So, in 1522 CE, our story of the development of Western imperialism continues to focus on many of the same actors as we were tracing the past two years:

- In January, and on behalf of “Spain” (more precisely, perhaps, the union of Castile and Aragon inaugurated by the 1469 marriage of Ferdinand and Isabella), the conquistador Gil González Dávila set out from the Pacific coast of Panama to explore some of the rest of that coast. He explored Nicaragua and named Costa Rica when he found lots of gold on the beaches.

- From July through December, Suleiman the Magnificent was besieging the island of Rhodes, stronghold of the Knights of St. John, a European Catholic military order that had played a big role in the crusades. Finally, on December 20, the Knights surrendered. Suleiman allowed them to evacuate to Malta where they regrouped for another few centuries.

- In August, something called the Knights’ Revolt broke out in Germany. It was a revolt against Catholic control by some German knights of Protestant or even humanist leanings. It only lasted nine months but presaged more Protestant rebelling to come.

- On September 6, the Vittoria, one of the surviving ships of Ferdinand Magellan‘s expedition, returned to Spain, becoming the first ship to circumnavigate the world. (In the 1521 post, I described Magellan as the first person to circumnavigate the globe, which perhaps is not strictly true– though close enough? He had sailed from Portugal around Africa to present-day Malaysia and returned the same way to Portugal. Some time later he sailed from Spain westwards around South America, and in a different ship, ending up in present-day Philippines where he was killed.)

- Later in September, Martin Luther‘s translation of the Bible’s New Testament from Greek into German, Das newe Testament Deutzsch, was published in Germany, selling thousands in the first few weeks. The Catholic hierarchy was still clearly struggling to find a way to deal with the challenge his activities posed.

- At some unknown point in 1522, Chinese (Ming dynasty) War Ministry official He Ru was the first to acquire the Portuguese breech-loading culverin, an innovative piece of weaponry that was the antecedent to both the musket and several big naval guns… while copies of culverins were also made by two Westernized Chinese in Beijing.

Some thoughts on beginnings, Portugal, and sources

I decided to launch this project in the last days of 2020, with the theme of “500 years ago”. That was why I started the daily postings here in 1520. But of course, all the stories I’ve been tracking here have important antecedents. U.S. Americans and other Westerners like to date the beginning of the “global” or modern era to 1492 CE, the year of the first contact between the Genoese mariner Christopher Columbus and the shoreline and peoples of what was later named the Americas. Columbus was sailing on behalf of Ferdinand and Isabella, who in that same year were able to capture Granada, the last of the previously numerous Muslim-ruled city-states in the Iberian Peninsula.

Columbus’s contact with the “New World” was of course momentous, inaugurating as it did a whole era of imperial expansion and imperial looting/rapine that helped to consolidate the emergence of a single and powerful Spanish state at home. However, Ferdinand and Isabella were not the first European powers to undertake armed, long-distance, maritime expeditions that established economic and trading outposts in places very, very far from Europe. That “honor” belonged to Portugal, another heavily Catholic state that grew up in the Iberian Peninsula in land “reconquered” from Muslim rulers– which in Portugal’s case has happened a 350 years before 1492, namely in 1139.

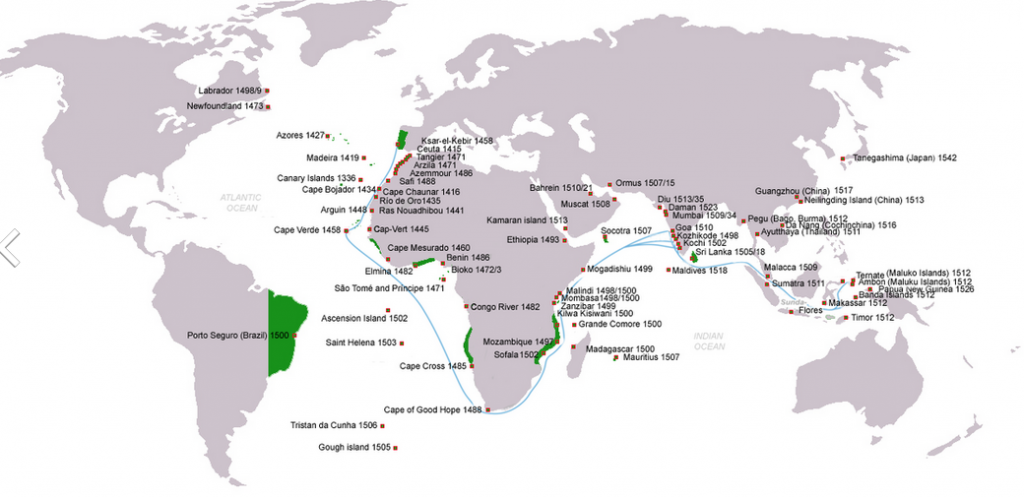

The first Portuguese naval expedition beyond Europe was the one that “Henry the Navigator” undertook in 1415, to capture from its Muslim ruler the rock-fortress of Ceuta, which lies just across the Straits of Gibraltar from Gibraltar, in present-day Morocco. (That’s a tilework portrat of the event, in the banner above.) The Wikipedia entry on the Portuguese Empire tells us that the main goal of nearly all of Portugal’s overseas expeditions was to establish trading-posts, not to control land. But Ceuta was not a good place for a trading-post, so Henry and the other Portuguese adventurers whom he financed and supported pushed on around the west coast of Africa to see what else they could find, exploring all the islands they discovered as they went, too.

