A big year, 1555 CE! Let’s dive right in:

- On a world-historical scale, maybe the biggest thing happening in 1555 was that Spain’s King/Emperor Charles was at the height of a two-year process he’d started in 1554, of undertaking abdications from his many offices, titles, and kingdoms. Abdications in the plural, you might ask? Indeed yes. (See here for more details… ) Basically, he had inherited from his grandparents the title to numerous kingdoms dotted across Europe, not just Ferdinand and Isabella’s domain in Castile+Aragon; and he’d also inherited (or himself developed?) an idea of being a “universal” ruler– “Holy Roman Emperor.” Oh, and then there was the process of building a massive transatlantic empire for Spain in the Americas, which had continued to grow apace since he became King of Spain, age 16, back in 1516. But by 1555 he was starting to feel his age. English-WP tells us: “According to scholars, Charles decided to abdicate for a variety of reasons: the religious division of Germany sanctioned in 1555; the state of Spanish finances, bankrupted with inflation by the time his reign ended; the revival of Italian Wars with attacks from Henri II of France; the never-ending advance of the Ottomans in the Mediterranean and central Europe; and his declining health, in particular attacks of gout such as the one that forced him to postpone an attempt to recapture the city of Metz where he was later defeated.” In his principal abdication speech he spoke of how far and how often he had traveled in. pursuit of his duties: “My life has been one long journey.” Notably, though, he’d never journeyed to the Americas– and that had left the rapacious conquistadores there free to wreak their havoc more or less as they wanted, with few constraints. Bottom line on the abdications: He left nearly all his domains to his son Philip II (also recently married to England’s Queen Mary.) But the “Holy Roman Empire” bit he left to his brother Ferdinand. I’d love to explore the meaning of his abdications more here but have no time to. Above, see part of an allegorical painting of Charles’s abdication(s) of 1555 by Frans Francken the Younger.

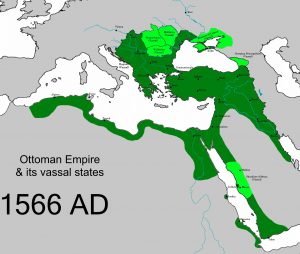

Or maybe the biggest thing that happened in 1555 was the Peace of Amasya concluded between Safavid Iran and the Ottomans? “The treaty defined the border between Iran and the Ottoman Empire and was followed by twenty years of peace. By this treaty, Armenia and Georgia were divided equally between the two, with Western Armenia, western Kurdistan, and western Georgia (incl. western Samtskhe) falling in Ottoman hands while Eastern Armenia, eastern Kurdistan, and eastern Georgia (incl. eastern Samtskhe) stayed in Iranian hands. The Ottoman Empire obtained most of Iraq, including Baghdad, which gave them access to the Persian Gulf, while the Persians retained their former capital Tabriz and all their other northwestern territories in the Caucasus and as they were prior to the wars, such as Dagestan and all of what is now Azerbaijan... Another term of the treaty was that the Safavids were required to end the ritual cursing of the first three Rashidun Caliphs, Aisha and other Sahaba (companions of Muhammad) — all held in high esteem by Sunnis.”

Or maybe the biggest thing that happened in 1555 was the Peace of Amasya concluded between Safavid Iran and the Ottomans? “The treaty defined the border between Iran and the Ottoman Empire and was followed by twenty years of peace. By this treaty, Armenia and Georgia were divided equally between the two, with Western Armenia, western Kurdistan, and western Georgia (incl. western Samtskhe) falling in Ottoman hands while Eastern Armenia, eastern Kurdistan, and eastern Georgia (incl. eastern Samtskhe) stayed in Iranian hands. The Ottoman Empire obtained most of Iraq, including Baghdad, which gave them access to the Persian Gulf, while the Persians retained their former capital Tabriz and all their other northwestern territories in the Caucasus and as they were prior to the wars, such as Dagestan and all of what is now Azerbaijan... Another term of the treaty was that the Safavids were required to end the ritual cursing of the first three Rashidun Caliphs, Aisha and other Sahaba (companions of Muhammad) — all held in high esteem by Sunnis.”-

Detail of a miniature of Humayun in the Baburnama Or maybe, the biggest thing was a great victory on another front for the Safavids: The restoration (with their considerable help) of the former Mughal Emperor Humayun who had been ousted from his empire by Sher Shah Suri back in 1530. Humayun’s adventures and travails while in exile had been numerous– with most of the travails occurring at the hands of his also-exiled brothers. But at the June 1555 Battle of Sirhind, a Humayun-loyal force estimated at 100,000 defeated the Suri forces and Mughal power was restored over most of India. The Safavid shah, Tahmasp, reportedly provided “12,000 cavalry and 300 veterans of his personal guard” to support at least the first stage of Humayun’s restoration (and asked Humayun’s people to convert to Shiism, which I don’t think they did.) To win his victory, Humayun had to battle and defeat all his brothers along the way. But back in 1542, he had had a son, Akbar, the date and location of whose birth was deemed extremely auspicious…

-

Adal Sultanate at its greatest extent Other troubling news for the Ottomans in 1555 was that the Adal Sultanate in the Horn of Africa, with which they had been allied, was collapsing.

- In Mary I’s England, meanwhile, the burning at the stake of various anti-Catholic intellectuals, bishops, and thinkers was accelerating. Mary had the first of a couple of false pregnancies– which boded ill for her ambition of producing a nicely Catholic heir along with her husband, Philip II of Spain.

- But nearly independently of any royal control, English overseas adventurers continued to slowly push forward their transcontinental explorations. Richard Chancellor of the newly chartered Muscovy Company negotiated a trade agreement with Tsar Ivan of Russia. And the English sea-captain John Lok, who had earlier traveled (I believe by sea?) to Jerusalem, now returned to an English port– London? Bristol?– after a half-year journey to Guinea, in West Africa. His flotilla of three ships had made landfall at a number of places along the Guinea coast (and lost 24 seaman along the way.) English-WP tells us that the cargo Lok returned with, “included more than 400 pounds’ weight of gold, 36 butts of Guinea pepper, and 250 elephants’ tusks, as well as an elephant’s skull of such size and weight that a man could scarcely lift it. Lok’s ships also brought home five Africans from present-day Ghana to learn English and act as interpreters on future trading voyages to Guinea.” No word on whether the five Africans had joined the ships voluntarily, but somehow I doubt it. (This Lok’s collateral descendant John Locke, born 1632, would become a prime theoretician of English empiricism, political liberalism… and justifications for chattel slavery.)