Within just 100 days, the Covid-19 pandemic has significantly shifted the balance of power in the global system from the United States toward China– and this trend looks set to continue, or accelerate, over the coming months and years.

This is the case not just because U.S. deaths and death-rates from this virus (currently 71,152 total reported deaths, or 21.78 per 100,000 of population) are considerably greater than China’s (currently 4,663 total deaths, or 0.33 per 100,000), but for a number of other reasons, too. Key among them are:

- the criminal ineptitude of the U.S. government’s response to the pandemic, which has led to the current situation in which the virus is nowhere close to contained but continues to spread nationwide– whereas China succeeded in containing the virus by the end of March and is now cautiously reopening its economy;

- the deep weaknesses in the United States’ heavily free-market-skewed and military-obsessed economy and society which had already, before Covid-19’s arrival led to the decay of the country’s public-health infrastructure and the non-existence (or chronic atrophying) of the social safety net– whereas China had learned from the SARS epidemic of 2002 to keep ready its already-robust public-health infrastructure and was able speedily to deploy quarantining, testing, and other safety measures nationwide.

There is, as I noted here recently, a definite temporal element to the current coronavirus crisis. Once the Chinese leadership grasped the scale of the challenge, they took broad and effective measures to contain and then eliminate the virus. Vijay Prashad, Du Xiaojun, and Weiyan Zhu wrote an excellent description of how this was done. (It has some beautiful illustrations, painted by Li Zhong– here, and above.) Some of the most interesting portions of that lengthy account cover the first three weeks of January:

There is, as I noted here recently, a definite temporal element to the current coronavirus crisis. Once the Chinese leadership grasped the scale of the challenge, they took broad and effective measures to contain and then eliminate the virus. Vijay Prashad, Du Xiaojun, and Weiyan Zhu wrote an excellent description of how this was done. (It has some beautiful illustrations, painted by Li Zhong– here, and above.) Some of the most interesting portions of that lengthy account cover the first three weeks of January:

In the early days of January 2020, the National Health Commission (NHC) and the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began to establish protocols to deal with the diagnosis, treatment, and laboratory testing of what was then considered a ‘viral pneumonia of unknown cause’. A treatment manual was produced by the NHC and health departments in Hubei Province and sent to all medical institutions in Wuhan City on 4 January; city-wide training was conducted that same day. By 7 January, China’s CDC isolated the first novel coronavirus strain, and three days later, the Wuhan Institute of Virology (Chinese Academy of Sciences) and others developed testing kits.

By the second week of January, more was known about the nature of the virus, and so a plan began to take shape to contain it. On 13 January, the NHC instructed Wuhan City authorities to begin temperature checks at ports and stations and to reduce public gatherings. The next day, the NHC held a national teleconference that alerted all of China to the infectious novel coronavirus strain and announced the need to prepare for a public health emergency. On 17 January, the NHC sent seven inspection teams to China’s provinces to train public health officials about the virus, and on 19 January the NHC distributed nucleic acid reagents for test kits to China’s many health departments. Zhong Nanshan – former president of the Chinese Medical Association – led a high-level team to Wuhan City to carry out inspections on 18 and 19 January.

Over the next few days, the NHC began to understand how the virus was transmitted and how this transmission could be halted. Between 15 January and 3 March, the NHC published seven editions of its guidelines. A look at them shows a precise development of its knowledge about the virus and its plans for mitigation; these included new methods for treatment, including the use of ribavirin and a combination of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and modern medicine. The National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine would eventually report that 90 percent of patients received a traditional medicine, which was found to be effective in 90 percent of them.

By 22 January, it had become clear that transport in and out of Wuhan had to be restricted. That day, the State Council Information Office urged people not to go to Wuhan, and the next day the city was essentially shut down. The grim reality of the virus had by now become clear to everyone…

For those of us living in the United States, it is poignant indeed to learn of the breadth, organizational acumen, and effectiveness of the steps taken by the Chinese government and contrast them with the denialism, xenophobia, cronyism, anti-scientific bias, chaos, and sheer mean-spiritedness that have marked our President’s actions.

* * *

Traditional measures of the “strength” of a nation look at either its military capabilities or its economic achievement. It is clear, though, that other factors also critically undergird a nation’s strength. The first is a country’s internal social cohesiveness, which itself derives from a number of hard-to-measure factors– though nearly all of them are related in some way to the degree of trust that exists within the society: both the trust that exists among the society’s different members and groups and the trust they have in their institutions. The other two “soft-power” determinants of a country’s strength are the network of constructive relationships it enjoys with other countries and the general prestige or standing that it enjoys among people worldwide.

Since his arrival in office, Pres. Trump has seriously degraded all of these measures of the United States’ “soft” power, though it is also true to say that the level of the country’s internal social cohesiveness has been low for several decades– that is, the decades in which a hyper-individualistic and money-worshipping ethos has taken hold.

Trump and the financier-dominated circles in which he likes to move have been focused tightly on the need to get “the economy” moving again– even if, as he acknowledged yesterday, this could come at the cost of the lives of numerous Americans. By “economy”, he clearly means corporate profits though (following Umair Haque) it is always useful to remember what the true roots and origins of a weighty word like this one are. “Economy” comes from the two Greek words “oikos” (a home) and “nomos” (a body of laws or or principles.) Hence, a country’s “economy” is– or should be– a set of principles that govern the good stewardship of the nation’s “household”, that is, the resources at its command– including, of course, the human resources that constitute it.