Under Henry’s sponsorship, Portuguese mariners reached the Atlantic islands of Madeira (1419) and the Azores (1427.) In these islands, described as “largely unpopulated”, the Portuguese started to establish actual settlements, producing wheat for export to Portugal.

But, per Wikipedia, the Portuguese ships sailing down the west coast of Africa were soon,

bringing into the European market highly valued gold, ivory, pepper, cotton, sugar, and slaves. The slave trade, for example, was conducted by a few dozen merchants in Lisbon.

In the process of expanding the trade routes, Portuguese navigators mapped unknown parts of Africa, and began exploring the Indian Ocean. In 1487, an overland expedition by Pêro da Covilhã made its way to India, exploring trade opportunities with the Indians and Arabs, and winding up finally in Ethiopia. His detailed report was eagerly read in Lisbon, which became the best informed center for global geography and trade routes.

In 1452 and 1455, successive papal edicts gave Portugal a monopoly right to trade with these African lands. Also, per Wikipedia, “A major advance that accelerated this project was the introduction of the caravel in the mid-15th century, a ship that could be sailed closer to the wind than any other in operation in Europe at the time.”

While pushing down the west coast of Africa, the Portuguese were laying the basis not only for the transatlantic trade in enslaved persons that would mark the following 400 years but also the importance of sugar as a commodity much prized by European consumers. We will certainly be looking in more depth into the role that sugar played in the development of Western capitalism/imperialism, later on. But here’s what Wikipedia tells us about its 15th-century, Portuguese origins:

Expansion of sugarcane in Madeira started in 1455, using advisers from Sicily and (largely) Genoese capital to produce the “sweet salt” rare in Europe. Already cultivated in Algarve, the accessibility of Madeira attracted Genoese and Flemish traders keen to bypass Venetian monopolies. Slaves were used, and the proportion of imported slaves in Madeira reached 10% of the total population by the 16th century. By 1480 Antwerp had some seventy ships engaged in the Madeira sugar trade, with the refining and distribution concentrated in Antwerp. By the 1490s Madeira had overtaken Cyprus as a producer of sugar. The success of sugar merchants… would propel the investment in future travels.

These Portuguese sea-captains had also racked up other momentous navigational discoveries– 32 years before Magellan rounded the tip of South America in 1520: “In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope on the southern tip of Africa, proving false the view that had existed since Ptolemy that the Indian Ocean was land-locked. Simultaneously Pêro da Covilhã, traveling secretly overland, had reached Ethiopia, suggesting that a sea route to the Indies would soon be forthcoming.”

And all that had happened before 1492!

Once Ferdinand and Isabella captured Granada that year, and almost simultaneously sent Columbus’s expedition across the Atlantic, Spain and Portugal realized they needed to reach agreement on how to divide up the spoils of trans-oceanic imperial rapine. They did that in 1494, in the seminal Treaty of Tordesillas, which divided all the newly-discovered lands outside Europe between the two powers along a meridian line described as lying “370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands.” That line was about halfway between the Cape Verde islands (already held by Portugal) and the islands reached by Columbus, which are today’s Cuba and Hispaniola.

Under Tordesillas, the lands to the east of the line could be seized, settled, and used by Portugal and the lands to its west, by Castile/Spain. (The other side of the world would later be similarly divided between the two powers, in the 1529 Treaty of Zaragoza.)

One of the consequences of Tordesillas was that Spain had no direct access to the lands of West Africa which proved such productive “slave-harvesting grounds” for the Portuguese and the numerous other– generally non-Catholic– European powers that emerged, and that all became heavily invested in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Spain did have access to the mineral wealth– gold and silver– of the former Aztec and Inca Empires, and to the (usually forced) labor of the Native peoples of those areas. Spanish settlers in the New World could, and did, also buy enslaved persons from Portuguese, English, Dutch, or French slave-traders. They just couldn’t seize them directly from Africa itself.

… Then, in 1497, the Portuguese captain Vasco da Gama set out from Portugal, rounded the Cape of Good Hope, picked up a local pilot in East Africa, and continued under his guidance to Calicut in south-western India, which he reached in 1498. In 1500, another Portuguese captain made landfall in Brazil, immediately claiming it for Lisbon. However, most Portuguese adventurers remained more heavily focused on the fabled– and until then, Muslim-dominated– “spice routes” of the Indian Ocean, and the twenty years following 1500 saw the establishment of more than two dozen Portuguese trading posts ringing the entire Indian Ocean and pushing deep into present-day Indonesia and up the eastern coast of China.

I am not embarrassed to note here that the main source I’ve been using for the above has been Wikipedia. I realize Wikipedia is far from infallible, and in some areas of current concern has some notable editorial biases. But for these historical materials, I have found the Wikipedia entries really helpful.

As this project progresses, I’m expecting to be using a much wider range of sources, including many of the books and other materials I’ve been gathering and diving into over the past year.

Wikipedia is also fabulous for pictorial sources!

Finally, I’d like to invite any interested persons to help this project by contributing materials to this project of constructing a year-by-year, world-surveying chronology. My sense is that there are large parts of the world I know little about and that get short shrift in Wikipedia and the other sources I’ll be using. So if you’re able to send in chronological entries for, say, East Asia, South America, Central Asia, or whatever– or if you’d like to contribute short, multi-year summaries of developments in some area you’re familiar with, that can be slotted into the general chronological theme as we go along, then please drop me a line!