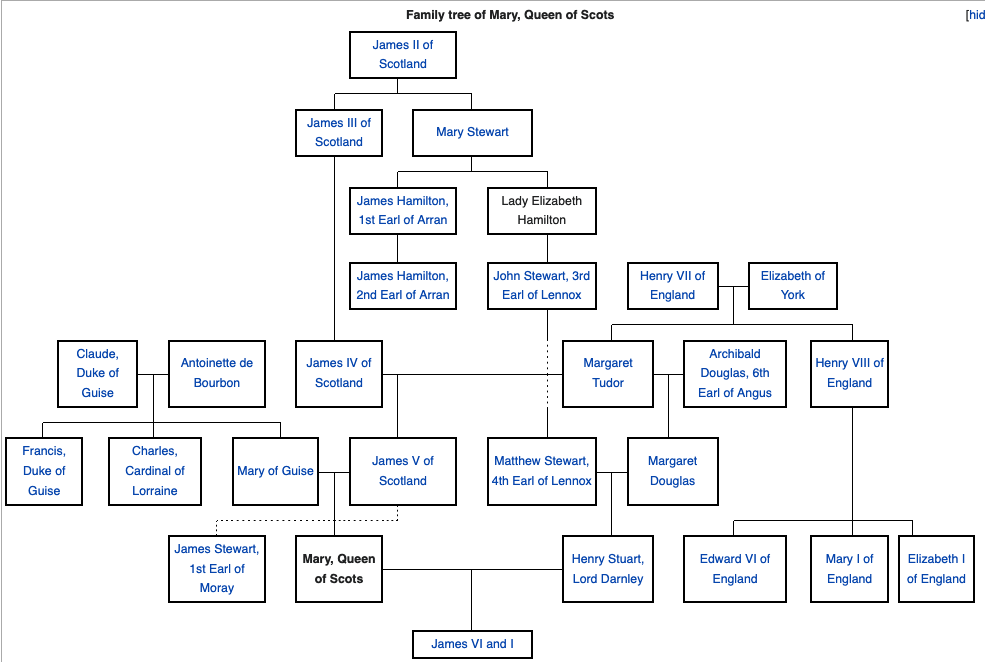

By the way, WP has this handy family tree, at right, showing the family connection between the two queens.

(Also, Anne Seymour, née Stanhope, Duchess of Somerset, died in April 1587. She was described as “briefly the most powerful woman in England”, during the time her spouse the Duke of Somerset was the regent and Lord Protector for their nephew King Edward VI. Her tomb in Westminster Abbey is shown above.)

Safavid Iran gets a new Shah

Since 1578, Iran had been ruled by the weak– and almost blind– Shah Mohammad Khodābandeh, during whose reign the country had suffered serious invasions from both northwest (Ottomans) and northeast (Uzbeks.) During the first year of Muhammad K’s reign, his wife Khayr al-Nisa Begum came to dominate the government, attracting the ire of the still-powerful Qizilbash chieftains. On July 26, 1579, some of them stormed the harem and strangled her and her mother, accusing Khayr al-Nisa of conducting having a love affair with Adil Giray, brother of the Crimean Tatar Khan, who was being held captive at the Safavid court. Whoa. True “Real Housewives of Qazvin” stuff going on there.

Little Abbas had been born in Herat, in 1571, and was Mohammad and Khayr al-Nisa’s third son. When he was four, his still-ruling grandfather Tahmasp decided Muhammad K needed to go to Shiraz, for health reasons. Abbas was left behind in Herat as nominal “governor” of Khorasan province.

Enhglish-WP tells us that in 1585, Abbas came under the the guardianship of Murshid Qoli Khan, one of the Qizilbash leaders in Khorasan:

When a large Uzbek army invaded Khorasan in 1587, Murshid decided the time was right to overthrow Shah Mohammad. He rode to the capital of Qazvin with the young prince and pronounced him king on 16 October 1587. Mohammad made no objection against his deposition and handed the royal insignia over to his son during the following year on 1 October 1588, when Abbas was 17.

The kingdom Abbas inherited was in a desperate state. The Ottomans had seized vast territories in the west and the north-west (including the major city of Tabriz) and the Uzbeks had overrun half of Khorasan in the north-east. Iran itself was riven by fighting between the various factions of the Qizilbash, who had mocked royal authority by killing the queen in 1579 and the grand vizier Mirza Salman Jabiri in 1583.

In future years we will come to learn how Abbas acquired the monicker “the Great”…

Francis Drake singes the King of Spain’s beard

Once Queen Elizabeth’s expert spymaster had uncovered and blocked the Spanish/Catholic plot against her reign, she clearly had good reason to fear that the Spaniards’ next move against her would likely be a full-fledged naval assault. So in early 1587, around the same time she had Mary, Queen of Scots executed, Queen Elizabeth gave expert English mariner (and sometime pirate/privateer) Francis Drake command of a fleet whose mission was “to inspect the Spanish military preparations, intercept their supplies, attack the fleet and if possible the Spanish ports.” To that end, she put at Drake’s disposal four Royal Naval galleons. An additional twenty merchantmen and “armed pinnaces” joined the expedition.

English-WP tells us that, “The cost of these boats was met by a group of London merchants, whose profits were to be calculated in the same proportions as their investment in the fleet; the Queen, as owner of the four Royal Naval vessels, was to receive 50% of the profits.”

Clearly, “intercepting the supplies” of the Spaniards was intended to mean “steal as much as you can get.”

On 12 April 1587,

the English fleet set sail from Plymouth. Seven days after their departure, the Queen sent a counter-command to Drake with instructions not to commence hostilities against the Spanish Fleet or ports. Drake never received this order as the boat carrying it was forced back into port by headwinds before it was able to reach him. Queen Elizabeth had in fact never intended for this note to reach Drake in time and was part of the usual process in which Elizabeth could have plausible deniability over Drake’s actions should they not go exactly to plan.

(By the way, she had done the exact same thing with the order to execute MQS. I’d call that kind of deniability pretty implausible?)

By April 29, Drake’s little fleet had reached the Bay of Cadiz where over the next 36 hours they destroyed “27 or 37 Spanish ships, with a combined capacity of 10,000 tons. Furthermore, they had captured four other ships, laden with provisions.”

They then sailed further on down the Spanish/Portuguese coastline, storming various fortresses as they went. Drake then decided to see what he could pick up in the Spanish/Portuguese-controlled Azores and struck it really rich. On June 8, he was able to capture a Portuguese carrack, the São Filipe, that was returning from the Indies laden with treasure. That was the first such capture, and extremely profitable for all the investors in Drake’s trip: “Its enormous fortune of gold, spices, and silk was valued at £108,000 (of which 10% was to go to Drake); the fleet returned to England, arriving on 6 July.”

As WP notes:

Drake had already embarrassed King Philip with his actions in the West Indies, taking towns and ships at will from the pre-eminent naval power of the time. With this expedition, he had taken that affront to Philip’s doorstep, raiding along the very coast of Spain, and laying up with impunity for three days in Spain’s premier Atlantic port while he burned ships and stores. These actions gave heart to Spain’s enemies and dismayed her friends. Drake compounded the insult by publicly boasting that he had “singed the King of Spain’s beard”; yet privately he realized that his actions had only delayed a Spanish invasion, not prevented it altogether, and he wrote to Elizabeth urging her to “Prepare in England strongly, and mostly by sea. Stop him now and stop him forever”.