A country’s “economy” is not synonymous with the corporate profits that its shareholders and financiers can pull in. And certainly, a country’s “economy” should not and cannot be placed in any type of zero-sum opposition to the wellbeing of its citizens.

If Americans are all dead, who will buy the products of the country’s corporations? Who will pay the taxes that let the shareholders of Raytheon get fat? Who will shine Steven Mnuchin’s shoes?

* * *

So, looking forward, we see a situation in which China and a number of other advanced countries that have contained and nearly eliminated the coronavirus, and have in place good mechanisms for preventing it from exploding once again, will be cautiously moving forward on opening up their societies and their economies on the basis of the new, epidemic-preventing measures they will be installing… while the United States (and Britain) will be spending the coming months still mired in the web of the virus and its demands.

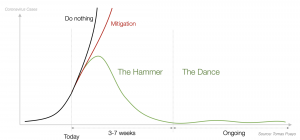

In Tomas Pueyo’s potent imagery of “The Hammer and the Dance”, the “dance” part of the United States’ experience of Covid will be bumpy and still have a very high mean level.

In Tomas Pueyo’s potent imagery of “The Hammer and the Dance”, the “dance” part of the United States’ experience of Covid will be bumpy and still have a very high mean level.

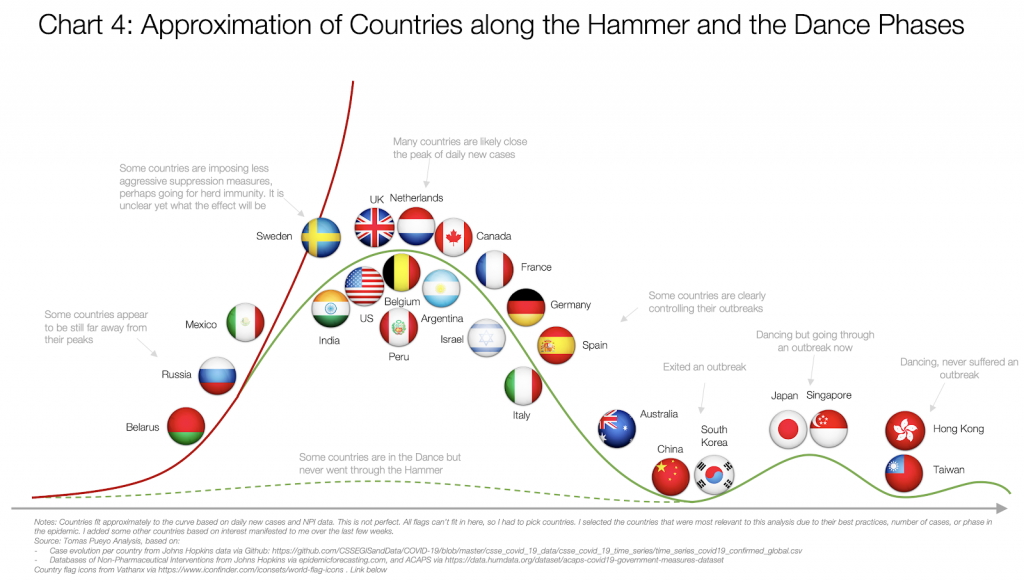

And this, for what it’s worth, is where Pueyo placed the major nations of the world on the “hammer/dance” curve as of April 20:

The countries that are “dancing low” on this curve will evidently be able to restart their economies sooner and more effectively.

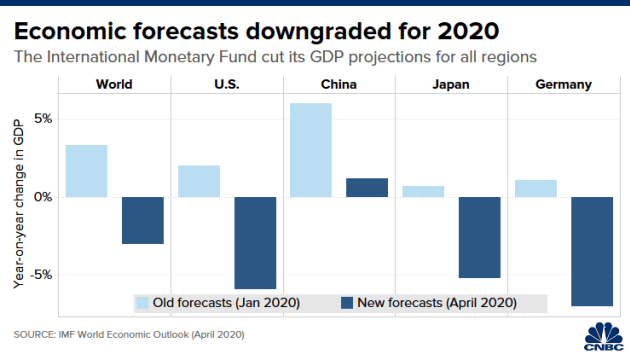

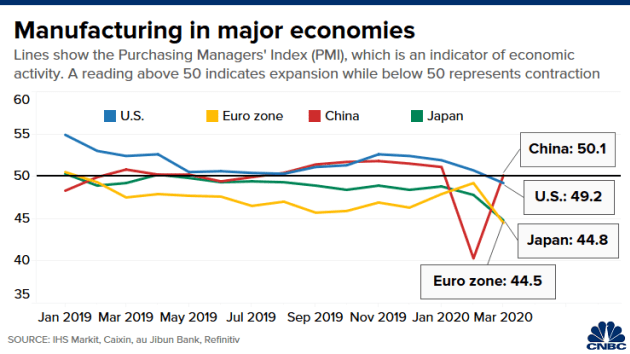

On April 24, MSNBC published a series of charts showing both what the measured economic effects of the pandemic had been on various countries’ economies, and some projections. (Since then, the situation has almost certainly gotten worse for the United States.) Here are two of the charts:

* * *

I have a lot more to write about about the rapid dissolving that the United States’ previous position of global hegemony has been undergoing in the past 100 days. But this is a start…